Wing Nuts

In books, films, and television, the wing chair has become a shorthand signifier for power, depravity, and corruption.

In Nabokov’s Lolita (1955), rival pedophiles Quilty and Humbert, during their final sleazy face-off, fall into two wing chairs. In Billy Wilder’s film Double Indemnity (1944), Barbara Stanwyck cooks up a plot to kill her husband from one wing chair, then hides a gun beneath the cushion of another. On the reality TV show The Apprentice (2004), real-life tycoon Donald Trump indoctrinates or dispenses with tycoons-in-the-making from his corporatized, boardroom wing chair.

Signs generate meaning, but meaning is not absolute; it changes continually as the relationship between viewer/reader and sign is renegotiated. It is possible, for example, to get a wing chair today without being a real estate tycoon or a corrupt bank CEO. You can purchase your very own Chippendale wing chair for five dollars on eBay or go DIY and make your own with help from the short Howcast.com video How to Make a Cardboard Chair. Regardless of these sweet, democratizing advances, the prevailing meaning of the wing chair in popular culture reflects our need as consumers to have an easy embodiment of our macabre, off-kilter, libidinous, power-mongering drive.

Charles II, crowned king of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1660, could be fingered as the wing chair’s progenitor, insofar as he masterminded the cultural circumstances inspiring the wing chair’s invention and necessity. When Charles II came to power, thereby ushering in the Restoration—a period freed from the Puritans’ censorious moral beliefs toward sex and self-indulgence—his parliament ordered dead Puritan leader Oliver Cromwell’s body exhumed from its resting place in Westminster Abbey, posthumously decapitated, and dumped into a mass grave.1 With Puritanism symbolically dismembered and reburied, the wealthy British populace was finally free to unwind, and needed an appropriate chair in which to do so.

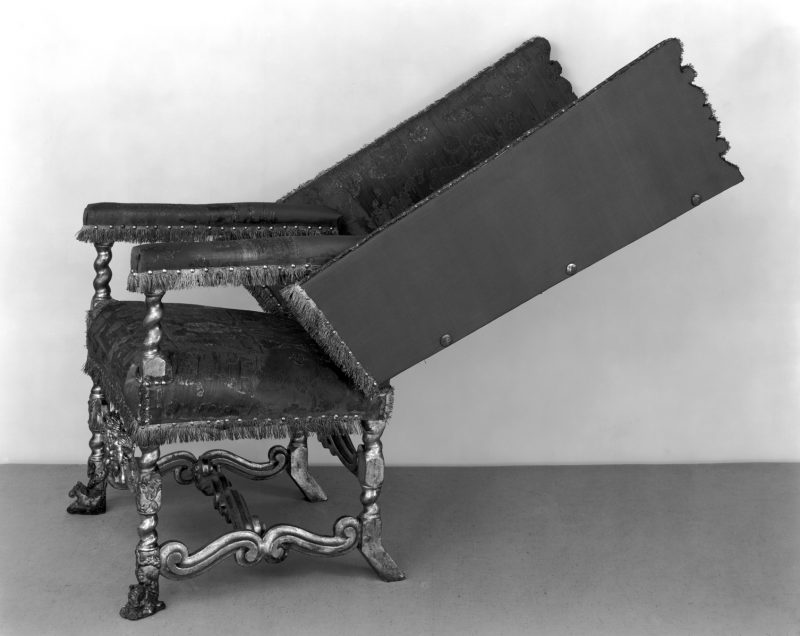

According to Lucy Wood, a senior curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, the wing chair’s direct ancestor was a more obdurate and morose bit of furnishing known as the sleeping chayre, or the reposeing chayre. The two stiff colossal side-pieces of the sleeping chayre cloistered the sitter in a kind of opulent coffin, and were attached to the base by iron ratchets that permitted forward and backward adjustments. (The predecessor to the sleeping chayre was the invalid chair. With its leg supports linked by straps, castors, and rods jutting out from the arms to support a reading desk, the invalid chair looks closer to a medieval stretching rack than to an item designed for convalescing.2)

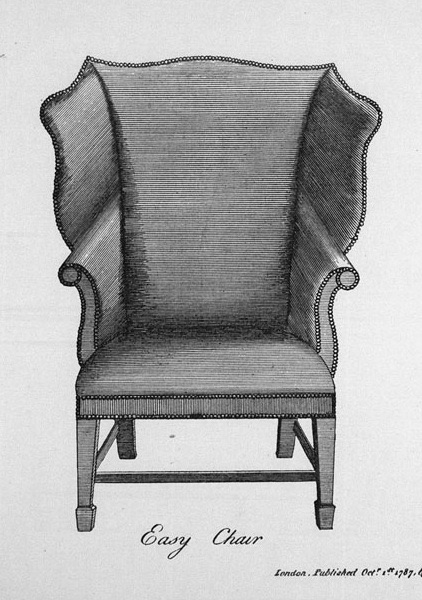

The wing chair, first known as the easy chair, had a high back, low seat, sumptuous upholstery, and side-pieces, known as wings, cheeks, or lugs, to protect the sitter from nasty drafts and other distractions. The earliest example of the wing chair—a stiff and sallow descendant of the sleeping chayre—appeared sometime between 1660 and 1680. Around the year 1700, however, a novel shape was introduced: the curve. Since at least the Venus of Willendorf, a figurine dated around 24,000–22,000 BCE, civilization has idealized the female curve.3 As a symbol of such sensuous stuff, the curve was, unsurprisingly, shunned by the Puritans, people who strove to defeminize what was naturally feminine in women by shrouding them in loose, shape-obscuring smocks. During the Restoration, however, the female form was once again adored and joyfully distorted. Corsetieres were employed to amplify a woman’s breasts and posterior. Whether with a peplum or a pinked-out frill, the backlash against the constraints on sexuality was in full swing, and the wing chair became the libidinous embodiment of the post-Puritan id.

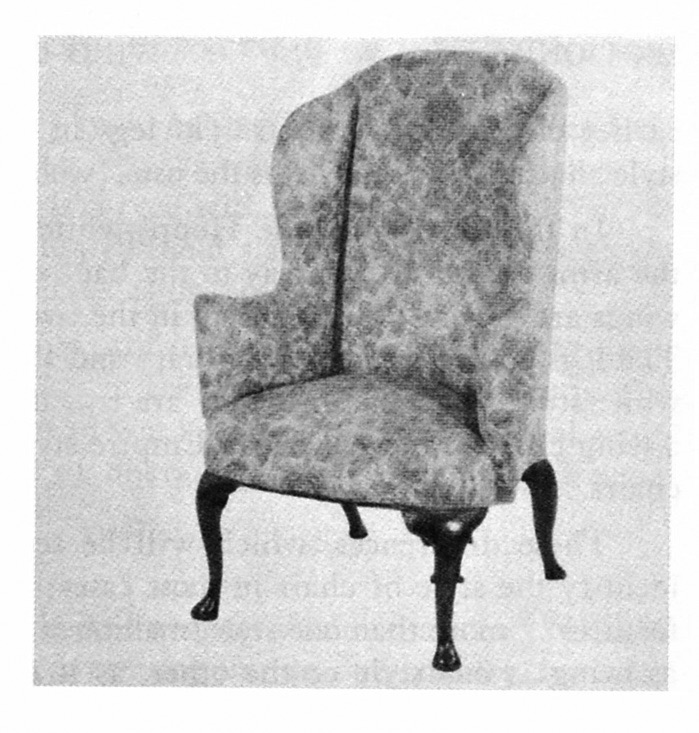

The Queen Anne chair (1702–14), for example, features tiny, delicate Venus of Willendorf–like legs that appear barely up to the task of supporting the voluptuous back and wings. The seat is lower and wider, suggesting that either people were getting fatter or comfort was a higher priority than noble posture. The wing chair was an anthropomorphic goddess chair, providing wealthy men with their own private vulvas to nestle in while nursing expensive claret or taking snuff from lacquered boxes, unaware that they were commencing a phase of moral deterioration from which they would never emerge. In The Englishman’s Chair: Its Origins, Design and Social History (1964), modern furniture historian John Gloag observes:

This traditional association of chairs with an upright, dignified bearing was not overcome until the late seventeenth century when the easy chair was invented, and though nobody at the time suspected what this invention would do to good manners, it was the starting point of a slow but continuous decline of dignity.

The Golden Age of Ticklingburgs

The emergence, in the 1770s, of a vast new middle class of wealthy merchants, traders, inventors, bankers, and brewers resulted in the replacement of social-based relationships with objective affiliations between commodities and currency.4 As a result, people were reduced to commodities themselves, valuing each other based on the amount of property owned, artifacts acquired, and good taste demonstrated.

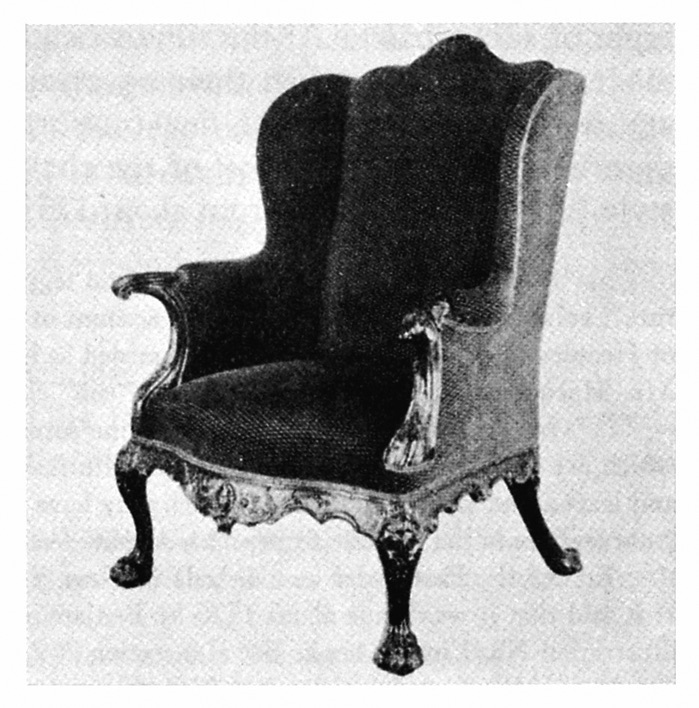

Within this paradigm, the owner of a wing chair could further exhibit her financial and social status by the upholstery she chose for her chair, whether it was “Ticklingburgs,” “Oznabrigs,” or “Pomerania Linnens.” The Chippendale period (1740–85) saw carvers embellish a knee with a shell, acanthus leaf, or swag of flowers.

But manual labor in the textiles industry was steadily being replaced by machine-based manufacture, and it wasn’t long before the chair, too, was affected by technological invention. The practice of buttoning (fastening buttons to the upholstery of the chair), which emerged in the second half of the eighteenth century, amplified the wing chair’s curves and breadth, further reflecting the excesses of the upper classes.

The late eighteenth century—a period devoid of intellectual quality and moral stability—became characterized by contempt for hard work and the desire to get rich quick. The financial disparity between the classes caused much animosity. Rural workers moved to cities in search of low-wage industrial jobs, but lack of employment led to a high incidence of theft, street assaults, and highway robbery. It didn’t help that excessive gin drinking was now a national vice in England.5

The dead and drunken bodies in city streets mirrored the bodies, drunken and unconscious, after parties in luxurious city drawing rooms. William Hogarth painted a series of satirical attacks on the upper classes, marriages of convenience, gin drinking, and the avarice and vulgarity of fashionable life in the eighteenth century. Marriage-à-la-Mode: 4, “The Toilette” (1743) shows a party in full swing, men lounging obstreperously on the arms of cushy wing chairs, cards tossed on the floor, and women sitting with their elbows hanging over the backs of seats. If physical posture is any indication of moral fiber and self-esteem, these city slickers had a lot less pride and dignity than their predecessors.

A Seat for Your Saddlebags

As manners continued to decline, the wing chair sunk to new levels of weight, bloat, and extravagance. The Hepplewhite (1785) and Sheraton (1795) styles, overstuffed, swaggering, and obnoxious, embodied the heightened embrace of luxury as merchants and industrialists amassed more wealth. The wings of the Hepplewhite were so oversize they resembled the sides of a saddle, hence the chair’s alternate name, the “Saddle Check.”

With the invention of the coiled spring, in 1828, originally patented to prevent seasickness, the chair became wider and more squat, and its legs shorter, which served well to accommodate the heavy silks and stays under women’s skirts.

Despite the wing chair’s popularity, historians at the time made note of the not-so-subtle influence of the chair on the comportment of the seated. In a book on manners published in 1842, Captain Orlando Sabertash denounced the practice of “lounging in graceless attitudes on sofas and armchairs,” calling it a breach of proprieties. He advised women to give the “cut-direct” to any man found lounging in their presence, and go to another part of the room to retaliate for the “vulgar and uncivil” behavior. Lady Barker, in her nineteenth-century handbook The Bedroom and Boudoir, rejected the “fat and dumpy modern [wing] chair.” In his book Furniture Treasury (1948), historian Wallace Nutting observes that designs during this time had become “finicky… frail, over-luxurious, trivial, and hastening to depravity.” He further noted that by the late nineteenth century, hand-crafted furniture was being replaced by cheaply manufactured goods and claimed, “This system is subversive of character. Everything below the surface is rotten—if not the wood, the method…. It is the murder of the finer attributes.”

Meanwhile, the wing chair crossed the ocean to the United States. The late nineteenth century created magnates of American industry such as Cornelius Vanderbilt (shipping and railroads), John D. Rockefeller (oil), E. I. Du Pont (chemicals), and William Randolph Hearst (publishing), collectively known as the robber barons. This so-called “Gilded Age” provided another ripe social context for wing-chair-as-status-symbol propagation. The wing chair made history in 1929 when a chair in the French Chippendale style, made in 1770, sold at the Reifsnyder Auction in New York for thirty-three thousand dollars, the highest price ever paid, at that time, for an American chair at auction. The event, attended by Hearst and Du Pont, proved that the wing chair held sway with the rich and powerful men of twentieth-century industry, even on the eve of the world’s most dire economic collapse.

During the Depression, wing-chair production fell precipitously. Materials were scarce; the social atmosphere was not one of resplendent indulgence but one of thrift. “In the interwar years,” said Gareth Williams, curator in the Department of Furniture, Textiles and Fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum, “modernist furniture designers neglected the form, preferring smaller and more portable chairs.”

But immediately after World War II, the wing chair returned with a vengeance and a fiercer, slicker look, as illustrated by Ernest Race’s 1946 chair, the DA1. This was not the plush, forgiving chair of Hogarth’s wanton partygoers, but an ultramodern, lightweight update. Other contemporary designers such as Jurgen Bey, and the Swedish company Lyx, transformed the wing chair to convey the casual futurism of mid-century life. The huge geometric wings of Bey’s Ear Chair call for extreme privacy; matching tables enable business employees to sip tea or hold meetings in a comfortably informal setting.

Lyx’s Wing Lounge Chair, upholstered in open-cell visco-elastic memory foam (developed by NASA), adapts to the shape and temperature of the sitter’s body, taking comfort to new dimensions. The Lyx chair not only does away with formality, it allows the sitter to lose all sense of her physical body. While there was an incidental loss of ceremony, the chair has maintained its aura of importance. A Lyx chair, designed for “special” customers, is available to the small fraction of the population that can afford it. No matter how updated or space-age, the wing chair continued its elitist streak.

Decay-Inducing Curvature

Given its enduring position as a status symbol, the wing chair was employed not only by painters but also by writers and, eventually, filmmakers to convey or comment on notions of wealth, status, and degeneracy. Quilty, for example, alights from a wing chair in the film adaptation of Lolita (1962), and offers Humbert a game of Roman ping-pong before he is shot. In The Godfather (1972), Michael, godfather-to-be, is indoctrinated by his Cosa Nostra elders while seated in a wing chair.

But perhaps the most self-referential example of the use of a wing chair occurs in the film Citizen Kane (1941), a fictionalized story based on the life of William Randolph Hearst. Like Hearst, Charles Foster Kane was the early twentieth century’s answer to the governing lords of the seventeenth century. Kane is the tycoon capitalist, the commodity fetishist. In a pivotal scene, Kane’s wife is furious that he’s allowed a negative review about her operatic performance to be published in one of his newspapers. The newspapers are scattered about, some on the floor and some, symbolically, on the seat of the wing chair—the throne of cultural power.

The ’60s saw the filmic use of the wing chair in a more self-conscious and hypersexualized way.6 It became the seat of villains, most memorably James Bond’s archenemy, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, who swivels around in his black leather wing chair while stroking a white Persian cat in You Only Live Twice (1967). In Goldfinger (1964), the evil genius Goldfinger’s jet, flown by Pussy Galore and her Flying Circus, is outfitted with wing chairs. In Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me (1999), not only does the foe, Dr. Evil, sit in a futuristic electric wing chair, his evil mascot and literal id representative, Mini-Me, sits in a matching small-fry variety. But Dr. Evil’s futuristic wing chair malfunctions erratically, spinning around like a top. It is no longer just the sitter but the chair that’s out of control. The chair and the loon have become one and the same.7

The wing chair is represented in literature in much the same way as it is in film—as a receptacle for rich, deranged, physically ill, dangerously powerful, and/or corrupt people or those in a situation that is just slightly off. As an example of the ubiquity and breadth of the usage of the wing chair in novels, short stories, and plays, I offer the following non-exhaustive list:

Middlemarch, George Eliot (1874); Hedda Gabler, Henrik Ibsen (1890); Pygmalion, Bernhard Shaw (1913); Main Street and Babbit, Sinclair Lewis (1920 and 1922, respectively); To a God Unknown, John Steinbeck (1933); Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison (1952); “O Youth and Beauty!,” John Cheever (1953); Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov (1955); Goodbye Columbus, Philip Roth (1959); Rabbit, Run, John Updike (1960); In Patagonia, Bruce Chatwin (1977); Amadeus, Peter Schaffer (1981); The Musical Comedy of Murders of 1940, John Bishop (1987); The Savage Detectives, Roberto Bolaño (1998); My Century, Günter Grass (1999); “Octet,” David Foster Wallace (1999); The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Improving Your Memory, Michael Kurland (1999); In America, Susan Sontag (2001); Germs: Biological Weapons and America’s Secret War, Judith Miller, Stephen Engelberg, and William J. Broad (2001), which reports that even Bill Clinton enjoyed sitting in a wing chair by a fire under a portrait of George Washington; Devotion, Adam Haslett (2002); Book of Illusions, Paul Auster (2002); The Nanny Diaries, Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus (2002); Running with Scissors, Augusten Burroughs (2002); Florida, Christine Schutt (2003); Haunted, Chuck Palahniuk (2005); Terrorist, John Updike (2006).

But the wing chair as a symbol of decadence, power, debility, and offness indisputably crests with Thomas Bernhard’s novel Woodcutters (1984), a seething diatribe against Austria’s beau monde. Bernhard introduces the wing chair, with all its decay-inducing curvature, as the seat of the narrator, who is attending a lavish artistic dinner with all of Austria’s café society in attendance. The hosts are a wealthy, powerful couple, the Auersbergers. The narrator is seated in his wing chair in a dark adjoining room, watching the other partygoers enter and exit, and tearing them apart with sadistic zeal:

For twenty years I had not seen the Auersbergers, and in these twenty years the very mention of the name Auersberger had brought on third-degree nausea, I thought, sitting in the wing chair.

Perfidious society masturbators—what an apt description! I thought, sitting in the wing chair.…

And so on. In the novel’s first hundred pages, during which the narrator is still seated in the wing chair, the phrase wing chair is used 218 times.

Early on, we get the sense that the narrator is not quite right in mind or body. He has a lung illness, and is profoundly hopeless and desperate, aligning himself with other wing-chair sitters/owners like Burns and Kane as well as resonating with the chair’s roots as a transporter of invalids. The fact that he has come to a party to sit in the dark and eviscerate people is proof enough that he is one disturbed wallflower.

Once again, the bourgeois lifestyle is the scapegoat. The narrator blames his hosts, the Auersbergers, for his current condition, for having lured him when he was a poor young artist, thirty years earlier, into their wealthy bourgeois lifestyle, daytripping to local castles, and weekending at their estate with vaulted ceilings, well-stocked cellars, and libraries. It was the introduction to their customs, and the instantaneous access to and love of their possessions, that led, he claims, to an erosion of his character, which culminated in an “existential crisis” and landed him in the Steinhof mental clinic.

But the narrator does not end at the connection between bourgeois lifestyle and mental/physical debility. There is an inherent sense that everyone at the party is living a borrowed life, in this case as a result of having traded in their artistic integrity and originality for wealth and recognition. Rather than becoming original talents, which they had at once aspired to be, Austria’s most prominent female writers, having been won over by state prizes and pensions, are now no more than the country’s answer to Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein. Like seventeenth-century merchants, these bourgeois artists are noble frauds.

The narrator of Woodcutters is a modern-day Karl Marx, whose aim it is to unmask the relationship between producer and consumer, in this case Austria and its complacent artists, respectively. As Marx saw the producer/consumer relationship as one enshrouded in a dense fog of social and political ignorance, so, too, does Bernhard’s narrator view the relationship between Austria and its artists as an association in need of demystification. The narrator aims to reveal the connection between the two parties, and homes in on the active role that Austria played in the mollification and subduing of its artists. He proposes that the objectification of human relationships can and has produced far greater consequences than merely living a rich and boring life:

The Austrian stomach is pretty strong. The Austrians in general have strong stomachs, considering what an awful tasteless history they’ve had to gulp down over the years.

The narrator here refers obliquely to another situation in which the conformist behavior of individuals to the establishment, and the detachment between the state and its members, permitted the occurrence of atrocities that still haunt the current culture. He calls the party a “funeral feast” and continues to allude to its necrologic atmosphere. The partygoers, who refuse to face their nation’s history, which he thinks is their duty as artists, are “the living dead of the artistic world.”

But it isn’t until the narrator enters the music room that the furniture, and specifically the wing chair, is revealed to be a microcosm of this greater illness. The furnishings, all from a bygone era, represent the inability of the partygoers to live in the present and their nostalgic attachment to “the softness of the dead past that cannot answer back.” The wing chair becomes an emblem not only of death but of the pretense exhibited by the Auersbergers, and equates the Auersbergers with their objects: “It’s not only the emperor’s clothes that make the emperor, but the emperor’s furniture and art treasures….”

The narrator is not unaware that he is falling back into the trap of the Auersbergers, but he rather enjoys the privilege of their borrowed goods:

I’ve always pretended to them about everything—I’ve pretended to everybody about everything. My whole life has been a pretense, I told myself in the wing chair—the life I live isn’t real, it’s a simulated life, a simulated existence.

And when he says of Vienna, “This is my city and always will be my city, these are my people and always will be my people,” it is clear that the wing chair’s commodious berth has baited yet another victim.

An Enduring Legacy

The wing chair shows us something ugly in ourselves that we are both repelled and riveted by. “Our products would be so many mirrors in which we saw reflected our essential nature,” says Marx in his Comments on James Mill. Chairs, at least the wing chair, as illustrated by the Lyx Wing Lounge, have become increasingly restful; as a culture we prize comfort. But have we lost dignity? Does Barack Obama look undignified, louche, or lacking in good judgment when he’s photographed seated in a wing chair consulting with Valerie Jarrett? Hardly. Not everyone who sits in a wing chair is a doomed sitter; at least not in the world outside of cultural representation.

Many tycoons and wing-chair sitters of today are being publicly shamed (or economically forced) into becoming less materialistic citizens. Even Donald Trump appears critical of the pointless hoarding of objects. In Errol Morris’s aborted film The Movie Movie (2006), The Donald says:

Citizen Kane was really about accumulation, and at the end of the accumulation you see what happens. And it’s not necessarily all positive, not positive…. You learn in Kane that wealth isn’t everything, because he had the wealth but he didn’t have the happiness.

But then again, if given the chance to offer Charles Kane advice, The Donald responds, “Get yourself a different woman.”