To celebrate this month’s music issue, we’re posting a piece written by Joseph Bien-Kahn on San Francisco Jazz trombonist, Danny Grewen.

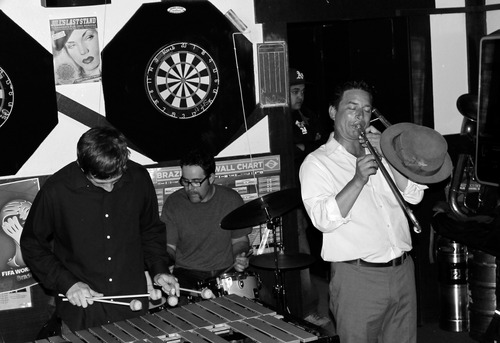

Even dressed up, Danny Grewen is a little disheveled—in a pinstriped suit, a polyester button-down with the collar open, and a fedora he’s still all herks and jerks. Grewen is lugging around a taped-up trombone and a messenger bag open and overflowing with tape recorders, loose wires, and microphones when I interview him. He has a head of curly black hair and boyish good looks that clearly serve him well. But the thing that strikes you most about Grewen are his hands—they are strong and calloused and cracked; the hands of a blue-collared worker. The stereotype of the coddled artist continues to persist, but in today’s San Francisco, if you want to play jazz and pay rent, you have to work.

I met Grewen at Trouble Coffee in the Outer Sunset. Every once in a while he’d say something too sharp and a little too dark when talking about the city, and then burst out into untended laughter. He talks the way he moves, quick spurts with long breaths, a mischievous grin peeking out of his stubbly jaw. He kept his bag over his shoulder and recorded the interview on an ancient tape recorder he’d found at the corner of 45th and Kirkham for his own records. Grewen’s well loved in the neighborhood—at the coffee shop and later at the Flanahan’s Pub a few blocks down, everybody knew his name. But because of a jump in rent, he’ll soon be forced to move.

It hardly needs restating that San Francisco’s rents are rising at an alarming rate. According to a November 2013 article in the New York Times, the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment is a staggering $3,250, the highest price in the nation. Only 14 percent of homes are accessible to middle-class buyers.

The city is changing which is what cities do. But it means it’s becoming harder and harder to be a musician in San Francisco, especially a jazz trombonist. It’s nearly impossible for Grewen—who grew up in the Richmond, San Francisco’s sleepy northwestern district by the beach, with his mom (also a musician), and attended the School of the Arts—to stay. Now he’s crashing on couches, looking for something affordable in the most expensive renters’ market in the nation.

He left the city once, briefly, to play jazz on cruise ships—“Well, that’s not really jazz is it?”—but has spent the last fifteen years gigging around San Francisco. It’s been a long time since music was lucrative here, but Grewen has made a fine living playing jazz trombone. But now, at 36, his steady gigs are disappearing. He says the jazz scene was “happening” in the late 90s, right when he came back to the city: “Bruno’s was a great club. It’s still there, but if you remember what it was like, it was a beautiful place. There was even two bands going in one night—one in one room and then that one would stop and the band would start in the other room.” Bruno’s no longer hosts jazz performances, according to its website: “Every week, we present a brilliant line up of entertainment featuring a collection of the Bay Area’s finest DJ’s spinning an eclectic mix of party jams and dance music.” If you want to run a club in San Francisco, hip-hop and house music are the way to go. Jazz just doesn’t fill a room in today’s city music scene. Grewen says he doesn’t want people to go see jazz because it’s something they ought to do—he wishes people would get excited about it again. He doesn’t think it should feel “like your supporting a relative that’s down on their luck or something; it’s fun music.”

Grewen told me he’s seen a lot of San Francisco’s jazz musicians move away—some to the East Bay and many to New Orleans. The problem is, when a city becomes too expensive for musicians, it changes its character. The success of eccentrics like Grewen was one of things that gave San Francisco its flavor. “You want to try to hold onto the things that made great cities great,” Randall Kline, the founder and executive artistic director of SFJazz, explained. “What was great about this city, San Francisco, was this whole creative class—people who lived here who were not just musicians, there were tons of artists, actors, it was just a vibrant scene. Now there’s a lot less of that per capita then there was.”

Kline moved to the city in the 70s to try to make it as a musician, which was difficult, even then. But rent was cheap—he remembered paying $100 for a room in Bernal Heights—which made San Francisco a good place for lots of young musicians and artists to live and work. Instead of playing for a living, Kline applied for a $10,000 grant from San Francisco’s Hotel Tax Fund, which he used to start “Jazz in the City”—a two-day showcase of local artists—in 1983. The festival, which would eventually become the San Francisco Jazz Festival, was “kind of a bust” that first year. But Kline continued to improve it, and by the third year it started to gain some momentum. At that moment, the jazz scene was moving more towards festivals and institutions, and there was “lots of talk about jazz as America’s classical music”—and therefore warranting the same governmental patronage. Kline began to work on turning the festival into a more permanent jazz non-profit.

In 2000, the organization officially became SFJAZZ, which in turn led to an expansion of the educational programs offered by the non-profit, an extension of the performing season, and the creation of the SFJAZZ Collective, a kind of institutional house band, which has an impressive, annually-rotating line-up that releases records and plays many live shows. Right around that time, Kline also began to dream of building a venue that could house the institution and offer a consistently high-quality product to the city’s jazz enthusiasts. A decade later, in January 2013, the state-of-the-art SFJAZZ Center opened to the public.

The venue—which cost $64 million to construct—was definitely a gamble. But Kline explained that “we wouldn’t have done it if we didn’t think there was a market.” Instead of trying to follow the jazz club model—which has failed for San Francisco institutions like Bruno’s and Jazz at Pearl’s—SFJAZZ is a non-profit presenter, like the symphony, the ballet or the opera. Because of that, there is less pressure to sell out every show and bend to market forces. Instead, Kline hopes to use the venue as a tool for teaching and growing the San Francisco jazz fan-base. And the gamble is paying off. “When we broke ground for this place, we had 3,000 members—student membership is about $60, some people give six-figures, a lot of money to support what happens here—and that number grew to 4,500 on opening night, and it’s just under 10,000 now,” he said. “That’s a promising sign about community acceptance.”

Kline hopes that the growing fan base will mean more business for jazz clubs all around the city. “We’re doing a lot more with local acts now, and as we get settled we’ll do even more with local artists, which will hopefully encourage more scenes in other places that can do well too,” he said. “But people need to be there first.” So this is the odd pose in which the San Francisco jazz scene currently stands—it can support a $64 million venue, but cannot support a local player’s rent.

Michael Bailey was hired by Bill Graham 26 years ago and has been booking bands to play at the Fillmore Auditorium ever since. “If there were jazz artists that were selling 5,000 tickets, there would be more venues presenting that business,” he said. The Fillmore has been a central setting in the San Francisco music scene since Graham organized his first concert there in 1965. Jimi Hendrix, The Doors, Janis Joplin and many others made it a legendary venue in the late 60s, and it soon became a mandatory stop on any contemporary rock group’s West Coast tour.

But the opening of the auditorium did not mark the inception of the Fillmore District as San Francisco’s music neighborhood. In the 40s, the Fillmore was home to a large, African-American middle class and the district, dubbed “the Harlem of the West,” was world famous for its jazz clubs. Elizabeth Pepin and Lewis Watts’ wonderful Harlem of the West: The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era chronicles the heyday of the Fillmore through pictures of and interviews with those that witnessed the scene. The old club names still resonate with city jazz fans—The Champagne Supper Club, The Primalon Ballroom, Bop City—and the acts that frequented the neighborhood can be appreciated by anyone. Ella Fitzgerald, Charlie Parker, and Louis Armstrong would all just pop by and play a set for the loyal Fillmore crowds. “You’d see famous people all dressed up walking around the Fillmore all the time,” musician and educator F. Allen Smith said in the book, “I saw Duke Ellington in the Fillmore. Miles Davis in the Fillmore. Dizzy Gillespie was in the Fillmore. You name them, they were there.”

“There was an audience—a lot of this comes down to audience—and there was an audience for that kind of music,” Kline said. “It generally doesn’t work the other way around, if you build it they will come. It happened naturally around that time.” But that loyal jazz audience was unceremoniously done away with by city officials. In 1948, the city declared the heavily black district “blighted” under the California Redevelopment Act of 1945, which gave it the authority and federal funding to reconstruct and redevelop the neighborhood. Over the next few decades, through the use of eminent domain, the Fillmore was leveled—4,729 businesses forced to close, 2,500 households told to leave, and 883 Victorian houses destroyed—and rebuilt as what it is today.

“Now it’s mostly public housing projects or mixed-use projects and it doesn’t feel like a neighborhood anymore,” Kline explained. “And there’s very little black middle class living in San Francisco at all right now, never mind that neighborhood.” And along with the neighborhood went the city’s most loyal jazz audience.

Obviously, the cranes are back again, building high-rise apartments in the Mission and South of Market. Those neighborhoods were places where young artists could live and create in the city as recently as five years ago. Now, they are some of the trendiest and most expensive in San Francisco. The Fillmore District itself is now surrounded by Pacific Heights, NOPA and Hayes Valley, three of the city’s most affluent neighborhoods. But the rent hikes are not localized to one part of the city. Even at the western edge of town, where the sun rarely breaks through the thick sea fog, landlords are asking for hundreds more per month than just a few years back. Which is why Grewen found himself at the Eviction Defense Coalition a few days before I spoke with him.

In the middle of a sentence about his favorite gigs in the city, Grewen stopped suddenly and started digging around his messenger bag. He pulled a battered Macbook from under a mess of tape recorders and wires, and opened and balanced it upon the parklet bench. “I got some movies, you wanna see them,” he asked me, cueing one up before I could answer, “I’m making little jazz movies, you know?”

The picture on the screen was ominous, light cutting sideways across a deserted hallway of a high rise. “So I was leaving the Defense Coalition and I started to walk down the stairs and I saw an empty floor and I was like, oh, this looks really nice,” he said. “It’s almost like a Hitchcock movie. It’s almost like looking into a painting.” The video started and I watched Grewen, dressed in the same pinstriped suit, walk slowly down the hallway playing his trombone. About two-thirds of the way down, he starts to leave focus and the music grows quieter—the scene takes on a dream-like state. But then gradually, he returns to the frame, and the music and the image become crisp again. And then he’s right in front of the screen, playing his trombone, five stories above San Francisco.

He shut the computer, put it back into his messenger bag and lit a cigarette. I asked him if he was bitter that he missed the heyday of San Francisco jazz. “It’s just far back enough that I don’t really hear a lot of stories about Bop City or Jimbo’s or anything,” he said. He told me he has met a few of the “original daddios” though, and the ones who are still around still play well to this day. He loves to watch Nole Jukes at the Seahorse every Tuesday and John Coppola plays trumpet in the Green Street Mortuary Band. “I played that gig for about ten years or so,” Grewen said, chuckling. “It was steady.”