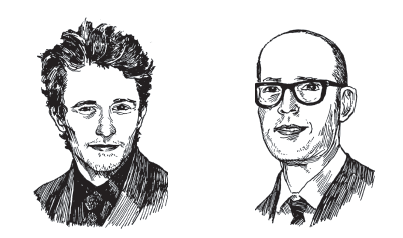

Carter is my double. Whatever I’m thinking, Carter has thought about it, too. He’s a great collaborator because we never argue; we just groove on each other’s ideas. We met at the end of 2007 and did a film in Paris called Erased James Franco. I played James Franco. We did another project with mannequins and mustaches and motorcycles called Double Third Portrait. We wrote and created images for a children’s book called Hellish. He helped me come up with the idea of acting on General Hospital; he helped come up with the idea for Three’s Company as a dramatic movie. We did another film together, Maladies, about us; Catherine Keener plays him. In Maladies the two characters make a pact that if one of them dies the other will finish the dead person’s work. I would be honored to make such a pact with Carter, because he understands me better than most. He has taught me most of what I know about art. Now we’re planning a book of poetry.

—James Franco

I spend a lot of time alone, working in my studio, with a radio and nothing else—making art. I didn’t have much experience or interest in collaborating on creative endeavors with anyone until I started making things with James. I appreciate his zest and drive to work on many things at once and at all times, 24-7. It is inspiring and it is good. Art and more art. Working with James creatively continues to be a special experience for me. I tried erasing him but it looks like I used the wrong side of the pencil. I’ll keep trying.

—Carter

James Franco, Carter, and I met in room 407 at the Bowery Hotel in lower Manhattan. The building is rumored to be haunted, and over the course of our conversation we used a glow-in-the-dark Ouija board to contact spirits and answer interview questions. We wore formal attire, wigs, and sunglasses. The curtains were drawn for a dim séance.

—Ross Simonini

I. “I BE YOUR MUM”

THE BELIEVER: I was talking to one of the bellboys about people’s experiences with hauntings in this hotel, and he told me about all this footage he’d seen from cameras here. Things moving on their own.

JAMES FRANCO: Oh, right. Yeah.

CARTER: Surveillance cameras?

BLVR: Surveillance cameras.

JF: Well, I have to say, I stayed here when we were doing press for Pineapple Express, and I was feeling fine, and then I got into the room, and—didn’t you visit? That was that night!

C: Yeah. We were up at the corner…

JF: I just felt...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in