In this series five different writers talk to one writer about five (or more) of his different books. In this fourth interview, Hayden Bennett talks to Brian Evenson about A Collapse of Horses. Read the first interview with Colin Winnette, the second with Matt Bell, the third with Brian Conn, the fourth with Amina Cain.

Hayden Bennett in Conversation with Brian Evenson

To figure out this series, Brian Evenson and I had been corresponding for a few months, and he asked me if I wanted to talk about his not-yet-released collection, A Collapse of Horses. I read the book in one sitting in the basement of a bookstore and when I went out into the afternoon and down the street, I saw a subway grate and had to stop. For a reason not known to me, all I could do was look at the subway grate. Something about it scared me and looking at it evoked a physical memory of reading the stories. And whatever might actually be scary about subway grates and New York City transit aside, Evenson’s collection had done something, to me, it always does.

In the essay On the Short Story and Its Environs, Julio Cortázar writes about a certain kind of obsessive and fantastical story, and about, in its making, “the abominable clot that has to be worked out with words.” To work out the clot isn’t at all literary, Cortázar says, but is rather a transmission from a place where everything is decidedly foreign to the everyday self. Cortázar explains the effect of the story relies on the author’s ability to transfer an obsession to the reader, and gives her the impression that what she’s read has somehow arisen out of herself.

And that, I think, is the effect Brian Evenson’s work has always had on me: his best stories are able to possess in a way they seem to have posessed the author, and to read his work can be like picking up a signal from an unknown frequency, or discovering a new and strange room in your house.

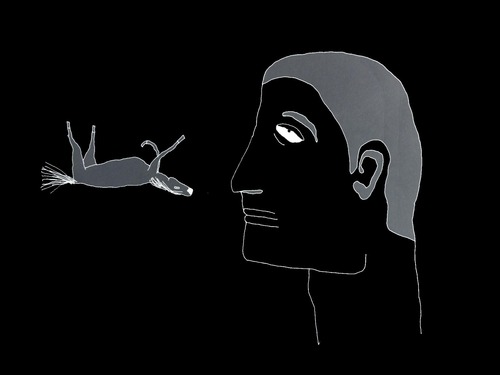

A Collapse of Horses stands with Evenson’s best work, and the book made me think of Cortázar’s essay because the stories evoke the sort of atmosphere that there’s no real way to analyze. The concern of the collection (which I think can be summed up in the title story: a man sees horses lying down and becomes obsessed with whether they’re asleep or dead) makes me think of Beckett. The fixed point of reality in many of these stories is liable to change, but in this collection, more than anywhere, Evenson always feels generous, human. The book has...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in