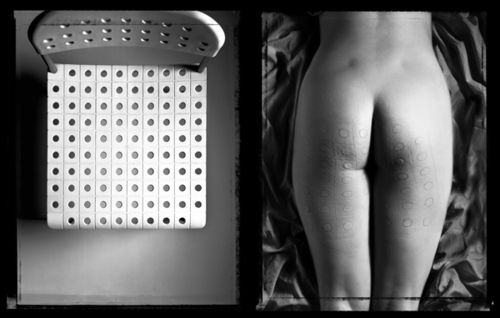

(Gabriele Basilico, Contact, 1984)

I was surprised when my friend Rachel Kushner told me that, having just finished her final edit for her first novel, Telex for Cuba, she was excited to start work on a second novel which would be set in the New York art world of the early 1970’s. I remember being shocked that she had already figured it all out and knew where she was going next… usually, when I finish a lot of work, I just want to stay in bed and sleep for a year. And so when I heard from her sometime later that she would be travelling to Italy to do research for the novel, I just assumed she had changed her mind and decided instead to write about Italian revolutionaries.

When I started reading The Flamethowers I was humbled and embarrassed to realize that I had underestimated her commitments. Set in both New York and Italy, parts of the book reminded me of social experiences in the art world so acutely I cringed with painful recognition as I read.

Ten years after Rachel interviewed me for the then very new Believer, I had the pleasure of driving with her across town to Santa Monica City College where we wandered the campus looking for KCRW. Far from my Eagle Rock studio where the first conversation took place with a cassette recorder, pen and paper, we found ourselves lost looking for the underground recording studios. We asked several students where it might be, and eventually, in a black room with headsets on, we had a conversation about The Flamethrowers.

—Laura Owens

I. A LACK OF AGENCY

THE BELIEVER: What I thought was interesting about the book is the lack of agency all these women have in trying to negotiate their world, and like the fact that this woman––who is this incredible motorcycle racer––goes to a dinner party and barely says a word the entire night––you hear her thoughts, but you don’t hear her voice.

RACHEL KUSHNER: Sure—maybe it’ll be the case that some people will be disappointed by her so-called lack of agency, and my rebuttal would be that maybe those peoples’ expectations have to do with literary conventions of heroism more than with real life situations that young women face. Or that they expect of my narrator a strength they think they possess, but the thing is, she doesn’t have it. She has her own strength, which isn’t about being the loudest at the dinner table. I was trying to render something that felt real to me for a very young person in New York City, meeting artists for the first time. The tone of the scene, also, is meant to fit the 1970’s, and I think my impression of that time––despite there having been all these amazing women artists, like Yvonne Rainer, Martha Rosler, Lynda Benglis, Mary Heilmann—is that the Minimalists were still totally ascendant. It was a very male world. And not just male, but macho, in a sort of clichéd way. Even in the 1990s when I was young and living in New York, I felt like I didn’t really have a right to speak until I had some purchase on the discourse and could sound smart.

BLVR: Right.

RK: And if I didn’t know a reference that somebody brought up––to interrupt their story, to ask them to explain the reference, was a way to let them know that they shouldn’t pursue anything with you beyond acquaintanceship. So maybe I was channeling a little bit of that. I hate to say it, but some men do talk a lot. I have been to art world dinner parties where there are a few people who are self-authorized storytellers, and they hold court, and they assume what they are talking about is interesting to everyone else, and there is a kind of tacit social pact that it is interesting, and that they will be allowed to speak until they’re finished. The late, great Walter Hopps was kind of like that, but he had the most terrific stories. And everyone would just listen. His protégé Anne Doran wrote to me and said she felt like Walter would have loved my book, which was, like, the best compliment. Maybe the portrayal of this quiet young woman and a bunch of silverbacks holding court would have seemed realistic to Walter.

But there were some other formal reasons why I had this scene that you’re talking about––the dinner party––narrated in the first person by a young woman, but also crowded out by other voices. Bolaño does this thing in The Savage Detectives where the narration is all being told by one person but it skitters among different voices of people who are telling stories in the book, just in dialogue, and I was inspired by that. I wasn’t consciously emulating him, but I think I was given a green light by that novel. So I let the male artists at the dinner table just go on and on, and I thought, wouldn’t it be funny if one of them holds court not by talking but by forcing everybody else to listen to a reel-to-reel tape recording of his voice?

BLVR: That was one of my favorite moments in the book. It took this idea of the monologue to another level that became incredibly comical and tragic and pathetic at the same time.

RK: Oh thanks. That was the idea, I guess. But I relate to him in a way, too. Once you start, I mean attempting to actually say something, where do you stop?

BLVR: I’m remembering seeing you read at the Hammer, and you read an essay based on a motorcycle race that I believe you partook in?

RK: That’s right––you came to that reading? It was like twelve years ago.

BLVR: Yeah. And it was really interesting that this character, who goes unnamed throughout the book––the main character––has this history with racing. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

RK: I had written an essay about an illegal road race on Highway 1 in Mexico, where you span the entire peninsula of Baja in one day. You have to average over 100 miles per hour to do that. And I was doing pretty well in that race, but I crashed halfway down when somebody pulled onto the road right in front of me, and there was a truck coming from the other direction, so I had no choice but to ride off into the soft sand on the side of the highway, which was incredibly lucky, because it was either cliffs or rocks on either side, all the way down, except in this one place. I was going 140 mph. There were people on the side of the road who had broken down, which was why this person had pulled back on the highway. So there’s proof, witnesses to the speed I was going … I was very lucky. I was basically fine.

BLVR: The character in the book also crashes––racing her boyfriend’s family’s fancy motorbike.

RK: She’s riding an Italian motorcycle––it’s a fictional make called Moto Valera. She’s on the Bonneville Salt Flats, where they do land speed trials. I’ve never done that. But when I was a kid I used to drive through the area, and I was always fascinated by it. We would sometimes stop there––my dad is interested in motorcycles and cars––and then I took a trip there by myself when I was writing the book, to watch the land speed trials and take in the environment of that scene. I was interested in having a character who was doing a land art project, like artists were doing in the early 70’s. Except for Nancy Holt and a couple of others, it was mostly men who were doing these projects. I had seen a photograph of huge arcing motorcycle tracks Michael Heizer had made at El Mirage Dry Lake in California. I thought, what if it’s my character who made these? Laura’s phone is buzzing. [laughs]. Who’s calling you?

BLVR: The Democrats. The Democrats literally call me four times a day.

RK: I forgot all about the Democrats.

BLVR: They still need money.

RK: At least it wasn’t the Republicans.

II. POCKET CUNTS

BLVR: I’m going to read one of my favorite little passages in the book that I thought was such a beautiful image that sort of illustrates this problematic thing that happens with women in the art world. It’s this character Lonzi who’s––can you describe Lonzi?

RK: Yeah, he’s a fictionalized futurist of sorts. He’s a little bit Marinetti, but he’s not Marinetti. He’s the leader of this avant-garde little gang in Rome around 1910, and they ride motorcycles and romanticize machinery, speed, war, violence, the future. But I just want to say one thing that doesn’t pertain to who he is in the novel: I named him after the radical and great Italian feminist Carla Lonzi, who wrote We Spit on Hegel. He has contempt for women but he invokes a really cool one every time someone says his name.

BLVR: Awesome. Okay, here’s the quote, “Women will be pocket cunts,” Lonzi said. “Ideal for battle, for a light infantryman. Transportable. Backpackable. And silent. You take a break from machine gunning, slip them over your member, love them totally, and they don’t say a word.”

RK: I wrote that?

BLVR: It’s amazing. I don’t know why the image of pocket cunt––just the sound of the words together, I think is totally amazing. Then there’s another moment where you talk about this man who actually has a hole in his pocket that he’s fingering, and he can’t find change to buy his girlfriend a hamburger in Mexico, and it’s sort of this illustration of how she thinks he’s so pathetic that he can’t even buy her a hamburger. I thought that was really interesting.

RK: Wow, yeah, I’m trying to link them through the value of the pocket. The second character you bring up is in the 1960’s––Burdmoore Model, who is a member of this anarchist street gang. There’s a warrant out for his arrest, so he flees to Mexico with his girlfriend, Nadine. They live in great deprivation—everybody gets rashes and fevers and bitten by fire ants. Then they make it to the border and are going to a McDonald’s and she’s like, ready for a hot meal. His wallet has wiggled through a hole in his pocket. He’s unable to buy her a hamburger. From her perspective, it is a massive and profound failing on the part of a man. If they’re going to play gender roles, then she needs to be provided for. But he couldn’t even provide her this most fundamental thing, a McDonald’s hamburger. I guess I was thinking of the misogyny in the anarchist gang in the novel: the women make fliers, mop the floor, or strip down. The men load weapons and talk up a big game.

BLVR: There’s a lot of twinning or doubling going on between the two stories: the Italian narrative and the New York narrative. There’s an insurgency happening in New York with the anarchist street gang, the Motherfuckers… How is it spelled, because it’s not––

RK: It’s spelled Motherfuckers.

BLVR: One of the main leaders, his name is Fah-Q?

RK: Yeah. His full name is Fah-Q Motherfucker.

BLVR: Fah-Q––that’s beautiful. So there’s an insurgency happening both with the Motherfuckers in New York and this group in Rome which is based on the student movements. Were you conscious of this doubling?

RK: I guess I was. It would be naïve to say I wasn’t. But the Motherfuckers were earlier—the late-1960s, and when I immersed myself in each world to write about it, I was only thinking about that discrete group, time, context, and not about manipulating any elements in order to produce parallels or emphasize differences. There were other doublings that I was aware of more pointedly. The blackout in New York in 1977, which was considered the “bad” blackout because people looted their own neighborhood shops and so forth, as compared with the “good” blackout of 1965 when everybody behaved and was genteel and they left businesses intact. The blackout of ’77 coincides in time with political actions in Italy that almost tore the country apart, and I thought of them as something like fraternal twins, although it wasn’t at all clear to me what they shared.

I was thinking about this march in Rome on a real day around which I constructed a chapter––March 12, 1977––an apotheosis of an era when people in Rome were taking it upon themselves to determine what they were going to pay for rent, electricity, public transportation, movies. I was thinking about that, and about the blackout, and I didn’t want to over-connect the two phenomena, but I felt that if I wrote about both maybe some secret coherence would reveal itself to me––or that it wouldn’t, but simply by putting them in one novel I would suggest to the reader that there was some kind of resonance between them.

III. BOXES WITHIN BOXES

BLVR: You’ve written about art for a really long time, and been a part of the contemporary art world through knowing artists, and writing in Artforum, and writing in catalogue essays, and various––

RK: Yeah, I guess that’s true.

BLVR: Do you feel like it gave you some permission to write about this scene because you have first hand experience?

RK: Probably yes? A lot of my friends—as you know, being one of them—are artists. I feel like I know it as a social world and a discourse, so yes, I probably self-permitted. I felt like I should do it, in fact, which is a bit egotistical. But so often when novelists try to do a scene that deals with the art world, if they get the smallest thing wrong, the whole thing––the whole ship sinks. You have to know the codes. But also I think people outside it have these misconceptions about the art world, and even a kind of hostility, so they try to do a sendup or a takedown and that’s even worse. To do that, you better know the milieu inside and out.

I’m familiar enough that it’s unlikely I’m going to screw up basic details. And my experience with artists probably inspired a lot of the dialogue in my book, if not directly, in a synthesized way. Which is how I like to write, not with specific real life people in mind, but drawing from out of the unconscious these characters who are made from some deep metabolic understanding of certain kinds of personalities. Everything in the novel has to manifest organically as I write it.

But I walled off a lot of art history and art theory and didn’t use any of that really at all. I felt my characters, some of them, knew it, and that was probably necessary that they know it, but I was certain that describing art and ideas about it would injure or even kill my novel. I kept all that off-screen. The reader knows they are artists but I wasn’t going to give long descriptions of what they make or what they think about what they make. I just think that doesn’t work in novels. It comes off as precious; everybody knows the fictional works are fake, and being “made” by the author. I have almost no descriptions of artworks. I tried to keep the actual presence of art in the background.

BLVR: I’m a painter, and sometimes I think about paintings within paintings, and something I really noticed in this book was how many stories within the novel there are. There’s this amazing story of a meteorite crashing into a woman’s home, and probably several others that I’m not remembering right now. You seamlessly weave together these beautiful little stories.

RK: Oh thanks. Well, I love it when you have done that, put paintings inside paintings. I mean, even as a child if there was a children’s book with paintings on the wall inside the image––like in Goodnight Moon—I always felt entranced, like I was seeing something more, a surplus of viewing that was not being controlled for presentation: as if the pictures inside the picture were “real” views, less authorized, because incidental. I guess that’s part of the playfulness when you, Laura, paint paintings inside of paintings—it suggests access to a more insightful view if you can see inside the picture something that wasn’t drawn by the hand of the picture maker. Of course it was drawn by the artist, but there’s the implication that it wasn’t. That the artist is revealing this other thing she did not draw.

BLVR: Yeah.

RK: Of course with your paintings, each one of those paintings is rendered in a slightly different style, and they have different frames, right? So each one of them is this little view into another landscape or space, and it’s sort of a joke. It’s very playful. Perhaps in a similar way, but inside the script of language, the constant talking of human beings, these smaller vignettes began to take form as I wrote. Eventually I realized that they pertained in some way to the structure, that they were like “holes” or “views” from inside the narration, which is first-person, and that the vignettes could incorporate all kinds of life that the narrator herself is not part of, has no access to. Part of my own education as a young person in the art world was listening to people be the raconteur. I wanted the reader to share the narrator’s experience of being the listener. Formally it was a nice challenge to me to see how much I could get away with before the reader goes––wait a minute, who is the narrator of this novel again? In one instance, late in the book, there are I think thirty pages basically that are all dialogue––one character is talking. And as you pointed out, there’s the photograph from Time magazine of the woman hit by the meteorite, and the narrator has a long rumination about her.

BLVR: The housewife.

RK: Yeah, and it’s funny because there really was a woman––sometime in the early-1950’s––who was hit by a meteorite, and I’ve seen a picture of it, but it wasn’t at all like I described it. I thought I’d seen a photograph of this woman when I was a child, and I assumed it must have taken place in the 70’s. I remembered it being the cover of a magazine, and the woman was sitting at her kitchen table, pulling down her stretch pants to show the bruise on her hip. As I wrote, I tried to recreate what it looked like in my mind, the look on her face, and then I got to this idea that it could make a person incredibly proud to have been hit by a meteorite. I mean, what are the chances? For me, an image—it doesn’t have to be a visual image, sometimes it’s a phrase, or an idea––that’s a way to start something. The image is surfacing for some reason. I’d been thinking about that photo since I was a child. Now you can find out everything because of the Google, and after I wrote the scene I looked it up––

BLVR: The Google?

RK: Yeah, and so the photograph in actual fact was black-and-white, not color, despite my having remembered it in color. And I had pictured the woman being kind of plump and comely, with a headscarf, sitting at a western-style kitchen table. I mean, maybe I was confusing it with the cover art of a Wanda Jackson record or something … because I was waaay off, which is fine. The photo was actually very grainy, and it was of a person looking half-alive and totally traumatized, lying in a hospital bed. So it really had nothing to do with my own riff about it. Except for the bruise. I had the bruise right.

BLVR: My brain’s going off on this sort of universal scene of domestic violence––it’s like she’s in her home, and she’s hit…

RK: Hmm, yes, I see what you mean. Being hit—perhaps one is ‘chosen’ for that, in a similarly complicated way. I didn’t think about the meteorite in terms of domestic violence, but rather, in terms of those two words: It’s domestic, and it’s violent. The impersonal violence of nature isn’t something we’ve really accepted.

Laura Owens is an artist who lives in Los Angeles and recently completed “12 paintings” at 356 south mission road.