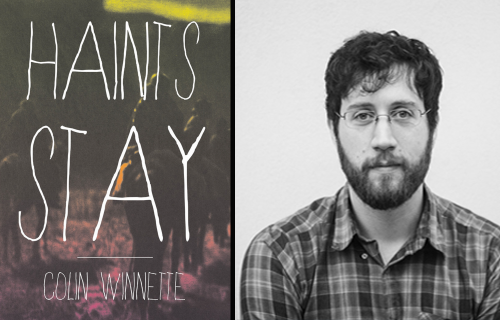

Author photo by Jennifer Yin.

Karolina Waclawiak in Conversation with Colin Winnette

Colin Winnette’s Haints Stay is a superb, sweeping western full of ghosts looking for a place to land. Winnette escapes easy classification with his fifth book, building a world that falls somewhere between Jodorowsky’s El Topo and Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, while rearing a singularly haunting bastard child all his own. We sat down at Skylight Books in Los Angeles, in front of an audience, to talk about Winnette’s take on traditional westerns, how his childhood in Texas influenced him, and just what his unforgettable characters are looking for.

—Karolina Waclawiak

I. SOMEWHERE ON THE HORIZON

KAROLINA WACLAWIAK: Your book was labeled an “acid western,” was that an intention of yours, or was it a marketing thing?

COLIN WINNETTE: It was a marketing thing. I mean, I think it’s a descriptive label, and useful, but I was really hesitant around the idea of even calling it a Western. While it’s definitely very interested in and dependent on westerns, there are so many parts of “The Western” that this book just completely throws away, or looks at very obliquely. I really just plucked out the parts of The Western that I was interested in fucking around with. And I guess it’s a kind of trippy book…

KW: Have you ever done acid?

CW: I’ve never been clear on how it works about publicly speaking about taking drugs…

KW: It’s fine.

CW: Alright. I’ve taken acid. I didn’t particularly like it. I’ve taken other hallucinogens that I liked much more. Acid was very, uh, it was too lucid of a trip for me. Even though I was seeing all this crazy shit I was like, ah, man, you’re just on acid. I want to forget that I’m on a drug, which is why alcohol is sort of preferred.

KW: That’s funny because I only took acid once as well, and it was horrible. And I kept saying, ‘When am I going to stop being on acid?’

CW: That’s the other thing. It lasts for fucking ever.

KW: Yeah, it was like three days, and I had to take an airplane.

CW: Three days?!

KW: It felt like three days. But it triggered long-lasting anxiety attacks, so it was really like ten years or maybe forever. I was at a rave in Oakland. On Halloween.

CW: Were you taking acid all throughout the night?

KW: I was candy-flipping.

CW: I have no idea what that is.

KW: That’s taking acid, a liquid acid, and ecstasy. And then I had to fly home to LA still tripping. It was horrible.

CW: Did the ecstasy level it out at all?

KW: No. Not at all. I was probably dinner party conversation for years for the person who had to sit next to me, as the worst person he had ever met.

CW: Do you remember any particular thing you said to the man?

KW: I just kept asking him if we were going to die.

CW: Oh, I do that regardless of whether or not I’m on acid and ecstasy.

KW: Weaving into the death question actually, I really loved the desert backdrop in Haints Stay, and I was curious what you thought about what the desert has that makes it the perfect backdrop to a struggle for freedom and life itself?

CW: Well, I mean, it’s very hard to survive in the desert. I think struggle is just part of it. We’ve all spent some time there, so we have a sense of what it’s like. But very few of us have actually been trapped there. Everybody who winds up in the desert in Haints Stay is trapped there for one reason or another. So, first they have to figure out how to survive. But then, once they’ve figured that part out, it’s like… alright, I’ve figured out how to survive… Now what? I have my mind and the sun and the heat, and…

KW: And hopefully a town somewhere on the horizon.

CW: And maybe potentially a town somewhere on the horizon. There’s always that hope, that dream of getting somewhere. Although when Brooke’s in the desert, he just keeps zigging and zagging and deciding he’s going to die then deciding he’s not going to die. But, you know, there’s other characters doing shit while that’s happening.

KW: Everyone’s trapped but everyone’s excited to kill.

CW: Excited? Did you feel like they were excited?

KW: I’m just joking. It’s not an excited to kill, but there’s this ongoing struggle for survival and whoever’s in the way of that quest for survival, you know, has to be eradicated.

CW: When I wrote this book I was like, yeah there’s some violent scenes, whatever, but mainly it’s about these people trying to get by, trying to love each other in their own ways and figure out a way to live, and the things that get in their way of doing so. Then we did this book launch in San Francisco where thirteen people read sections of the book and retold what they remembered. And most of what people remembered went something like, “Well, a shitload of people died, and one main character gets murdered gruesomely by someone they cared about, and then, uhh next.”

KW: No!

CW: Yeah. I was just like, holy god, what have I done?

KW: I mean, people bake bread, there’s a baby born…

CW: Definitely some bread baking. Definitely a baby.

KW: There’s a lot of wonderful things that happen in this book.

CW: Thank you.

KW: I found it very heartwarming at the end, actually. I felt there was violence, but I actually left the book with a feeling of hope, which I thought was interesting. It didn’t feel bleak to me at all. I was putting myself in the shoes of your characters, and thinking like, how would I survive? How would I survive a snowstorm, how would I survive an empty town? Who would I end up with if there was a town full of bandits and I knew I had to survive? So, it’s a very hopeful book.

CW: Yeah!

II. DENTON, TEXAS

KW: You grew up in Texas, right? How do you think growing up in Texas informed the kind of stories you tell? I was really excited about this book because it’s not about the East Coast or the West Coast. I think you were writing about a time period and a world that I don’t see in novels that often in contemporary fiction.

CW: I grew up in a town called Denton, Texas, which is a small town but it’s not like a “Texas small town.” It’s really a college town. So there’s a lot of Texan things about it, but it’s not, you know I wasn’t in deep Texas Texas, whatever that means. But, I grew up with a lot of sky. A lot of room. A lot of heat. A sense of everything being far away. There weren’t corner stores. You walked a mile to the Piggly Wiggly. And if you wanted to see anything other than Josie and the Pussycats (again), you drove an hour to Dallas to go to the Angelika Theater. Growing up in Texas probably influenced how ludicrous some of the “western stuff” in the book is, because everything I grew up around was just so funny to see, like a two year old dressed up as a cowboy eating ice cream on his way to see Transformers. A lot of the humor in the book comes from messing around with some of the things most Westerns take very seriously.

KW: Did you watch a lot of Westerns growing up? And what were you reading? I feel like this book is a challenge to that American-ness of Westerns.

CW: I definitely watched a lot more and read a lot more when working on the book than I did as a kid. But, growing up, it was just sewn into everything in a way that felt very normal at the time, but looking back is very weird. Like in my AP US History class, we watched the Lonesome Dove miniseries, for like a week. That’s what we did to prepare for the AP US History test.

KW: That is just all you need to know.

CW: Needless to say, I didn’t do particularly well on the test.

KW: You have this trick in the book of having the traditional good guys not being very good. Brooke, and Sugar are pretty ruthless, but I was pulling for them. So I was curious how you went about building empathy, and were you conscious about trying to make them empathetic? Or did it just happen? Do you like Brooke and Sugar?

CW: Totally. I like everybody in the book. As characters, at least. They all do horrible things, for the most part… but that’s partly because every time there was a character I thought was too good, or too easy to side with, they would wind up fucking their life up with a bad decision or some bad information or some other weird accident. People are flawed and things go wrong. That just feels realistic to me. We’ve all made bad decisions and, sometimes, they’re irrevocable. Some things don’t get better, and you have to live with that. I mean, lots of things do get better, but some mistakes are permanent. And that’s not to say a mistake can’t turn around and become a blessing later. It works both ways. Anyway, I didn’t worry too much about trying to make the characters empathetic. For me, when I start imagining a character, I care about them maybe a little too much already. So it’s actually kind of a struggle for me to keep things interesting and honest and not just be like, “Oh, I love you so much. Look at you living your little life.”

III. ROAMING, AND ROAMING

KW: I was curious if you wanted to talk about Sugar. Do you find it alluring to write about people who are not themselves?

CW: One thing I’ve said about the book, or tried to say, is that it’s exploring the strangeness of the expectations people have of us and that we have for ourselves. I think it’s sort of impossible to live up to either, because what imagine can never really be exactly what is. I think that can be a source of great pain, but also it can also maybe be a source of great personal triumph, because if you can acknowledge it, and just accept that you’ll never be exactly what people think you should be, or what you think you should be, then you’re closer to actually loving yourself. Not that I have ever accepted it… So I guess I don’t know what I’m talking about. But Sugar isn’t concerned with his identity. Or with loving himself. Sugar is just living his life. He’s always lived his life the way he has, and so has Brooke. Even though they encounter a lot of people who…

KW: Don’t know how to classify them…

CW: Don’t know how to classify them, don’t know what to think about them, try to say all kind of things about them, and make all kinds of assumptions about them, and it never works. But also no character’s assumption about themselves work all that well either. Like we were talking about before, a lot of people think they’re very good in the book, and they do really terrible things. And a lot of people think that their way of living and thinking about life is going to get them through it safely, and it doesn’t.

KW: Yeah. There’s always also this question of what is home? The characters are searching for a home wherever they go.

CW: Yeah. There’s no “safe” place to settle in the book. Even the characters who have a lot of power are pretty aware that it isn’t going to last for very long. They’re like, “This is my little moment, but something’s going to happen eventually.”

KW: Yeah, it was interesting just to look at these people looking for their place. They really are ghosts on a landscape, destined to keep roaming, and roaming.

CW: And roaming, and roaming.

KW: The women in this book seemed tougher than the men. What does being tough in this book look like to you?

CW: Martha has allegiances that a lot of the other characters don’t. She protects people, and she strives for some kind of order and basic decency in the world. And Mary was raised by Martha, at least in part. So Mary’s idea got this idea that the world is not all bad. There are people who will protect you. There are things to look forward to. There’s music. Most of the other characters don’t have that.

KW: They have a resilience the men don’t really have.

CW: Brooke and Sugar are pretty resilient.

KW: Everyone has some resilience; they have to, in the book. But the women took the least shit of anybody. Changing gears for a minute, I think you have a really interesting publication history, and I was curious if you’re going after big publishers or if you just really love indie publishing and what’s going on in indie publishing and want to stick there.

CW: It’s hard to say, really, because I’ve never really been approached by a big publisher and then turned them down. When I finished my first book, I sent it out to agents and I got a few responses that were positive, but they wanted to make all these changes that ultimately didn’t feel all that thoughtful. Nothing I was presented with felt right for the book. So I figured, okay, well this isn’t the way, I guess. I’ll try this other thing. Then that worked.

But I really like independent presses. Every independent press I’ve worked with has seemed to genuinely love the book they published, and it felt like we were working on a project together, putting a book into the absolutely bonkers literary landscape of today. Also, the independent presses I’ve worked with have all had really distinct personalities. They’re unique presses doing unique things, managed by interesting and passionate people. My impression is that there is a lot less bullshit on this side of the fence, but it’s hard saying, not knowing. For now, I’m just focusing on getting the next book written. Then I’ll worry about what to do with it.

Excerpts of Haints Stay can be read at the Offing, Midnight Breakfast, and Numero Cinq.

This conversation originally took place at Skylight Books, you can hear the recording and other conversations as part of the Author Reading Series Podcast.

Colin Winnette is the author of several books, including the SPD bestseller Coyote (Les Figues 2015) and the book being discussed in this interview, Haints Stay (Two Dollar Radio 2015). He is an associate editor of PANK magazine. He lives in San Francisco.

Transcribed by Julia Schwartz