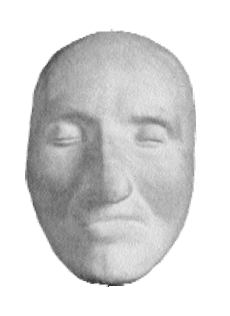

Thomas Paine keeps staring at me from this old book, his nose bent to one side like an aged boxer’s. He’s had a tough life and an even tougher afterlife. I’ve spent the last few years pursuing his bones: they were stolen in 1819, and since then have reappeared everywhere from a New York sewage ditch to a Paris hotel room, with occasional stopovers inside statues and pieces of furniture. As I pursued the skull and bones of Paine, perhaps it was only a matter of time before I crossed paths with this book by Laurence Hutton, the man who once possessed Paine’s face… not to mention Franklin’s, Lincoln’s, and Aaron Burr’s faces too.

When Hutton is remembered today, it’s as Mark Twain’s editor at Harper & Brothers. But it was his obsessive pursuit of plaster death masks that once caught the public’s attention; Hutton could confidently lay claim to having “the most nearly complete and the largest collection of its kind in the world.” Like many Victorian memento mori, his resulting 1894 opus Portraits in Plaster is an object of unnervingly beautiful craftsmanship: its thick and creamy paper bears scores of photographs of the immortal yet all too-mortal. Here are Keats and Coleridge; there are Swift and Johnson. Twain’s editor had gazed into the face of Whitman and had cradled the molded cheeks of Grant and Sherman, the latter pair vanquished at last by a truly implacable foe.

The actor David Garrick, looking for all the world like a fifth Baldwin brother, proved to be an unusual life mask acquisition. Though life and death masks alike enjoyed a vogue in the nineteenth century, bolstered in no small part by the popularity of phrenology, Hutton’s distinct preference for death masks was actually rather humane of him. “The procedure of taking a mould of the living face is not pleasant to the subject,” he noted. “In order to prevent the adhesion of the plaster, a strong lather of soap and water, or more frequently a small quantity of oil, is applied to the hair and to the beard…. quills are inserted into the nostrils in order that the victim may breathe during the operation, or else openings are left in the plaster for that purpose.” The subject—be he a pope, poet laureate, or president—was then unceremoniously made to lay his head back in a big pan of wet plaster, whereupon the artist proceeded to smear the glop over him. Then he had an agonizingly motionless wait as the stuff hardened. Death masks are different, though; the only discomfort involved is that of the onlookers. A death mask is the visage of a man whose guard...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in