Ian Brennan on Field Recording in Rwanda

They were standing in the dark, their eyes downcast and furtive, and holding only one guitar between them. From one hundred feet away, I knew instantly that there was something special about them, a feeling one is lucky to experience even once in a lifetime. By that point, for over two weeks we’d already visited literally every recording studio in the capital [of Rwanda], Kigali, and surrounding areas, and listened to hundreds of artists, all to no avail.

We even attended a Kigali music festival where every performer seemed to be nothing more than a cookie-cutter version of a corresponding Western celebrity—same dress, affect, gestures, intonation, and hyperkinetic, but empty moves—with the only alteration being that the local language was grafted on top. (In the darkness that night, groups of pre-adolescents kept strutting up to us in mass, busting moves, “calling us out” to a dance-off, for which we were clearly out of our league and probably quite wisely declined.)

The meeting with the band, the Good Ones, had been set up through a mutual friend—someone who was quite talented himself, but was adamant that they were far better. The instant the band opened their mouths to sing, it was as if the universe reached down to tap me on the shoulder and say, “What these guys do is precious and rare. Don’t fuck it up.”

It felt like being carried away on a wave, but with no fear of drowning.

Earlier on the trip I experienced a cross-cultural, mini-epiphany when, Akim, who had driven us to all four corners of Rwanda in search of music, angrily ejected from his car stereo the 8-track tape that I had found of 1970s Rwandan singer Kagambage Alexandre. Akim immediately replaced it with the only collection he owned. It was of Mandarin pop, the strain that is played in cheesy Chinese-American restaurants.

Alexandre’s music featured vintage synths and elegantly analog saturation that would make a Brooklyn hipster weak in the knees. But, to our local friend, the recording just sounded like “God” music and the saccharine tripe from Asia was “much cooler,” which he made ultra-clear by way of his endlessly looping it at all hours throughout the multitudinous miles, making our way southwest by following the lines of satellite dishes like sextants.

Since the multitrack was “lost” in transit by the airline, the entire Good Ones’ album had to be recorded on a video camera. Fortunately, the old-school camcorder had two XLR-inputs, allowing for the connection of higher-grade microphones. I was provided little choice but to set up two ribbon condenser-microphones that I’d had for decades, and position each one in the gap between the three seated singers (two of whom also played guitar), in a quasi-stereo. I used a chair for one mic-stand, and a potted plant for the other—duct-taping the mics to each of them. I then rolled the dice: having set the band up, seated, on a covered porch with their backs to a wall that provided some natural reverb, as well as helping shield away much of the external sounds, from at least that one side.

The session was proffered under the disapproving eyes of many of the locals who declared the band members “filthy street bums” and ridiculed their “old-fashioned” music. One elder declared, “I’ve never even met such trashy people before.” Often, I would look up and catch glimpses of faces peering out, sardonically, at them. That after the success of the record overseas, many of these same individuals became the group’s most enthusiastic supporters, thereby modifying their personal memories as to their own initial opinion, proved once again the universality of human nature: that hypocrisy is not exclusive to Hollywood, everyone loves a winner, and things that are too alike or “too close to home,” tend to be the most threatening (thus, the love-hate dynamic of most families).

From where I am sitting, unadorned but thoughtful lyrics of theirs, like the following, stand toe-to-toe with some of the best romantic poetry from any canon.

I remember the day when we first met and I left right away,

and that is the day when, Belthilde, made herself known to me.

When I met her, I remained there for a little while, chatting.

I knew her deeply, I kept her in my heart.

Their simple, direct, and plaintive love songs are sung in the street dialect of the outskirts of the nation’s capital, and speak more to the healing power of peace than a thousand academic treatises or preachy goodwill ambassadors ever could—literally four of the songs on their debut record are titled with the names of the amores whom they are written for. And their follow-up album continued this trend.

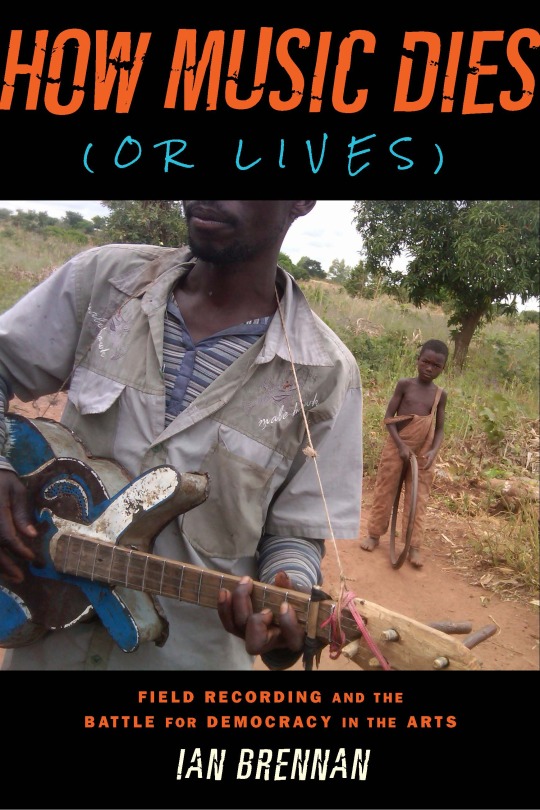

They are as punk rock as they come: barefoot, bandaged, and jaundiced, armed with broken, mismatched-stringed, and borrowed guitars, but singing angelically from amid a landlocked country that the world abandoned… literally.

Some sad lessons from Rwanda are how radio played such a sizable role to incite hatred and violence, with one tribe seizing the lone major broadcast signal in the country, and then using it around the clock to convince others to attack. Due to an ensuing onslaught of disinformation, the masses were mislead to believe the exact opposite of what was occurring—that the aggressors were actually the victims and that, therefore, the aggressors needed to kill the victimized tribe first, as self-defense. This is a portent reminder that the mass-media issues grappled with here in this book are far from merely philosophical in nature. And this knowledge makes it particularly chilling today to hear a European media giant’s catchphrase proudly proclaim, “One nation, one station.”

Like so much strife in this world, fear was at the core.

It is astounding to think that Rwanda’s most recent genocide was so severe—claiming the lives of at least one-eighth of the citizens, by even the most conservative estimates—that it can almost erase the fact that two other massacres (in 1959 and 1973) preceded this biggest one. Those unthinkable, earlier injuries have become all but forgotten internationally. For the survivors, though, the effects linger. Yet, throughout the populace, suffering similar to their own is so widespread and commonplace that few wallow in having had family members killed. Strikingly, the majority opt for the more subdued verb “died” instead or “murdered,” in such sharp contrast to the glorified culture of victimization that sometimes plagues America.

What we didn’t learn until later is that the band actually serves as a spontaneous realization of the unification of Rwanda’s three tribes, with the original trio’s members each having Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa (Pygmy) origins, respectively.

Later, while overseas I witnessed the attempted rapport, but insensitivity, of people attempting to speak French to the band. French was the tongue of the colonial rulers who had spurned the country and its people after the massacre broke out. So it hardly is a welcome sound. Not to mention that three out of four members were from the rural areas where formal schooling ends at an early age and they had never learned French, beyond basic greetings, even though in their formative years it was the nation’s official language.

And it is languages that usually continue to occupy long after the formal rule has ended. As an example of this, in Portugal, after almost two hundred years since their empire’s fall, there are 2,000 percent more people who speak Portugese living outside, than within, the borders of that modestly sized country.

In the words of one elder Rwandan, “Yes, I know French fluently. But, no, I do not speak French. And I never will again.”

Years later, the lead singer, Adrien, explained to me that, “I can’t sing low anymore. I sing differently now. My voice has aged.” Counter to the general assumption that vocal tone drops as we mature, he felt that his had become higher with time and experience, so that he could sing more spiritually and “closer to heaven.”

The above is an excerpt from Ian Brennan’s How Music Dies (Or Lives).

All photographs by Marilena Delli.