The Atomic Priesthood

If the nuclear waste repository under construction inside Nevada’s Yucca Mountain endures for a thousand years—if a seismic event does not cleave the mountain’s shell of volcanic rock, if the buried radioactive materials do not seep into the water table—it is likely to outlast our own civilization. If it endures for ten thousand years, it is likely our languages will no longer be intelligible to the humans that have replaced us. Government officials are not known for taking extraordinary measures to guarantee the well-being of people outside their constituencies, much less their millennium, but public anxiety about the project is such that the usual charge of guarding the safety of our children and grandchildren has been extended: we must now include distant descendants whose only inkling of our existence might be a mountain pregnant with decaying plutonium and uranium isotopes. The Department of Energy’s Office of Civilian Radioactive Waste Management must also find a way of sending a message to whatever comes after us: stay away from Yucca Mountain.

In 1957, the National Academy of Sciences recommended that the spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste stockpiling at 121 temporary storage sites in thirty-nine states across the country be buried deep beneath the ground. In the late ’80s, the government chose Yucca Mountain—a mahogany ridgeline in the Mojave Desert an hour and a half from Las Vegas—as the site for a repository. Construction and the laborious process of site characterization began in earnest, with a projected opening date of 1998. Once underground storage chambers had been readied, marble-size pellets of waste would be packed into metal canisters and transported to the site by rail and truck. Upon arriving, they would enter the five-mile-long tunnel connecting the north and south portals. Workers in radiation suits would then shepherd the waste into geologic drifts a thousand feet beneath the surface, where they would stay for up to a million years—the half-life of the most hazardous materials.

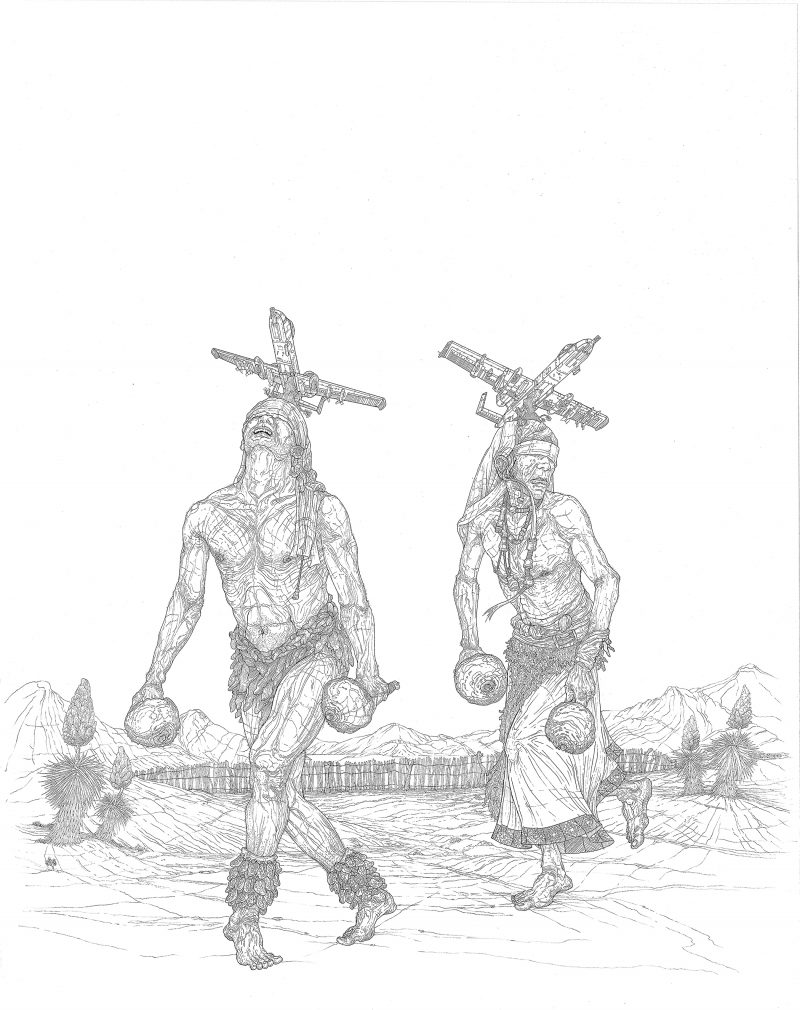

While the DOE’s main concern is ensuring the inviolability of the waste casks, what it calls the “monumental task of warning future generations” has been given serious consideration—site plans currently call for twenty-five-foot-high perimeter markers in the six UN languages and a new universal symbol for “nuclear waste repository.” But this will only be sufficient for a couple thousand years: in a 1984 study commissioned by the Office of Nuclear Waste Isolation, the late linguist Thomas Sebeok concludes there is no precedent for any language remaining comprehensible over three hundred generations. (The world’s oldest clay tablets date only to 3000 B.C.E.) Human thinking does not maintain its continuity with the past for very long, and the interpretation of an old language relies on...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in