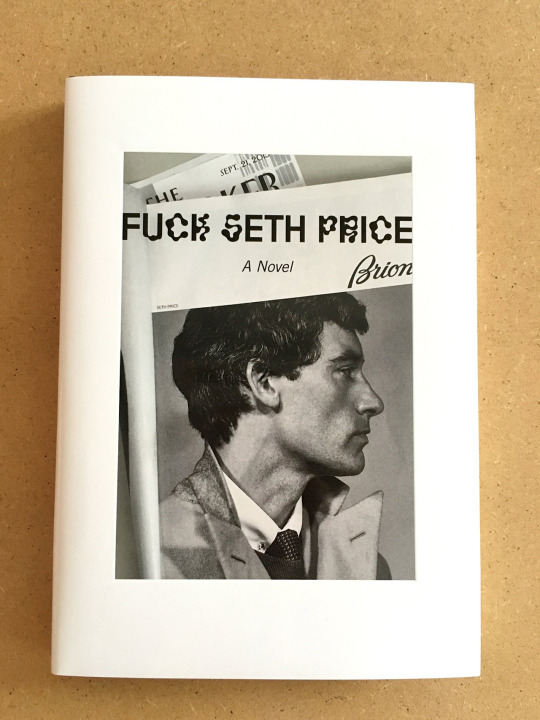

Fuck Seth Price, by Seth Price, 2015. Leopard Press, New York (pictured: second, hardcover edition).

Artist Books / Artist’s Novels is an ongoing inquiry by Stephanie La Cava that looks at the intersection between visual art and literature. Each entry is a conversation with an artist or writer whose books defy genre expectations and exist outside of the traditional form.

Volume 1: Seth Price

Volume 2: Paul Chan

Volume 3: Alissa Bennett

Volume 4: Ed Atkins

Volume 5: Ed Ruscha

Stephanie LaCava in Conversation with Seth Price

It’s astounding not more attention has been paid to the phenomenon of “artist’s novels,” a messy genre of fiction written by artists known for their visual and conceptual work. Henry Darger, Yayoi Kusama and Francis Picabia all wrote fiction. The latter, known primarily for his paintings wrote an autobiographical novel in 1924 entitled Caravanserail, which was reissued in 2013 in its original French. Picabia seems an appropriate grandfather for a new generation of artists interested in the creation and distribution of words.

Seth Price may be the heir extraordinaire with his genre hopping Fuck Seth Price (Leopard Press) about to be released in its second printing. The artist is known for his wit and playful approach to the distribution of intellectual and artistic properties. In a pivot of standard publishing practice, Price has chosen to release this hard cover as a follow up to the original paperback.

His first novel, How to Disappear in America was published in 2008. It was classified as such in the July 2015 issue of Harper’s Magazine in which Fuck Seth Price was excerpted. The book, however, is a compilation of writings found on the Internet. Price’s 2008 Essay with Knots is a visual tableau, nine plastic panels screen printed with his 2002 essay Dispersion, the written work was also available in stores and online. This interview was carried out over email correspondence earlier this year.

—Stephanie LaCava

STEPHANIE LACAVA: In a 2002 essay, you mention Mark Klienberg asking in 1975: “Could there be someone capable of writing a science-fiction thriller based on the intention of presenting an alternative interpretation of modernist art that is readable by a non-specialist audience? Would they care?” Did this foreshadow your “Left Behind” project?

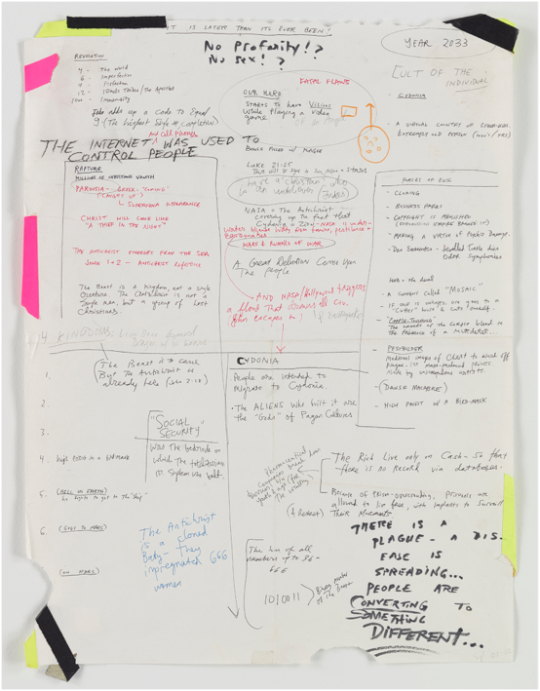

SETH PRICE: No, it came later. I saw the Klienberg quotation in 2002, and it went with a lot of stuff I was already thinking about. Right after 9/11 I read an article about the surge of interest in the Left Behind series, which is an extremely literal-minded extrapolation of the Book of Revelation. I got interested in writing an apocalyptic, evangelical, thriller with the aim of insinuating it into that reading public, as art. Before that, in 2000 and 2001, I’d been experimenting with writing in an automatic, procedural way. I tried to do a line-for-line mutation of Ernst Junger’s “On The Marble Cliffs,” where I would rewrite each sentence by arbitrarily inverting the meanings. If the sentence was “She walked up the hill,” I’d write, “He walked along the plain. “I have no idea what that was about. It went nowhere, though. I couldn’t pull off the evangelical thriller, either.

“Study for a Christian Novel,” Seth Price, 2001-2002. Pen, graphite, and tape on paper.

SLC: How did you arrive at the conclusion that you wouldn’t be able to pull off the project?

SP: I realized that carrying out the book the way I’d conceived of it would ultimately mean posing as an evangelical Christian. I was after a different kind of performance: to write a book and release it into the marketplace of books, where it would circulate but also perform its own circulation. The Dispersion piece moved in that direction, I think: it ended up functioning as an essay, but also as an example of what it, itself, was proposing. Positioning a piece of writing as artwork puts a doubling at the heart of the thing. You can take it as an authentic cultural product, something “honest,” but also as a gesture, as posing, which is dishonest. I like both/and, rather than either/or. Posing an artwork as another form of cultural production is drag. The Dispersion essay can be read as a “straight” art historical essay—I’m pretty sure it’s taught that way—or you can take it as an artwork that uses the art historical essay as a form, but also carries a performative dimension, in which case it becomes more nuanced. But also more suspect. There are curators and artists who have told me they never took it seriously, they thought it was trolling, basically. And I understand that.

SLC: What drove you to experiment with long form work like a novel, to pursue such a solitary endeavor?

SP: Writing a novel was partly an attempt to find another way of working. I was restless in the art world, but I can’t not make things, so I thought maybe I can make a little sidestep to another realm. But for this I needed to carve out space. For years I’d been trying to write literature and failing because my art production was taking all my time and energy. I was able to write weird little texts, and they fell right into place in the art world, but I couldn’t grapple with literature, which is a kingdom with its own customs. I couldn’t explore that world if I had to plan some looming exhibition, and manage a studio, all the while keeping up the mindset to experiment with new sculptural concepts or whatever. So I dismissed my assistants, and stopped producing artworks, and canceled or declined any upcoming exhibitions, and then I gave myself a year. Which was ridiculous, to think I could write a novel in a year. I kept writing more and more, and feeling ‘OK, now my chops are up,’ so I’d jettison the earlier stuff, but then that cycle just went on and on, and the thing I was writing crashed and burned. A couple hundred pages in the drawer. Fuck Seth Price only came later, it kind of popped off quickly after I’d declared the whole experiment a failure and started doing shows again, as if I needed to return to art in order to make it happen.

SLC: You performed part of Fuck Seth Price at the Whitney earlier this year. Here, you eschew the protracted engagement of the novel for an hour in performance…

SP: Performance enters into all of my work, on some level, and I think it has to do with impurity. My work is impure and self-contradicting, and that’s what performance is about. For years I’d been doing public readings of my own essays and books, and for a while in the early 2000s I was doing performances where I’d tell stories I’d written, and sometimes improvise according to audience suggestions. I’ve also got a body of video work with fairy tales and ghost stories that I write and read. So the Whitney made sense. The double glass partition in their auditorium offered a good way to present a novel, as an author trapped in a box, physically separate but on display, unable to hear the audience, or even see them, thanks to the lighting setup, and audible to them only via a wireless PA. So all the elements of the evening were pulled apart and made artificial, but at the same time it was live. I was all Lavaliered and spot lit, I slicked my hair back and wore makeup, and I had on this dumb outfit of black gym gear and ultra-white New Balance. It felt like a Silicon Valley product launch. It was fucking intense for me. The Whitney had scheduled a conversation with Charline von Heyl directly after the reading, but when I emerged from the glass box to sit and talk to her, I was still vibrating with another world, the heightened world of performance. I was incapable of returning to a place of answering a question, or even understanding one. Charline was not happy about that.

Seth Price reading from Fuck Seth Price at The Whitney Museum of American Art, November 20, 2015. Photograph by Filip Wolok.

SLC: Conversely, were you interested in making sure the reader has to live with the work for at least a little while when you published Fuck Seth Price? Were you considering the self-reflectivity of the character? Did you care about creating this protagonist—Seth Price—that appeals or endears himself to the reader?

SP: The novel is an example of autofiction, which is a trend now. I’d been reading contemporary literature intensively for some years, partly because I wanted to see what the current technologies were. The author/character was a technology people were using, for me it goes back to Eileen Myles calling Chelsea Girls a novel, or Chris Kraus’ books in the 90s, and more recently Knausgaard, and Sheila Heti, and Tao Lin, and Ben Lerner. I decided to use this because it was a current technology. It was my Left Behind move: “Ah, here’s a successful bandwagon…” I liked that the novel could be completely of its moment. It also allowed me to take advantage of the art world, my world, rather than try to enter evangelical discourse, or Young Adult fiction, the genre I tried to inhabit during my year writing. With art as a topic and a place I was writing from I was able to explore something I had license to exploit, but then to do it in a questionable way, to make it as indefensible as if I’d finished the YA novel. I could explore lines of thinking that took the narrator to absurd places, places I don’t necessarily agree with, that don’t represent what Seth Price believes. Again, it was about finding a place of self-contradiction.

SLC: Ingo Niermann and Alexander Wallasch did a novel on a veteran of the war in Afghanistan and played with idea of pretending the author was the actual soldier, knowing it would be a major success. Does playing the system like this become ethically okay if it’s an art endeavor?

SP: Well, that was part of my interest in the Left Behind series, back in 2001. It’s co-written by a suspect evangelical minister and a hack who writes as-told-to biographies, and it immediately was a perfectly weaponized best seller, so it looked like bad faith. But it was a successful piece of writing and it made a lot of people happy in a straightforward way and was affirmative. It’s also nakedly political, which is interesting: it transcends simply being a fantasy series because it openly affirms this controversial worldview that wants to make over the culture. It’s not subtle or artful, like in Tolkien or C.S. Lewis. At the same time, most of its readers probably wouldn’t see it as a political artwork. You could say the creators pick up and employ existing religious scripture and interpretation and exegesis as tools in order to generate the story, and also to address a vast and lucrative consumer audience. I’m saying that the series checks a lot of boxes for me. My thinking was, this veers close to the territory of art, where things can have double identities, triple identities, unstable interpretations. Obviously the authors wouldn’t see their project that way, and yes, fine, it has nothing to do with art. But you could say I used it like a springboard: “If I squint and blur my eyes, the cross wavers and comes to look like a big, negating X.”

SLC: You have written poems. Some argue that poetry is closer to visual art. When you take out your own handwriting and the free form of poetry, how do you see the artistry in the words of the novel? Would you say that fiction itself is a sort of visual abstraction?

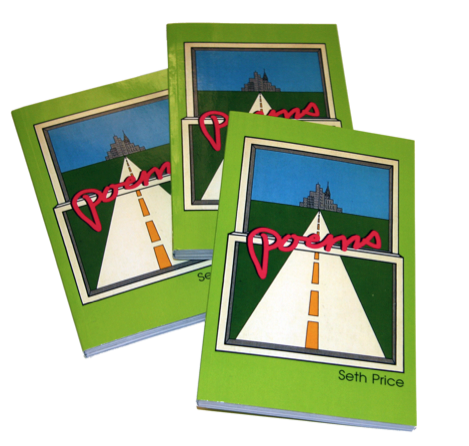

Poems, by Seth Price. 2003, Onestar Press.

SP: The Poems book was another art gesture, though: taking hastily written, random, notebook pages and calling them poems. They might now stand as poems, but I don’t think I’ve written poems. But I do think of poetry as the best model for most of my writing. Readers don’t put the same burden of subjectivity on poems that they do on an essay, because an essay is taken to represent an authentic and direct speech act. People take it to embody what the author believes, whether it’s an op-ed by Maureen Dowd, an essay by Stephen King, or a Martha Rosler piece. Whereas a poem is more slippery, you don’t hold it to the same standard. In poetry you know that the “I” and the “you” might be fictions and that the lines are performing. Pieces of mine like “Teen Image” or “Was ist Los” or “Lecture on The Extra Part,” or even “Dispersion,” are not written as enunciations of my position, except in a second-order kind of way. They’re experiments in voice and position and belief. That’s why some people think I’m fucking around, and get annoyed, and for them the meaning evaporates. But it’s closer to visual art, where you look at a piece from another angle, or in a different mood, and it’s just some piece of shit occupying space in a room, or it switches identities from clever maneuver to brute fact. Art is a place where you can experiment with a position to see if you believe it, to see if it’s tenable, or even interesting. Poetry, too. When you transpose this to the essay form you run into issues.

SLC: There is a funny notion of process in the literary world. You did studies or novels that you felt didn’t work before you wrote Fuck Seth Price. Does your approach to visual art/objects have a mirrored trajectory?

SP: No, probably not. The world of literature exists next to art and they share qualities of expression and topicality and formal interest, and a dialogic relationship to a history, and distribution and public, but really it’s all different. What’s experimental in art doesn’t cut it in literature, and vice versa. For me, writing was much harder than making visual art, and it was all consuming, which was scary, because at the end of the year I got nervous I might not be able to “come back.” The process of reception is also different. In literature the novel is held up as the ultimate form and authors are portrayed as whiling away the time between novels with reviews and stories and essays. But when the novels are out, you can just read them. With visual art, on the other hand, the fullest expression is the exhibition, and the exhibition is a temporary and quickly dispersed form, and few people will see all your shows, and shows aren’t usually well documented. So to an observer, bodies of artwork and thinking and sense eventually start to cohere, but this is fragmentary and obscured, and it takes years. It’s hard to really know what a good artist is up to, whereas you can get a sense of an author fairly quickly by doing some concentrated reading. This is why survey exhibitions are seen as important.

SLC: You said you’re in your second printing and now at work on the admin work of producing a museum show. I think of the line in your essay: “The art system usually corrals errant works, but how could it recoup thousands of freely circulating paperbacks?”

SP: If there is an art system, it has no problem doing whatever the fuck it wants, including corralling books and ideas. I’m done with anything that could be taken as a manifesto.

SLC: By the way, this is great: “with the twist of a kaleidoscope things resolve themselves.”

SP: As if!

This is the first of a three part exploration of sly and genre-bending approaches to the tricky landscape between literature and the visual arts, check back in the upcoming weeks for more.