“The entire world we live in is fabricated.”

—Guillermo del Toro, in an interview with Terry Gross

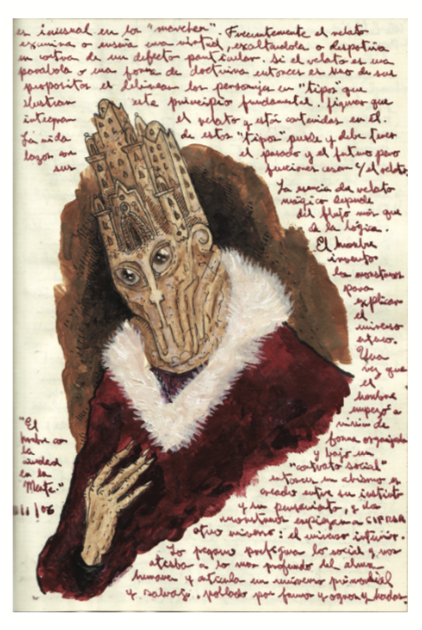

Among the dizzying array of grotesque entities crowding our vision in the Troll Market scene in Hellboy II, a creature in a red velvet fur-trimmed robe flashes briefly across the screen. Over its simian eyes and muzzle sits a miniature cathedral, complete with double towers and decorated archivolts, where a forehead should be. “Originally the idea was to have little humans running around the ramparts,” this creature’s onlie begetter, the movie’s writer/director Guillermo del Toro, cheerfully reported. “But the budget wouldn’t allow it.”

One of about thirty “throwaway” creatures del Toro created for a bravura tableau clearly intended to trump the cantina scene of George Lucas’s first Star Wars film, the monster called Cathedral Head is an emblem of its creator in much the same way the Troll Market sums up the manic whirlwind of a story it’s embedded in. Hellboy II, cowritten, like the first installment, with Mike Mignola from the latter’s graphic-novel series (and aptly dubbed “Pan’s Labyrinth on speed” by one of its producers), expands del Toro’s distinctive vocabulary of images in a baroque explosion of forms commemorated in a coffee-table book, Hellboy II: The Art of the Movie, published to coincide with the film’s release on DVD.

Currently del Toro is contractually committed to a two-movie version of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit; remakes of Frankenstein; Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; and Slaughterhouse-Five; an adaptation of H. P. Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness that he has already drafted a screenplay for; a three-volume vampire novel; and assorted other screenplays and producing gigs. As the forty-four-year-old director embarks on this staggeringly ambitious slate of projects that will keep him busy through the year 2017, it’s instructive to take a closer look at the deeply Gothic worldview that informs his work.

What, exactly, is Gothic? In recent decades the word has been stretched thinner than the cosmetic-surgery addict’s facial skin in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, but historically it describes two separate categories:

(1) What I like to call “Gothick,” the post-Enlightenment popular entertainments (bookended by Horace Walpole’s 1764 The Castle of Otranto and Charles Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer in 1820) that have morphed, through Victorian ghost stories and early twentieth-century pulp and comic-book horror, into today’s plethora of subgenres, including film, video games, “lifestyles,” and even new religious movements, and

(2) The actual historical period of the...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in