A Conversation with Joshua Cohen on PCKWCK

Most authors give interviews when they’ve been done with their books for more than a year. After the long processes of copyediting, cover-approval, and book-tour scheduling, the actual composition of the book is a distant memory. The following conversation with the novelist Joshua Cohen was conducted last Tuesday, when he was about 40 percent finished with his new book, PCKWCK (his tenth)—and, for a few hours every day this week, the newest novel in existence.

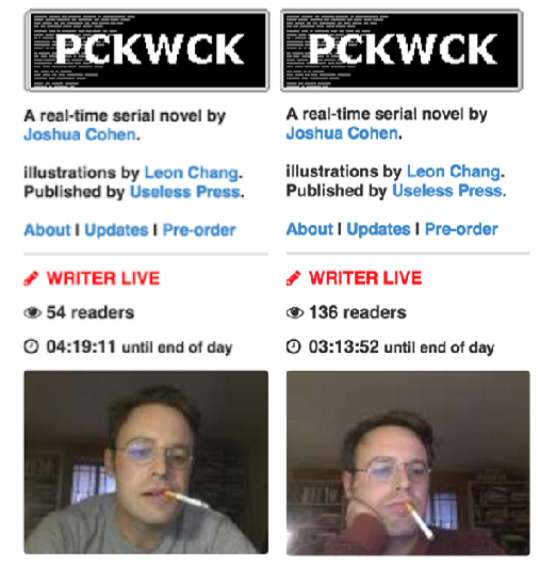

Cohen, whose last novel, The Book of Numbers, was widely celebrated as the most sophisticated and successful literary engagement with the internet to date, is writing PCKWCK live, in real time, over the internet. Every day this week, between 1 and 6 p.m. ET, visitors to PCKWCK.com see a blinking green cursor where Cohen, holed up in a basement in Brooklyn, is presently writing or editing the text. Users can post comments in a carnivalesque (e.g., anonymous and unmoderated) chatroom that occupies the book’s right-hand margin. And they can fill out a questionnaire that aggregates data that Cohen uses to formulate the next chapter of the book.

The project was conceived by Cohen and Useless Press, a collective that produces data-driven internet experiments. On Friday, the text of PCKWCK will be taken offline and the book, along with many of its comments and other user-generated data, will be published in a bound edition, with all proceeds going to the ACLU.

I spoke with Cohen over the phone minutes after he finished his second day’s shift. He was exhausted, and drank Negra Modelo.

—Andrew Leland

I. PCKWCK

THE BELIEVER: It’s pronounced Pickwick, is that right?

JOSHUA COHEN: I’m trying not to pronounce it.

BLVR: Okay.

JC: It’s loosely, thematically based on Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers, one of the most famous—if not the most famous and most successful—early serialized novels. That’s the story of the Pickwick Club, which is a group of British gentlemen who go tear-assing around the countryside in pursuit of knowledge, and they end up really getting drunk and getting into fights with high hilarity along the way. But in my rewrite, Pickwick seems to have become a military contractor that extraordinarily renders people and tortures them.

BLVR: Including your narrator?

JC: Including my narrator so far, yes.

BLVR: Well, that suggests my first question. Which is that seeing what unfolded the first two days, there has to have been some degree of preparation.

JC: There wasn’t actually that much preparation beyond reading The Pickwick Papers and walking around, thinking about it. For me, this is an...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in