For more than five years, Roger Ballen has been photographing the eerie and sometimes-mystic relationship between birds and people. The results are a growing affection for birds and his latest (twelfth) book, Asylum, which captures his ongoing obsession with haunting, surreal, black-and-white worlds.

—Caia Hagel

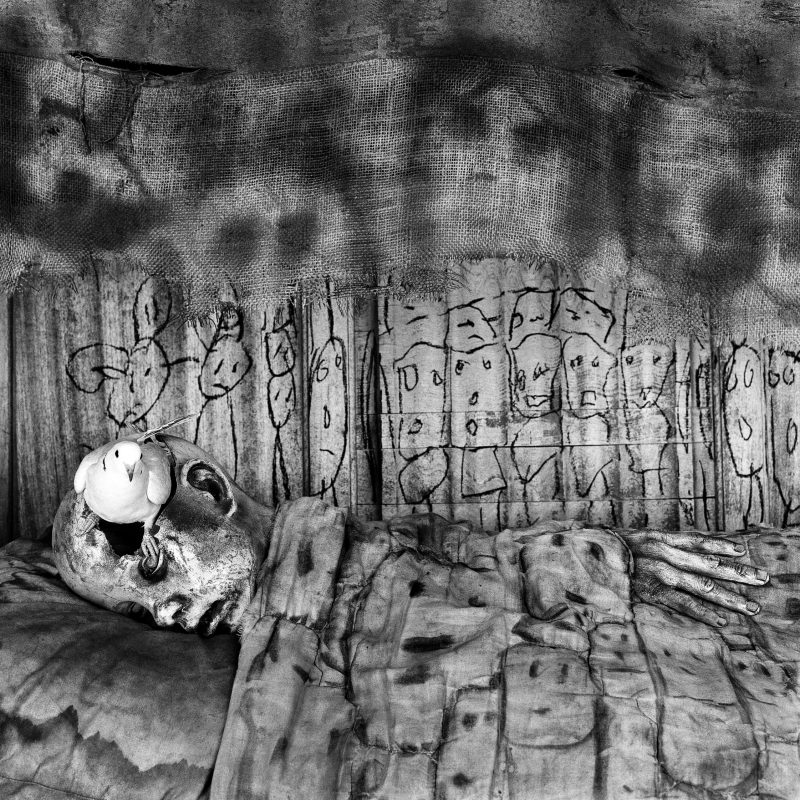

Deathbed

Deathbed, 2010. Archival Pigment Print. 90 × 90 cm.

Photo by Roger Ballen. Courtesy of the artist

THE BELIEVER: Tell me about Deathbed.

ROGER BALLEN: Since 2008, I have been photographing in a house in Johannesburg. It is physically similar to most of the places I have been working in for the last thirty years: claustrophobic, sparse, and dark. It’s a place of refuge for people who come from other parts of Africa or who are from broken homes, have no money, no job, or are escaping domestic violence. There are a lot of animals in this place.

This photograph began with my noticing the back of a bed that had drawings on it, and a blanket on the floor. I put the blanket next to the bed. There was a broken skull lying around, so I put it there, too. It’s very hard to make a good still life. One has to create deeper meanings. Birds were flying around the room so I grabbed one and stuck it on the skull but there still wasn’t the right balance. There were people milling around, kids and some other residents of the building, helping me, catching birds and so on. I had an epiphany that the image needed a hand, so a boy crawled under the bed and put his hand through a hole in the blanket. All of a sudden the scene made some sense. Birds rarely stay still, so it took a long time to create a strong relationship between the skull, the bird, and the hand. In two or three rolls of film, there was probably only one good picture.

There are thousands of little pieces that each image consists of. I start with nothing and work with live things and dead things, working very, very hard. I don’t have any idea what attracts me to this place, these people, and these animals. I work with my instincts.

In my photography, I explore only one thing: my own interior. I am obsessed with exploring the other side of my psyche that I want to open up. Through photographing, I find parts of my interior that I had not discovered before. It’s like dropping a fishing line into a dark ocean—what are you going to bring to the surface? Something that looks like a squid? Something that looks like a fish? Some kind of vegetation? It’s very mysterious.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in