I. What Is Success?

The night of Barack Obama’s victory, eighty-six-year-old cartoonist Bil Keane called his old friend Morrie Turner, himself a sprightly eighty-four. Turner was working on his strip Wee Pals in the office of his tiny bungalow in South Berkeley, leaning over his drafting desk, its surface worn to the curve of the wood grain, tracing and embellishing the pencil outlines in India ink on Bristol board. A Law & Order rerun played in the background. Inking a strip to the natter of a TV program: for Turner, these were familiar rhythms, warm comfort for forty-three years. At that moment, the last thing he wanted to hear was the news.

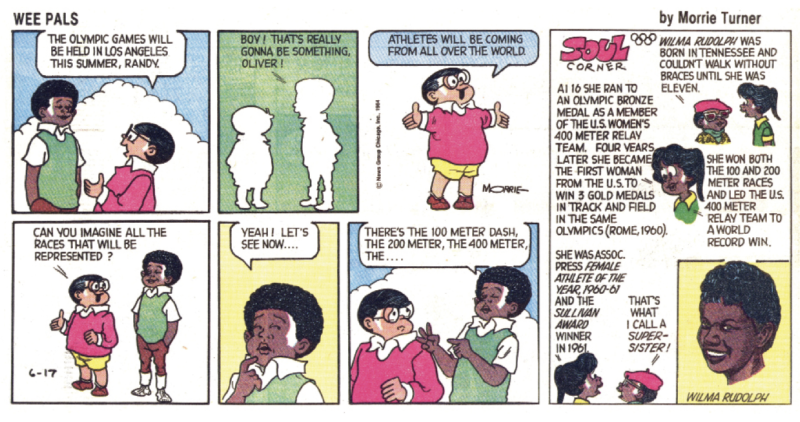

Keane’s strip, Family Circus, had launched in 1960, one year before Obama was born. In it, Keane drew the antics of his suburban children in a single round panel, each installment like a portrait-miniature of the white boomer wonder years. Five years later—days before Malcolm X was assassinated, months before the Voting Rights Act was signed and Watts burned—Wee Pals debuted. Turner’s strip simply presented an urban, multiracial group of kids figuring out how to get along, but nothing like it had ever been seen on the funny pages. The launch of Wee Pals made Morrie Turner the first nationally syndicated African American cartoonist.

Keane and Turner had formed their close bond in 1967 as pacifist World War II vets on a USO trip to Vietnam. Keane would introduce a black boy named Morrie into Family Circus, just about the same time Charles Schulz added Franklin to Peanuts.1 Both were tributes to Turner. On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Cities were on fire. Blackness was suddenly in demand. Wee Pals went from six newspapers to more than a hundred. For Turner, success was bittersweet. Privately, he would say that it was guilt that got him into the papers.

Wee Pals belonged to a quieter, less violent universe. Even in the worst of times, Turner labored on, certain that it was the country that needed to come around to his kids’ world, not the other way around. Was Obama’s candidacy a sign that day was finally coming to pass? People had begun using a strange word—“post-racial.” Did it mean racism was over? Or just images of racism? Was the word just another form of denial?

Turner had told friends he was happy that Barack Obama was running, but he was terrified Obama would be killed while trying. And now on...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in