An Interview with Poet Lucy Ives

While Lucy Ives went out for a snack, I lay down on the couch, first checking my phone, then reading the first five pages of Susan Howe’s Sorting Facts: or, Nineteen Ways of Looking at Marker, in which she calls poetry “factual telepathy.” Howe sees poetics as a way of conjuring facts, that history isn’t the product of reliable sources, but a process of posing events, batting them around, dressing paper dolls in fact costumes, dragging an information magnet through the streets.

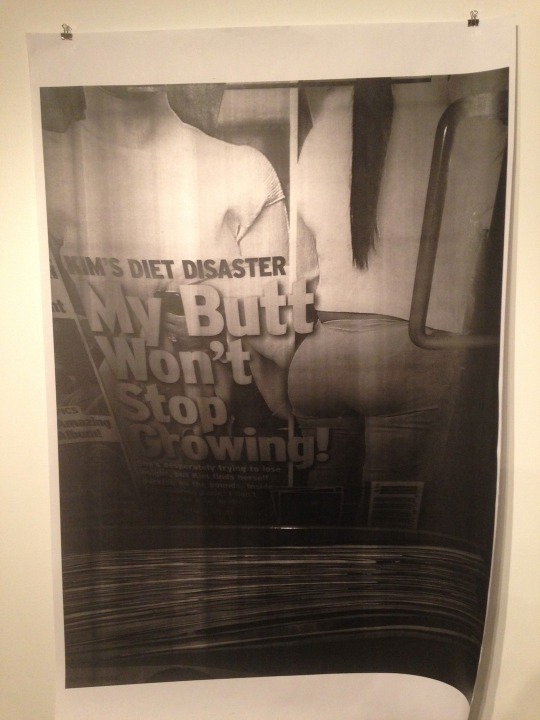

Ives had just finished teaching a companion class to her latest project and installation, Real Allegory, which ran this spring at Flying Object, in which she attempted to call into question commonplace distinctions between historical and literary description and interpretation. Below you’ll find a document of and about a ‘real’ historical event, a conversation between Ives and me on an April evening that became an audio recording, then a transcription, then an edited transcription, in which I chose what I deemed to be the ‘significant’ moments, in which I spruced up all the times I sounded like an idiot. Does this mean the facts are lost? Did I trace over the facts? The historical record inevitably rewrites the world, willingly or unwillingly imitating it, splintering it into fabrications, each one a script for multiple potential reenactments.

— Patrick Gaughan

I. YOU CAN SPEND ALL OF YOUR TIME IMITATING THE WORLD

PATRICK GAUGHAN: I was reading Tropics of Discourse this morning per your recommendation and could see why you were into it: Hayden White’s ideas of historical narrative as being composed of metaphor and other literary tropes, as opposed to successions of facts.

LUCY IVES: I think he’s coming out of a poetics tradition, and that’s a key term in my project: poetics. I wanted to be able to think about poetics outside of literary texts, to see if literary logic could exist in other kinds of environments. “Narrative” and “Description” can be literary, but they don’t have to be. I wanted to understand, “What would a non-literary poetics be?” Because I think when we talk about poetics, that’s actually what we mean. Or when you use that term, you mean something that isn’t exclusively literary. Sure, there’s poetry and there are certain conventions associated with it, but the notion of poetics can exist outside of a literary space.

PG: So you’re saying that literary tropes and styles are linked to not only art but also history?

LI: I think White’s enabled me to find ways to consider this idea. I’ll be in conversation with someone who isn’t a writer, let’s say a photographer, and...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in