There are two ways to make a powerful laser. The first is to cram as much light energy as possible into a relatively long pulse duration. This requires a huge amount of light energy, necessitating large, complex structures and a vast array of generators. This was most notably exemplified in the case of the Death Star. Commander Moff Jerjerrod (the Imperial officer supervising the construction of the second Death Star) was interested in the dialogue between size and power, and an enormous laser proved to be a potent metaphor. Each of the twelve sectors of the main reactor symbolized a central value of the Empire, and the resulting laser represented the unified will of the member-states. The endless power grid produced sufficient energy to generate a long-lasting pulse, symbolizing the enduring glory of Emperor Palpatine.

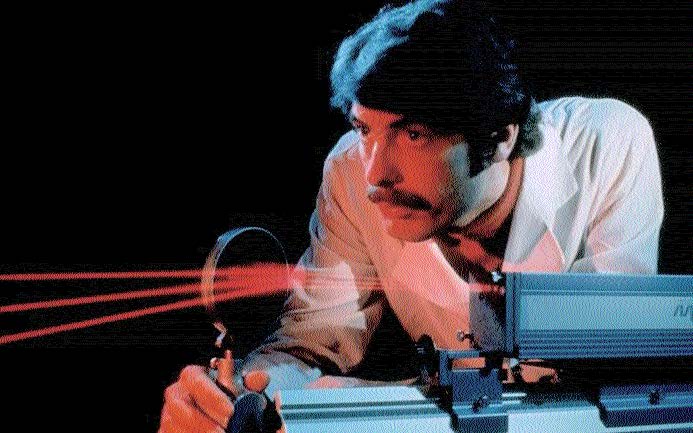

For better or worse, this level of resources isn’t available to most researchers. The second approach is to compress a modest amount of light energy into as short a pulse as possible, shorter than a trillionth of a blink of an eye, thereby creating an Ultrahigh-Intensity Field using Chirped Pulse Amplification. This method, pioneered by University of Michigan professor Gerard Mourou, proves much more feasible for scientists and family members on a shoestring. The necessary components cost about half a million dollars, all told, and the system can be set up on an ordinary table. An ordinary table! This laser should not be mounted on a table made from varnished driftwood. Also, the table should not be covered in a Southwestern-themed tablecloth. There should be no inexplicable sticky spots. Leave science to the scientists.

How ultrahigh is this intense field? Exactly how amplified is this chirped pulse? High. Pretty fucking chirped. This laser can create an electric field a million times the breakdown field of most materials, pressure a trillion times stronger than atmospheric pressure, and temperatures as hot as the center of the sun (a thousand times hotter than its surface). The physical conditions that can be recreated are those that existed one millisecond after the Big Bang. This whole affair lasts only one femtosecond. A femtosecond is a quadrillionth of a second; in other words, one million-billionth of a second. There are as many femtoseconds in eight minutes as there are whole seconds in the history of the universe.

The tabletop laser can focus all this power on a spot just a few micrometers across—perhaps the size of a newborn baby. Why would scientists want to subject an infant to this kind of wattage? That is the question being debated in Internet chat-rooms and on glossy magazine covers across the nation. The current consensus seems to be this: in order to create a...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in