An Interview with Comics Artist Sacha Mardou

Sacha Mardou is a witty and literary comics artist whose work has recently been enjoying some positive attention. She’s also one of my favorite pen-pals. She and I met several years ago through our participation in zine publishing—a worldwide yet fairly teensy community—and we have kept up a lively letter correspondence, and collaborated on a few book projects, since then.

A British transplant to the American midwest, Mardou, who publishes under her last name, has put out self-published mini-comics about indie bands (Manhole #3), secret love affairs (Manhole #4), and Anaïs Nin’s personal life (Anaïs in Paris). Her books are often reminiscent of Adrian Tomine’s work because they are literary enough to function as stories without the art, but they’ve also got this incredible art.

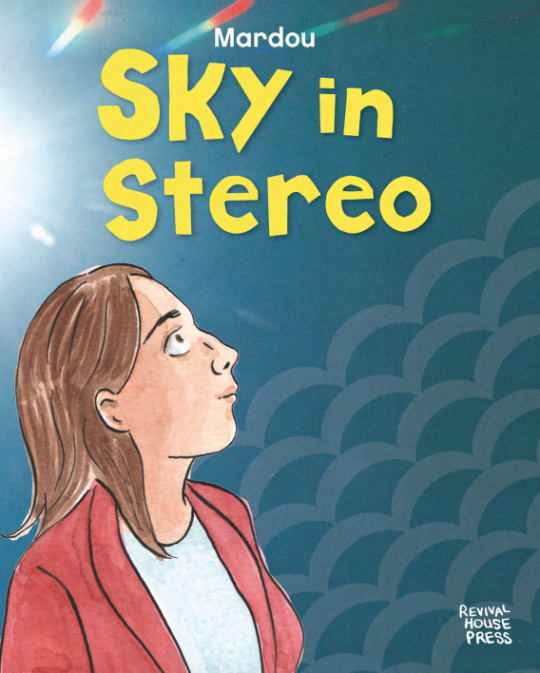

Her comic book series, The Sky in Stereo, might be the most important thing to know about Mardou at the moment. Set in the 90s, it looks, with eyes wide open, at the teenagers who are awkwardly—and sometimes, due to the increasing availability of heroin, dangerously—coming of age in Manchester’s thumping music scene. The series, now in its second issue, was nominated for the Ignatz award for Outstanding Series and named a “notable comic” by editor Scott McCloud in The Best American Comics 2014.

Mardou lives in St. Louis with her husband, the cartoonist Ted May, and their little girl, Veronica. As someone who has a lot of pen-pals, I can tell you: A letter from Mardou—almost always embellished with her expressive drawings—is the best kind of mail to receive.

—Katie Haegele

I. THERE’S A LARGER WORLD OF INDIFFERENCE, BUT SO WHAT?

THE BELIEVER: Recently you told me you’ve noticed a trend: Female comics artists in movies. There’s Phoebe Gloeckner’s graphic novel Diary of a Teenage Girl, which Marielle Heller made into a film, Regina Hall’s character in People, Places, Things, as well as the film you worked on. Is being a lady comics artist cooler than it used to be, or something?

SACHA MARDOU: It’s a thing to be now, a pursuit that it wasn’t when I was twenty-two. I couldn’t explain to my mother then that I seriously wanted to make comics for the rest of my life. You couldn’t go to school to study making graphic novels, so things have come a long way. And Alison Bechdel’s winning that MacArthur genius grant was a huge thing. It’s so great for her, and for comics to be validated like that.

It’s a weird time. The other end of the scale is that Comic Con and stuff are huge now, comics have been co-opted by the entertainment machine and apparently everyone I know was a big comics nerd all along. Who knew?

What I do still feels pretty marginalized, honestly.

BLVR: How so?

SM: In the wider world, who really knows or cares about small press comics?

Sky in Stereo was a breakthrough comic for me—it got really positive reviews, an Ignatz nomination, a screenwriter-director picked up a copy and it led to me drawing comics for a movie. Sometimes I get emails or postcards from people I haven’t met, telling me how the book struck a chord with them, or reminded them of their teenage years; that’s the best thing. I felt like such a dork as a teenager, out of step and unsure of myself. And now twenty years later, people tell me they felt exactly that way too and that I nailed it in my story.

On the other hand, I get invited to talk at Comic Con St. Louis and I’m surrounded by grown-ups dressed as Poison Ivy or the Eleventh Doctor Who. I sell maybe three books and the guy at the next table who’s selling his possibly litigious Justice League of America fan art has a healthy herd of fans and makes a ton of cash. This isn’t sour grapes! It’s sort of how things should be, really. It feels like not much has changed since my first self-published comic: I’d skulk into Forbidden Planet in Manchester, looking through the piles of superhero comics to see if any of my comics had sold. I only ever sold one copy. There’s a larger world of indifference, but so what? Mini-comics have changed my life. They found me true love and caused me to switch continents.

How is it to be a zine writer these days?

BLVR: It’s interesting—self-publishing is certainly a marginalized thing to do as a writer, but zines are apart from that. They have their own culture and history, and within that sphere there’s a thriving and supportive community. I mean, you and I met through zines, though I can’t remember now exactly how.

SM: We met because I bought [your zine] Things I’ve Lost / Things I’ve Found on a trip back home to Manchester. In a little booth in Afflecks, a sort of indie market emporium on three levels, your zine was on sale and I bought it and loved it. When I got home to the States I wrote you a snail mail letter and sent you a comic too, maybe it was Manhole #3?

BLVR: Oh yeah! The one with the story about the two girls who meet at a rock show. You’re writing the script for a graphic novel now, also about a band, only it’s set in America, right? Are the characters in the story English?

SM: It’s about a British indie band set in 1994-95. Before everyone had cell phones or cared about the internet. That’s an important factor.

They do come to America and ultimately fail to make anyone care about them here. I really don’t want to talk about it too much as I’m still in the writing stage and its shell hasn’t set yet, if you know what I mean.

BLVR: I find myself thinking about the time before the internet a lot too—in terms of being a fan of music in particular, actually. I remember when it required some work, having to wait until your favorite magazine came out to read the interviews, or hoping the new album would include the lyrics, or else you might never figure out what the singer was saying.

SM: And listening to radio charts on Sunday afternoon with my finger hovering over the “record” button. I used to buy the NME in my teen years, and before that, Smash Hits, which was a great teeny bop magazine in the UK. The journalists were really sharp and funny. I had a letter printed in Smash Hits! Adolescent triumph.

BLVR: Music is a recurring theme in your work—the character in The Sky in Stereo, for instance, is so tied up in following bands and going to shows. What is it about music that’s important to you?

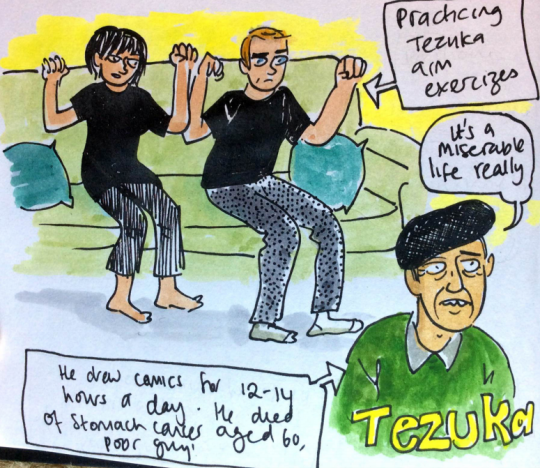

MARDOU: When I was writing the last chapters of The Sky in Stereo, there was a Nick Cave song I listened to over and over. It was like fuel. The song, “Albert Goes West,” has nothing to do with my work, lyrically. But it was such a powerful trigger. Listening to it without fail would get my itch to write started and it propelled me to the finish line. That’s just one example. I often appropriate song titles or lyrics for my story titles. Sky in Stereo might be my first-ever original title.

I discovered comics because of music. Deadline, this magazine that came out in the early 90s, had bands on the cover, drawn by Jamie Hewlett. I bought it for the bands but became obsessed by the comics inside, Hewlett’s Tank Girl and Nick Abadzis’ Hugo Tate especially.

BLVR: Jamie Hewlett! We love him in this household because we’re great fans of Gorillaz. Did you begin drawing comics at that time?

SM: Jamie Hewlett would draw all the covers for The Senseless Things, a band I wasn’t really into, but I bought a few for the covers. He wanted to be like the artist who did all the Yes album covers, I remember reading, so the Gorillaz project fit with my idea of him.

I was sixteen or seventeen when Deadline was coming out and I did try drawing my first comic then and discovered how hard it was to do a comic—like it seems like it should be easy as they’re so easy to read! My first attempt making comics was around the time of riot grrrl. A friend was making a feminist zine and I promised a comic for it, a Tank Girl rip-off thing. I gave up pretty quickly but came back to it when I was twenty-two and finishing university.

BLVR: Did you begin publishing your own comics or zines at that time?

SM: My cooler friend gave me copies of [Peter Bagge’s] Hate and [Dan Clowes’] Eightball and something just clicked. I remembered that I totally wanted to make comics and so I did. I made a mini-comic photocopied from sketchbook pages, and didn’t even try to sell it. I just mailed it to people that I admired, like Clowes and Ian Svenonius, who was in the band The Make Up at the time (my favorite band ever). And those two both wrote back nice words of encouragement. It was sort of amazing to me.

I made a bunch of mini-comics called Stiro, short funny stories that my friend Fortenski wrote. Then I started to write my own stories and put them in a solo comic called Manhole, which I thought was a cool title but everyone thought was dirty sounding. In my mind it was like, the manhole is an entrance to a subterranean other-city full of sludge and dishwater, but nah, people just thought of butts!

II. THE SPIGOT TO THE INNER SELF

BLVR: One of the things I find most compelling about your work is how vast and varied your literary references are. Do you think of yourself as a writer who can draw, or an artist who can write? Or is that a totally faulty way of thinking about what it means to create comics?

SM: I studied English literature at college, and I’m glad of that. I do feel a bit out of sync with many cartoonists who have an art school background—an inferiority complex even? So yup, I feel more affinity with the writing side, but then, drawing is such a big part of my writing process. I always write first drafts in longhand and can’t go more than a page or two without scrawling illustrations amongst the text. It’s just more efficient and fun.

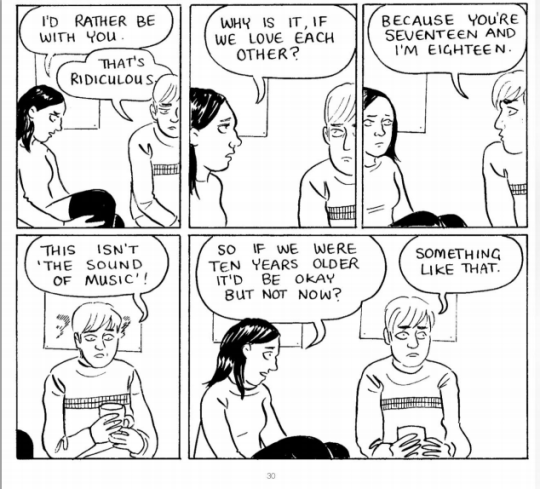

I was actually into drama for a while at school. The theory side of it anyway, Stanislavski and Brecht, that sort of thing. The “acting” in comics is such an overlooked aspect of cartooning. And that’s something I hope I express well, even though I’m not the most polished illustrator in the world.

BLVR: What do you mean by acting?

SM: It’s like you’re using your drawing ability to make people act and talk and you have to kind of get into it to be able to draw it. I can think of some examples in my head of comics that are quite popular, where the characters talk and gesticulate wildly and completely overreact physically. Like over-the-top body language. I wonder, when I see overacting in comics, if people are learning about writing from watching TV. You know? Everything’s so much larger than life in TV shows.

I think Dan Clowes is a masterful example of good acting in comics. Ghost World is panel after panel of perfect expressions and body language.

BLVR: Ah, I see what you mean. I admire the way your characters are more reserved. You can say so much more that way, ironically, don’t you think? It could be a cultural thing to an extent too—that famous British understatement vs. American exuberance.

SM: British understatement, yes. A good example would be the original BBC version of “The Office” compared to the sitcom it became in the U.S. It’s not a criticism, it was just so different. I think “30 Rock” was maybe the best and cleverest sitcom ever made, and it’s very American. Couldn’t have been a British show.

BLVR: Could you talk about The Strumpet and your involvement with it?

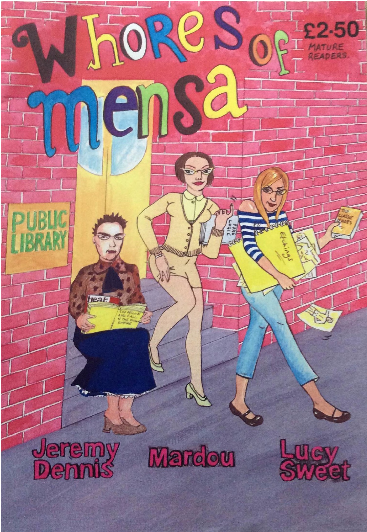

SM: The Strumpet has very little to do with me, except its origin. I came up with an anthology called Whores of Mensa in 2004. It was three women cartoonists with 10 pages each to do something vaguely related to literature. Lucy Sweet, who’s now a fantastic novelist and journalist in Glasgow, Jeremy Day (née Dennis) who’s an amazing cartoonist and artist. And me. It was my book just because I sort of bullied them into doing it. Before Issue Four came out we got legally challenged by Mensa, as it was apparently too confusing for potential Mensans: Wait, they have whores now?! It was so silly as we stole the name from a Woody Allen story (“The Whore of Mensa”), a fact that seemed to have escaped them. Anyway, a nice lawyer from the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund wrote a letter defending us and Mensa backed down, and we didn’t have to spend any money or anything.

By then I was sort of done putting anthologies together and wanted to focus on my work, so I handed the reins to Ellen and she evolved it into The Strumpet. She’s doing an amazing job. I love the book. It’s got a much bigger scope than Whores of Mensa.

BLVR: Who did the art?

SM: We drew each other. That’s Jeremy drawing me, me drawing Lucy and Lucy drawing Jeremy. Sorta. It’s kind of a hilarious portrait of Jeremy. She’s much cuter / more stylish in real life.

BLVR: You said something to me not long ago about coming to terms with the kind of artist you are—not someone who is fussy with visual details, was your example I think—which I guess is a way of saying you’ve found your voice. Does that take most people a long time, do you think?

SM: I think coming to terms with my style is more on point. Visual details are important to me but I’m comfortable with how I draw now, my sketchbook-y look. That self-acceptance took a long time.

I remember reading a quote by Neil Diamond, talking about song writing. He called it his spigot to his inner self. I love that! Who says spigot? But I get his meaning. I’ve discovered that if I create the right conditions and show up regularly at my writing desk, the story shows up too. And I think about the writers I love and how they became masters of the form in their fifties (usually). It’s made me excited for middle age. Bring it on!