We’re pleased to present a series of excerpts from Jane Ursula Harris’ forthcoming book, After: The Role of the Copy in Modern and Contemporary Art. Harris’ survey assembles key examples of the copy from the onset of modernism to the present, and explores the copy’s relationship to the western canon.

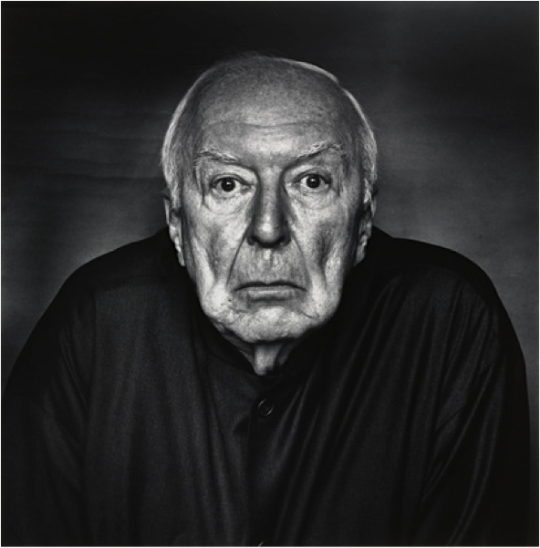

On Jasper Johns, John Cage, and Matthias Grünewald

Jasper Johns launched his career in the mid-1950s with paintings of targets, letters, numbers, and flags. The works embraced the representational and quotidian, reacted to the cabbalistic tendencies of late Abstract Expressionism, and are widely regarded as precursors to Pop and Minimal art.

Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954-55, encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood, three panels; Dimensions: 42 ¼ x 60

Over time Johns developed an increasingly complex iconography seemingly at odds with an emphasis on the concrete, revealing a paradoxical desire to explore the point at which visual logic—and meaning—fell apart. Through a scramble of illusionistic, abstract, and allegorical forms of representation, the line between the legible and the illegible was deliberately blurred. What remained consistent was Johns’ ongoing interest in the contingency of perception, and style—or surface—as subject.

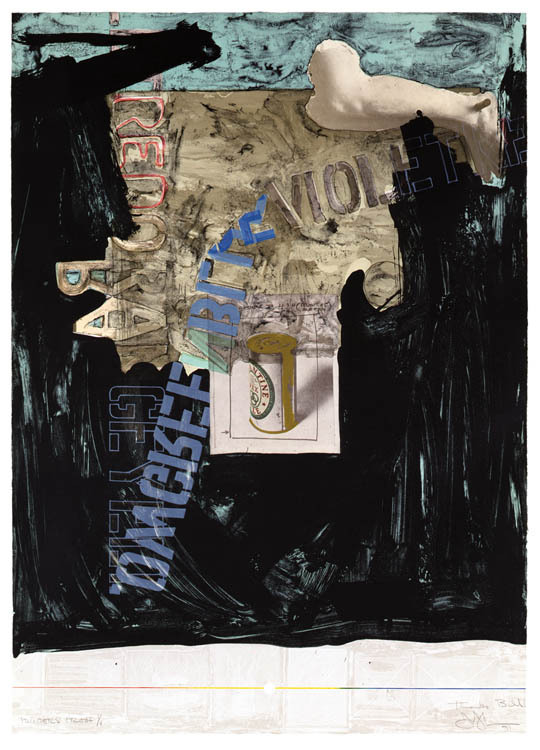

Jasper Johns, Decoy, 1971, lithograph with die cut, 41″ x 29″

Johns persistently refused to explain or categorize his work. He emphasized only process and the object itself. “There may or may not be an idea,” he once said. “And the meaning may just be that the painting exists.”

For some, the artist’s lifelong refusal to define his work extends its bid for indeterminacy; for others, the refusal was a call to crack the code: to find in his imagery and symbolism evidence of the personal.

Perilous Night, 1982, is a perfect example, having been read across a host of allusions to the historical and biographical. Based on Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, 1515, Perilous Night is a dramatic rendering of scenes from the lives of Christ and Saint Anthony. The mixed media diptych owes its title to a 1944 composition for prepared piano written by friend and colleague, John Cage (1912–1992).

Japer Johns, Perilous Night, 1982, encaustic and collage on canvas, 5’7″ x 8’ x 6″

Cage’s work was a pivotal piece in the composer’s aesthetic and personal life. He wrote it at the height of WWII as his marriage fell apart, and he began a relationship with the choreographer Merce Cunningham. A suite of six movements for prepared piano, Perilous Night is considered one of Cage’s most impassioned and autobiographical works. Its notable, however, that few listeners at the time were able to apprehend this emotion due to the work’s atonal nature. This troubled the composer, and led him to...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in