Quid in tanta lacuna dictum, non expunto. So wrote the German classicist Johan Ludwig Heiberg in 1906, after peering at a particularly inscrutable section of the medieval manuscript he had just uncovered in a Constantinople library. “What in such a large hole could have been said, I will not guess.” Heiberg was attempting to translate the words of Archimedes, arguably the most important thinker in the history of science. His frustration arose from the fact that, sometime in the thirteenth century, the Archimedes text had been scraped off, cut up, rebound, and written over to make a Greek Orthodox prayer book, rendering the ancient mathematics nearly impossible to read.

It might seem incongruous for a German professor to be translating ancient Greek into Latin in Turkey in the twentieth century. But this is the least remarkable of the book’s oddities. The text Heiberg faced had been written in the ninth or tenth century CE—a copy of innumerable previous copies stretching back to the original treatise Archimedes wrote in the third century BCE. And almost immediately after Heiberg’s discovery, the book disappeared for ninety years. The Archimedes Palimpsest, as it is now known, is indeed like a pit into which we can peer forever and never see the end.

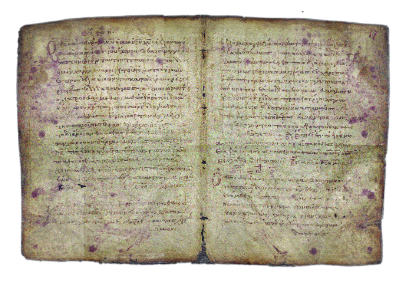

We begin, as always, with a copy. The long pages of animal hide bear twin columns of dense script—an antique hand already obsolete—interrupted occasionally by geometric figures. Triangles and squares bisect one another; rectangles nestle in circles, as stray line segments float alongside. The document is instantly baffling, its authority suspect. The scribe, raising his knife, pauses to consider the text before his eyes. But it remains unreadable. Ghosts of their original selves, the words and shapes retreat from his gaze, lost within layers of impenetrable meaning. The work of the blade is quick enough, though never complete.

Now scraped nearly clean, the manuscript leaves are cut in two and refolded in preparation for the new text. In a priest’s practiced hand, he writes his prayers perpendicular to the faded lines below. Soon only traces of the older script and the elegant diagrams can be seen under the newest text. And, in the words of the freshly obscured treatise, “Though many worthy eyes will see it, they all will not know it, and none will perceive it.”1 On the first page of his new book, the scribe writes: “This was written by the hand of presbyter Ionnes Myronas on the 14th day of the month of April, a Saturday, of the year 1229.”2

This was the creation of the Archimedes Palimpsest—a book formed by the erasure of other books. The word palimpsest comes from the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in