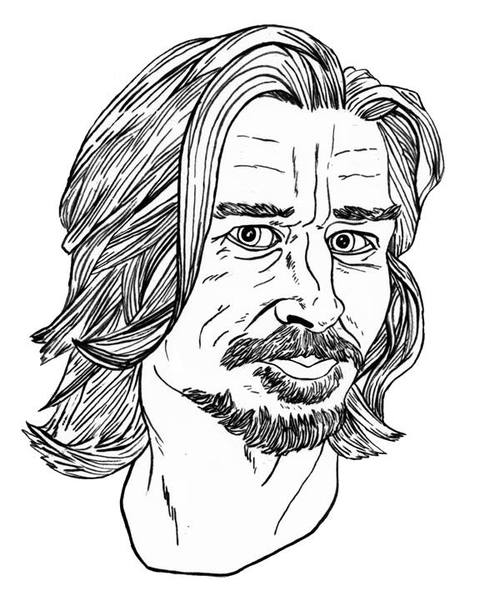

Karl Ove Knausgård enters the empty cinema in the Ingmar Bergman Center with a package of cigarettes in his hand and asks me where I got my coffee. He runs away to get a cup for himself before sitting down beside me in front of the white screen.

We’re at the festival “Bergman Week” at the Swedish island Fårö. Knausgård, his wife (the Swedish author Linda Boström Knausgård) and their three children arrived yesterday. I haven’t met Linda or the children; however, after reading Knausgård’s autobiographical series, entitled “My Struggle,” it feels like I know them. In the six books (of which two have been translated to English) Knausgård seeks to tell about his life and the world he lives in just as he has experienced it, and does so with a compassion, intimacy and sense of detail that absorbs the reader in descriptions of even the most trivial parts of everyday life.

—Rebecka Bülow

I. “A SENSE OF LIFE”

THE BELIEVER: Let’s start with a quote from “My Struggle”: “What I’m talking about is everyday life; the metaphor for that is death.”

KARL OVE KNAUSGÅRD: Oh shit.

BLVR: Yes, it’s quite heavy. I’m bringing it up because “My Struggle” is basically thousands of pages of everyday life. Did you write it because you needed to write about death? Your explanation is that death and the minutiae of everyday life are the things that are always present in life.

KOK: Something that I’m trying to achieve with these books is to create a feeling of here-and-now. And I do that, at least to some level – I tell about this, where we live our lives, this is what we have and it’ll be over soon, right? At the same time there is this feeling that we don’t really care and that we’re living our lives like they might last forever.

BLVR: You also often write about death without using metaphors. Many times your reflection is that in the culture where we live, you and I, we try to deny death.

KOK: I don’t mean to judge us—but the way we deny death says something about how we live our lives, doesn’t it? At least in Sweden or Scandinavia, you don’t have to search further back in time than maybe three generations to find another way to relate to death. People then had a different, closer relationship with death; at least it was like that in the countryside. There is a Norwegian author called Olav Duun who has written a fantastic novel about a rural society in the 1600s. On the other hand, I wouldn’t want to live like in that...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in