LITERATURE SICKNESS: EXPOSING REALITY’S MANY VALENCES

for Lynne Tillman

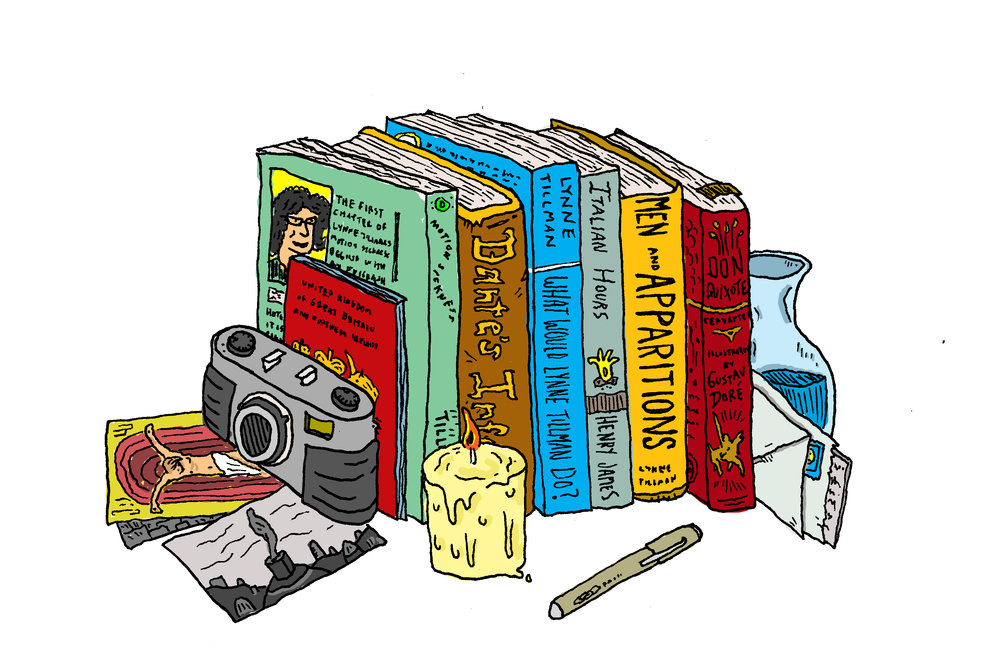

The first chapter of Lynne Tillman’s Motion Sickness begins with an epigraph by Flaubert: “I am… the fellow citizen of all that inhabits the great furnished hotel of the universe.” It is no coincidence that the chapter’s opening line echoes Flaubert’s epigraph: “Paris: I am in my hotel room, on the bed, reading The Portrait of a Lady, and nursing an illness I might not have.” This subtle grammatical gesture—the faint echo of Flaubert’s line—lends Tillman’s narrator an extra-literary dimension. The “I” that guides us through Paris, Florence, Istanbul, London, and Amsterdam among other places and that reads voraciously in various hotel rooms across European and non-European cities is, I propose, suffering from a case of literature sickness—a feverish obsession with reading and with viewing the world through the lens of literature. Despite being one of Tillman’s most overlooked books, Motion Sickness, locates itself firmly in the tradition of such idiosyncratic and paradigm-shifting novels as Robert Walser’s The Walk, W.G. Sebald’s Vertigo and Rings of Saturn, Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, Mat Johnson’s PYM, Gail Scott’s My Paris, Teju Cole’s Open City, and Enrique Vila-Matas’ Dublinesque and Montano’s Malady—all books whose DNA, in one form or another, can be traced back to Don Quixote (1605), the quintessential book about books.

Part philosophical diary, part travelogue, and part an examination of the constraints national narratives place on personhood and our perception of others, Motion Sickness begs to be read alongside a broad constellation of books that simultaneously use literature to expose the unreality of identity and to examine the poetic and geo-political dynamics of space. It is a book that deserves to be located within a lineage of novels that are securely tapped into the echo chamber of literature; books that are purposively in conversation with other books and within whose pages the genetic code of their literary forbearers is embedded. Though I am using Don Quixote as a point of reference here, it’s important to note that to write about reading is a preoccupation that runs through the history of literature: think of Petrarch reading Saint Augustine, Virgil reading Homer, Dante reading Virgil, Woolf reading Mansfield, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz reading Plato, Cervantes reading the chivalric tales, Acker and Borges reading Cervantes, Coates reading Baldwin. The list goes on. What I’m getting at is that in recasting an older text and/or embedding within their own text a rapport with another, each of these authors has created a...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in