1. The Barthelme- Saunders Paradox

Named for American writers Donald Barthelme (1931–1989) and George Saunders (1958–), neither of whom is considered a realist. The Barthelme-Saunders Paradox (occasionally called the Mimetic Paradox or, vulgarly, the BS Paradox) is typically represented by contiguous postulates:

BARTHELME’S INEVITABILITY

POSTULATE (1987)

I think everybody is a realist. I do not think that we have a choice. The nature of consciousness is such that we are always doing realism. Consciousness is always consciousness of something. We are always writing about the world. I have a formulation for this idea: art is the true account of the activity of the mind.

SAUNDERS’S IMPOSSIBILITY

POSTULATE (2004)

Realism is nonsense, when you think of it. I mean, there is no such thing. Nobody writes realism, if realism is defined as “fiction that is objective and real and not distorted, but is just, you know, normal.” … What I find exciting is the idea that no work of fiction will ever, ever come close to “documenting” life. So then, the purpose of it must be otherwise.

The paradox can be resolved easily enough by showing that the two writers rely on radically different definitions of realism to arrive at their postulates. Barthelme defines realism as the accurate correspondence between the artist’s mind and art—accordingly, everyone is a realist. Saunders defines realism as the accurate correspondence between art and reality—accordingly, nobody is a realist. Barthelme’s definition emphasizes intent; Saunders’s definition emphasizes technique.1 (But both writers agree that the distinction between realism and nonrealism is specious.) When you apply different definitions to the world, you get different categories. Fine, but the problem now is that the term realism has been stretched to meaninglessness (a process called Terminal Elasticity). When a term can be rendered useless by two different lines of argument—and those lines are mutually exclusive—that term has ceased to do much work. Realism, as Barthelme said in the same interview from which his Inevitability Postulate was derived, “is kind of a sloppy category.”

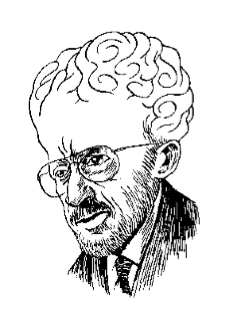

2. Doctorow’s Brain

The infamous “Doctorow’s Brain Problem” goes like this:

Imagine two contemporary American philosopher-novelists, celebrated and cerebral, beards gone gray. They are similar in intellect and accomplishment, but they differ markedly, even diametrically, in their views on the relationship between literature and reality.

The first of these imaginary men, call him Novelist A, is an old-fashioned optimist about the possibility of human knowledge. For evidence of the human mind’s ability to grasp the world beyond it, he’ll point you to Galileo, Jonas Salk, or the Curies, Marie and Pierre, the wedded codiscoverers of radium. He might go tell you to kick a...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in