Ronald Kuhler was born in Teaneck, New Jersey, in 1931, the second child of an abusive Belgian mother and an often absent German father. His father, Otto, was an artist and industrial designer who worked for the railways, drafting streamlined, Art Deco designs for the next generation of locomotives. The family moved to Rockland County, New York, in 1938, and soon sent Ronald, a chronic bed wetter, to a series of boarding schools where he was ostracized and ridiculed by classmates, and often beaten by teachers. In the late 40s, the family relocated to an isolated and arid ranch in Colorado, where life didn’t become any easier for Kuhler. At home he was trapped with his family, and at school he was mocked by his peers.

Kuhler left the ranch in 1953 and moved to Denver. A year later, unable to find work, he enrolled in college. He had always been a skilled calligrapher, and in 1957, his friend, filmmaker Stan Brakhage, asked him to draw the titles for the four-part experimental film Dog Star Man. In 1962, Kuhler received a degree in history from the University of Colorado. A year later, he legally changed his name to Renaldo Gillet Kuhler. In the late sixties, after working for a few years as curator of history at a museum in Spokane, he moved to Raleigh, North Carolina where he took a job as a scientific illustrator at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. He retired in 1999, but continued to freelance as a scientific illustrator until his death in 2013.

Kuhler’s biography, however, isn’t even a third of the story.

Writer and filmmaker Brett Ingram, director of the 2009 documentary Rocaterrania and author of the new book The Secret World of Renaldo Kuhler (Blast Books), describes his first encounter with Kuhler on a city bus in Raleigh in 1994 this way:

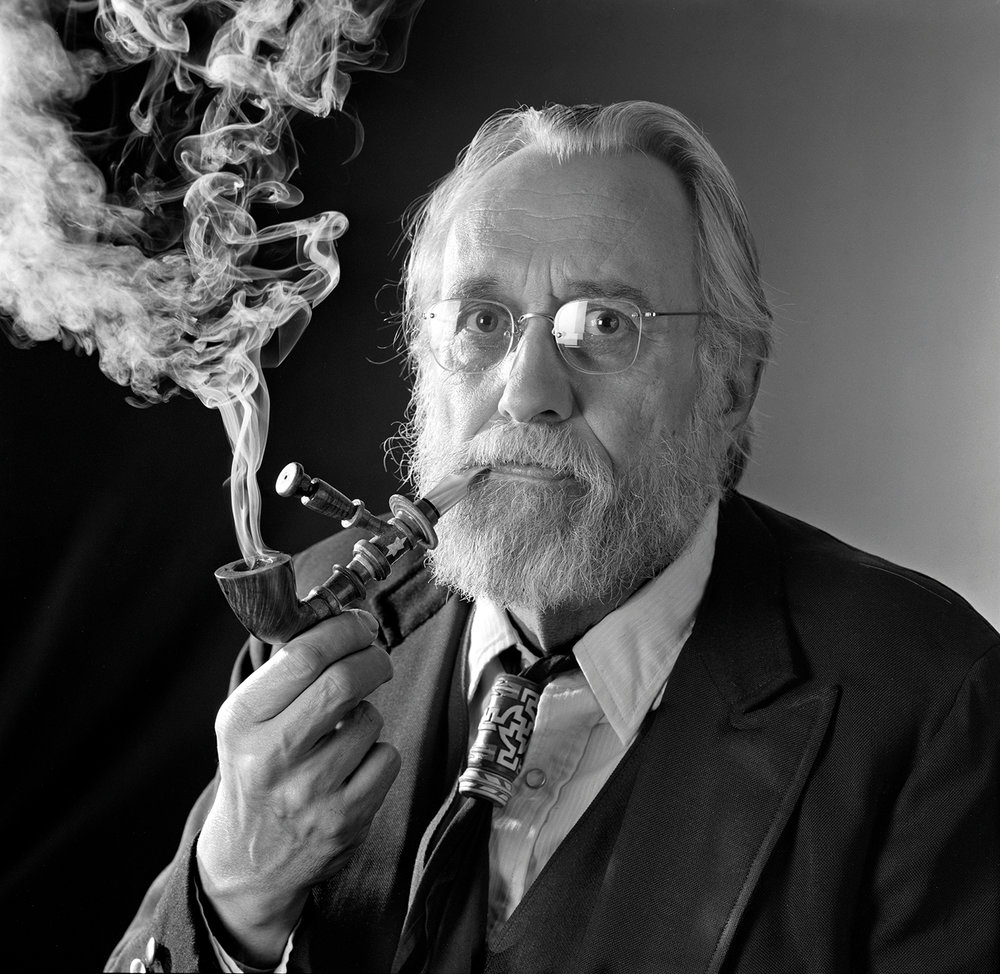

Six-foot-four and stout, with a bushy white beard and ponytail, he wore a custom-tailored uniform of indeterminate origin: a sleeveless Kelly green suit jacket with wide, black, notched lapels, epaulets, and brass buttons, a matching suit vest, yellow flannel dress shirt, a fleur-de-lis Boy Scout neckerchief, and tight-fitting knee-length shorts (“cotton-blend lederhosen”). His epaulets and neckerchief slide appeared to be hand-carved and bore matching insignia, a singular design integrating arrows, stars of David, and geometric Navajo patterns. White knee socks with Scottish garter flashes, black wingtips, gold wire-rim spectacles, and a plain black baseball cap completed his ensemble.

The stranger, Ingram writes in the book’s introduction, took a seat at the front of the bus and enthusiastically began extolling the virtues of public transportation to no one in particular. Although intrigued by the odd...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in