An Interview with Graphic novelist Chester Brown

I first encountered Chester Brown’s starkly beautiful cartooning in a Canadian Literature class. His graphic novel, Louis Riel, had recently unearthed a piece of uncomfortable Canadian history—the execution of a 19th century political leader—and liberal arts professors across the country were collectively swooning over a comic book they could finally approve of. I too was impressed, if only for the book’s extensive “Notes” section—unusual for a genre where pictures usually replace most words. I argued with his notes in the margins. “Why exaggerate the linguistic divide?!” I scrawl-yelled nonsensically on one page.

Only a couple of years later, I found myself arguing with Chester in the margins of his next book, Paying For It, a graphic memoir about paying for sex, which this time included not only an extensive notes section, but a full-length manifesto for the decriminalization of sex work. By then I was an intern learning Photoshop at the publishing house Drawn & Quarterly, making sure the margins were properly aligned before the book went to print. “It’s not that I totally disagree with you,” I wrote in the back of an advanced copy, “I just think the argument is more complicated than you are making it out to be.” His writing can sometimes feel like he’s chosen to argue with you personally, after getting to know the contents of your brain.

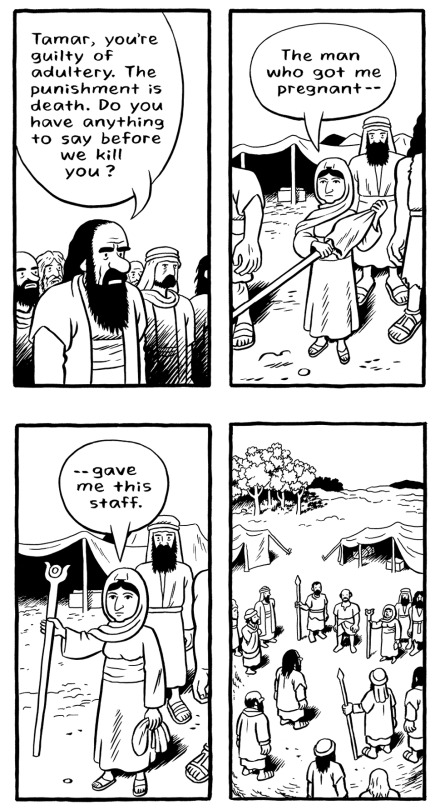

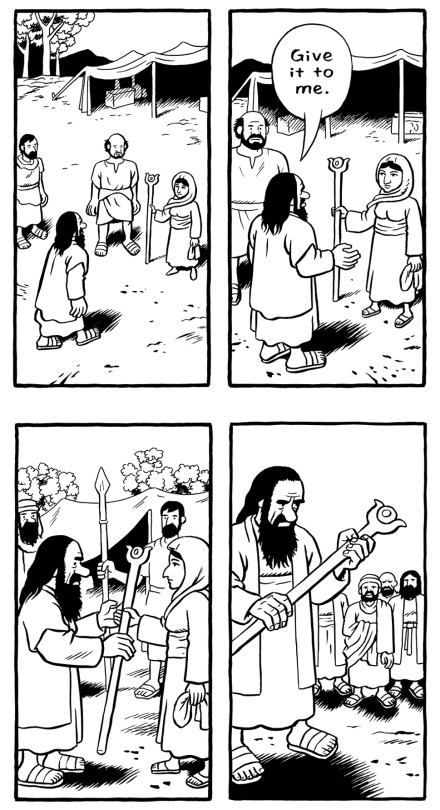

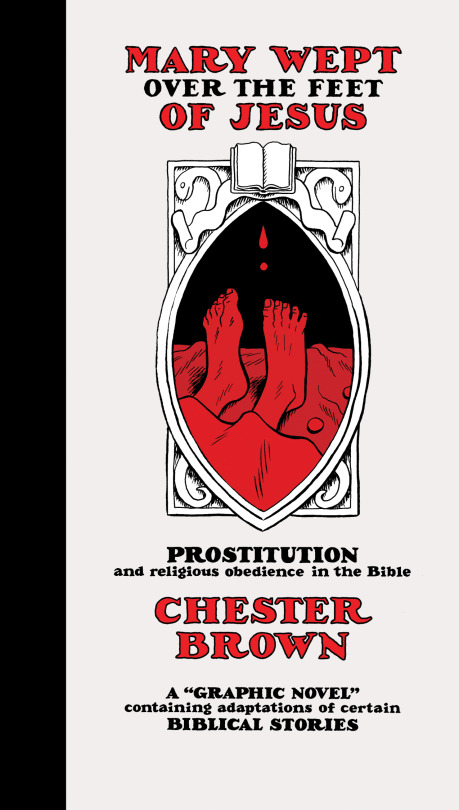

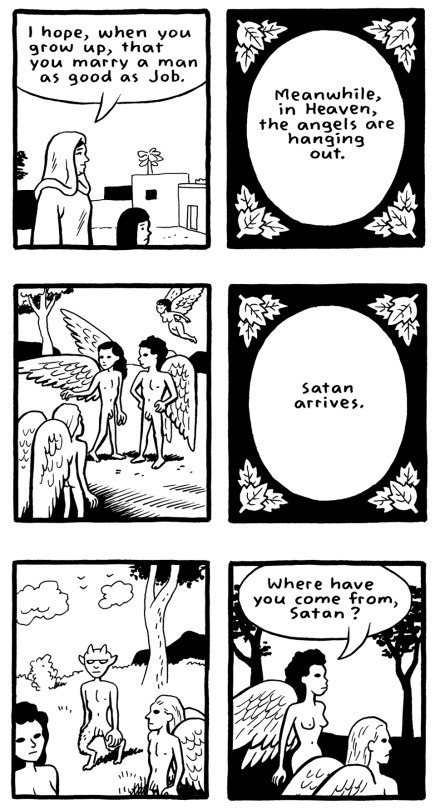

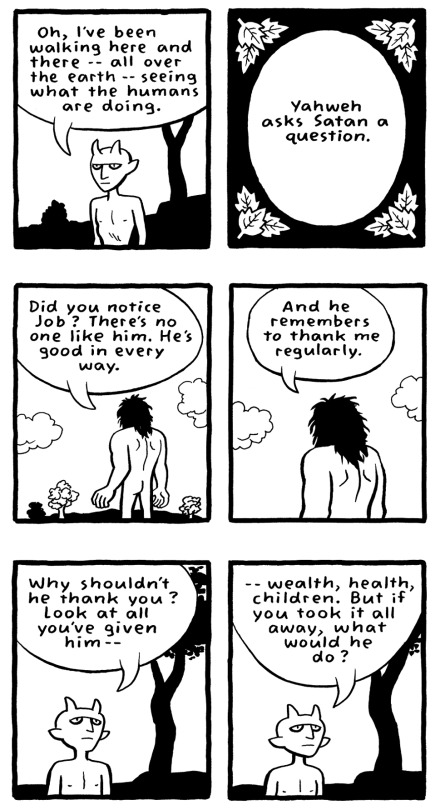

Now, after my third time reading Chester, I’ve come to expect and appreciate the margin-arguing experience. It’s not every day that a book can engage its reader fully enough to keep her up all night considering her position on prostitution. This is what Chester does best, and what he continues to do best in his latest graphic novel, Mary Wept Over the Feet of Jesus: prodding and unearthing the uncomfortable, forcing you to engage, raising your blood pressure a touch. Mary Wept contains several graphic adaptations / interpretations of Bible stories that deal with prostitution in some way, and his major controversial claim is that Mary, the mother of Jesus, might actually have been a prostitute (hence, the mystically-explained pregnancy). I didn’t have as many margin-arguments with this book, but I definitely had some.

The thing is, in person and over the phone, Chester is not even remotely close to the man-behind-the-margins who I had imagined myself arguing with. He is actually the kindest, most non-confrontational cartoonist I’ve ever had the pleasure of speaking with. It’s hard to believe he is the same man behind such strongly-articulated claims as: “we should all be paying for sex.” But this is part of his brilliance. When we spoke over the phone last month, I immediately forgot my margin arguments and instead just had a really pleasant, honest conversation about faith and biblical scholarship.

—Shannon Tien

THE BELIEVER: My background is “super lapsed Catholic”. I know my Bible stories a little bit.

CHESTER BROWN: Does that mean you went to church every Sunday? Or…

BLVR: Sometimes even during the week.

CB: Wow.

BLVR: I’m not practicing anymore, but the book brought back a lot of memories.

CB: I could never go all the way over to being completely an atheist. But I certainly went through my agnostic phase for a while.

BLVR: Could you tell me a little more about your own spiritual beliefs and background?

CB: Both of my parents were Baptist. We went to church every Sunday and I had to go to Sunday school and then when I was older, to the actual church services. At a certain point we changed churches. From about age seven or eight we started going to the local United Church of Canada, which, as opposed to the Baptists, is quite a liberal church. They ordain women now and have gay ministers.

In my teenage years I started to question everything. By my early twenties, I was living on my own. I was no longer going to church anymore, and wasn’t really sure what I believed about God or Christianity. And then I met a young woman and we fell in love. Early in the relationship she made it clear that she was a Christian. She asked me if I was also a Christian, and I said, “Oh yes. Of course I’m a Christian.” But despite growing up in the religion, I wasn’t really sure what that meant.

I found the whole topic of early Christianity and the creation of the Bible really interesting. I read a lot of books of that sort. And also, I was reading the Bible itself. But that was the thing that took me in the direction of being agnostic because biblical scholarship points out all the contradictions and all the reasons why the Bible can’t be the literal truth. I’ve gone in and out of calling myself an agnostic, or calling myself vaguely religious without having a name for what I am. These days I’m back to calling myself a Christian, even though I don’t believe that Jesus was divine.

BLVR: Why do you think you would never lean all the way toward atheism?

CB: I see too much meaning in life. To me, one can only be an atheist if one thinks there is no meaning. And everything seems meaningful around me.

BLVR: Mary Wept is essentially a layman’s interpretation of the Bible. But Catholics, for example, aren’t really allowed to interpret the Bible; the Pope does that. Protestantism makes it clear that everyone’s free to interpret the Bible as they please, but did you ever think, “Who am I to question the traditional interpretation of these texts?”

CB: Yeah, there is a much stronger tradition within Protestantism of interpretation of the Bible. And, of course, that has led to this ever-growing list of schisms within Protestantism. Really everyone is making up their own religion. The Protestant tradition just talks about it more openly than Catholics do.

BLVR: Another thing I’m wondering is: arguments for the empowerment and valuation of sex workers—and also just female sexuality in general—can be found in many areas of literature throughout history. Why the Bible specifically, for you?

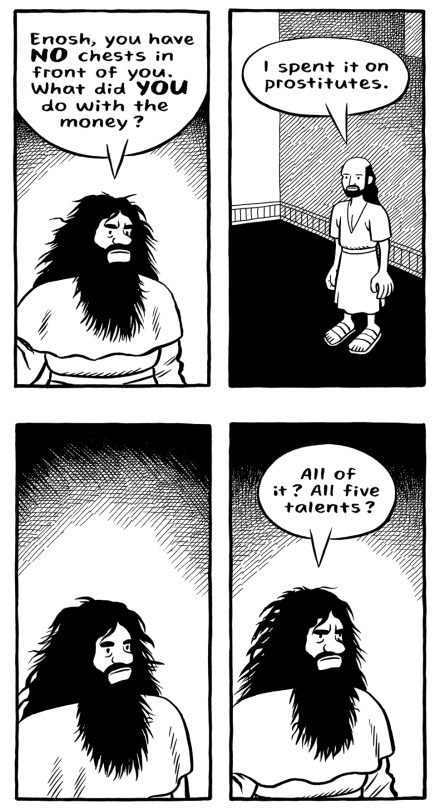

CB: My previous book advocated for sex worker rights, although it came from an autobiographical perspective. This time around the book was triggered when I encountered an alternate version of the Parable of the Talents. I found this alternate version of the parable that deals with prostitution. The biblical version of the story does not have prostitution at all.

I became convinced that the alternate version was the way that Jesus actually told the parable. Once I decided to do that story, I recognized the connection to the Parable of the Prodigal Son. I began to see connections to other biblical stories, and suddenly I realized I had a book on my hands. The whole process of creating the book was exciting for me: writing the script, doing the drawings. I enjoyed it more than I usually do, creating graphic novels.

BLVR: Why do you think that is?

CB: As I said, I grew up in this religious family, and my mother would read children’s versions of the Bible stories to me and my brother and. We loved them. I really have a deep affection for these stories.

BLVR: What were some of your favorite Bible stories from back then?

CB: From the Hebrew scriptures, probably my all time favorite is the one I got to put in this book: the story of David and Bathsheba. The moment when David is condemned by Nathan has always struck me as very powerful. I also really love the book of Ruth: the story of the deep love Ruth had for her mother-in-law. That might be the most powerful love story in the Bible.

BLVR: That’s interesting. Between a mother-in-law and her daughter-in-law. Not the traditional romantic love story.

CB: Right. It’s not a romantic love story, although some people project romantic love onto it. Some lesbians like to interpret it as a lesbian love story. I think that’s going a bit far, but I can see why they would do that.

BLVR: Do you think there’s such a thing as a “correct” interpretation?

CB: If we’re talking about the book of Ruth, I don’t think it has any historical basis—or I doubt it does. I believe there was an original author of the book and I believe that author did have an intent in creating the story. So, we read the book and we have to guess at the intent. Every reader’s doing that with every text. With modern writers it’s a little bit easier because usually there are interviews like the one you’re doing with me now where the author will make more explicit his or her intentions in creating a work. Unfortunately we don’t have interviews with the author of Ruth, so we read the text and we interpret [Laughing].

But yes, of course more than one interpretation is possible. This book of mine is a book of biblical interpretation. It’s going to be up to the readers to decide whether or not I’ve correctly interpreted things.

BLVR: Speaking of readers, who did you write this book for?

CB: It’s for anyone interested in either biblical matters or sex work matters, but I’ll admit—I’ve got a few friends who are in the sex worker rights movement, and I also know some sex workers who aren’t as politically engaged, it was them I was most thinking about when I was creating the book. I was thinking “Oh wait till they read this part!” But obviously I hope it appeals to people outside the sex worker rights movement too.

BLVR: That’s interesting. Because when I read it, it seemed most to me like an argument for people outside the sex worker rights movement, or who might take part in what you call “whorephobic” behaviour.

CB: There’s that too. But people who are strongly whorephobic, I don’t expect this book to win them over. I think they’ll have their own reasons for dismissing it. You never know. While I was on this book tour I met a person who I’ve been corresponding with by email and she first started writing to me after she read Paying For It and she had been very much anti-prostitution. And reading Paying For It completely turned her around and she’s become very pro sex worker.

BLVR: How does that feel to you when you’re able to see the effect that your work has on changing people’s minds so immediately?

CB: Not all of my books have been an argument, but I do enjoy books where the author makes an argument. That was the case with Paying For It and Mary Wept. If readers accept what I’m saying and think I’m correct, I love that. But I also understand that’s rarely the case. I don’t expect each reader to buy everything I’m saying. I try to make the book entertaining even if you don’t accept all of what I’m saying.

BLVR: Is it harder to deal with criticism when the subject is so close to your heart, like in Mary Wept and Paying For It?

CB: Yeah. There have been reviews of Paying For It where I was—I guess “upset” is the right word, though it sounds a bit strong—fired up reading the review. But I’ve got to admit that those reviews are also fun to read. I enjoy encountering the opposite point of view from mine. The world would be boring if everyone believed the same thing. I also think the world would be a better place if the laws against sex work and sex worker clients weren’t there.

BLVR: Right. One of the most controversial things you suggest [in Mary Wept] is that Mary the mother of Jesus was a prostitute. Does this idea make Jesus more or less attractive to you as a spiritual leader?

CB: It did make me see his teachings in a different way. It made me more likely to interpret the Parable of the Talents the way that I ended up interpreting it. I think Jesus had a friendly attitude towards sex workers. That does make me see him in a more positive way.

BLVR: Does the difference between seeing Mary as a victim and seeing her as an agent of her own fate affect your sense of Christianity?

CB: I don’t know if that idea changed how I was thinking about Christianity. Originally when I first wrote the script, I had nothing about Mary Magdalen, who was very definitely portrayed in the Gospel of John and also in the Gospel of Luke as a prostitute. And thinking about the scene where she anoints Jesus, it occurred to me what a strange thing it was, that a prostitute would be the person who anointed Jesus. The anointing of Jesus was significant because that was the ceremony that made Jesus a Christ. The words Christ and Messiah both mean “anointed one”. For the person who did that anointing to be a prostitute, it seemed obvious to me that that person must have also had some sort of spiritual authority, which turned my thinking in a completely different direction.

BLVR: An equally powerful interpretation for me is that Mary Magdalen was a “sinner” but that Jesus chose to hang out with her anyway.

CB: Yeah that’s the traditional interpretation, that Jesus saw her as a sinner and befriended her. That position is articulated in the Gospels. Personally I think that the Gospels are incorrect on that point. I think Jesus didn’t think the so-called “sinners” he hung out with were sinners. He didn’t necessarily believe they were doing anything wrong. But that’s my opinion.

BLVR: By the way, I love when the angels are just hanging out in heaven in Job.

CB: [Laughing] Yeah everyone seems to be pointing to those panels, where they’re just standing around.

BLVR: The story of Job just captures everyone’s imagination. We can all imagine asking “Why did this terrible thing happen to me? What did I do to deserve it?”

CB: It is the fundamental difficulty with the religious point of view. If there is a god, why does god allow bad things to happen? It’s a difficult one to answer.

BLVR: Do you think that story of Job satisfactorily answers the question?

CB: It does for me. And actually you asked me earlier what was my favorite story from the Bible and it didn’t used to be but during the creation of this book, Job definitely did become my favorite story from the Hebrew scriptures because I think it’s brilliant. I think the person who wrote it was a genius.

BLVR: You mention somewhere in your notes that during biblical times prostitutes were thought of as women who had made a “choice”. And for me that word is really hard. I’m just wondering if you think these stories would be different if they had been told by the women themselves, if the prostitutes’ voices were the main voices. Choice is at the heart of the sex worker rights movement, right?

CB: Yeah. Look, if we’re talking about the situation today, there are definitely women who have been forced into the work or strongly coerced, however you want to phrase it. There are women who would not have chosen to be sex workers. But it seems to me, and certainly it’s the belief of all the people I encounter in the sex worker rights movement, that the vast majority of sex workers do choose the work.

People who are against sex work are able to point to the women who have been forced, who genuinely are trafficked, and say “This characterizes all of sex work,” and I think that’s false. Although, if we’re talking biblical times, women had fewer options. Really your significant options were “marry a man and let him support you” or “become a prostitute”. And where you’re not reliant on one man, you’re reliant on many men who are going to give you money.

BLVR: Yeah it really complicates the term “choice” in that scenario. How much of a choice is it, really?

CB: I mean we’re all “forced” to work to get money. When I was younger I worked in a photo lab and I didn’t want to do that work, but I had to have money to be able to buy food and pay my rent and so on and so I worked in that photo lab and working in that photo lab was not an ideal situation, but I didn’t feel like I was being forced or had no choice. It was just the job that was available and I was willing to do it for that period of time until I was able to make a living as a cartoonist.

BLVR: I haven’t done the historical scholarship, but I’m a little bit uncomfortable thinking that most of these stories were probably told and retold or authored by men and thinking about how that affects their telling. I would just love to hear from Ruth herself, did she think she had a choice? The Bible is this patriarchal document that I think many women or sex workers might not think to look towards at all to justify their actions or existence.

CB: It is a question whether or not women had any role in the creation of the Bible. Harold Bloom contended that Genesis was written by a woman. And of course Genesis is the one that contains the story of Tamar. But who can say? I suspect even if the Bible was completely written by men, these are stories that were told and retold and I’m pretty sure that some of those storytellers were women at some point along the way, and that women to some degree shaped that material. But it’s impossible to say to what degree.

BLVR: So do you think the prostitutes have a voice in these stories?

CB: I do think that most of the Bible or all of it really was written by men and if that’s the case it’s hard to say that the voice of the prostitutes at that time is really coming through. Although the story of Tamar, it shows Tamar outsmarting the men around her. That does feel close to the voice of the prostitute.

BLVR: What religious rules and laws do you live by? And then on the other hand, what kind of commandments have you broken?

CB: [Laughing] Really the only important rules I think are the significant ones that Jesus pointed to, love god and love your neighbour. Do I break those laws? All the time. There are definitely times when I’m angry or annoyed with people around me and I’m not seeing them with the loving heart that I should. But I do think that the more you approach life and everyone around you with a loving heart, the better your life will be.