1.

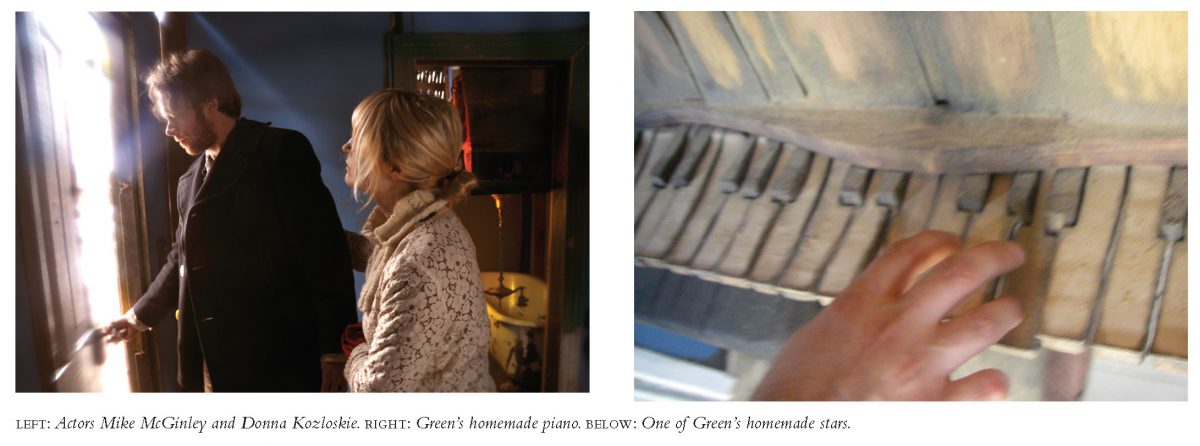

The animated shorts of Brent Green have played at a variety of venues: in film festivals like Sundance, in museums like the Hammer in L.A., in bars with both Green and a band providing a live soundtrack. Self-taught in his artistic pursuits and collaboratively minded, Green has always made things by hand. His aesthetic privileges imperfection over slickness. The tape holding together his animation cels, for example, is often visible; the light changes dramatically between frames. In Hadacol Christmas (2005) and Paulina Hollers (2006), Green used his signature handmade puppets and animated pen-and-ink drawings. With Carlin (2007) he got “big,” using a life-size puppet, a real wheelchair, and real birds and bees. Tinkerer Used to Be a Trade (2009) incorporates a person for the first time (Green’s girlfriend, Donna Kozloskie); she’s placed in minutely adjusted positions for each individual frame, treated as though she were a 2-D animation.

In addition to Green’s narration, supplemental audio support is provided by various talented musician friends, including Califone, Brendan Canty, and Howe Gelb.

Echoing this homegrown spirit, Green recently erected, on his family’s land, an actual town in which to shoot his first feature film, Gravity Was Everywhere Back Then. Last July, I went to see this town. I flew into a large city, took a train to an old stop, and drove over rolling hills until I arrived at the refurbished barn where Brent and Kozloskie live. Beside the barn is Green’s childhood home, still damaged from a fire that burned years ago.

2.

The first thing you notice about Green’s backyard isn’t the buildings, but a network of poles and wires, along with various ropes and pulleys, used to suspend the wooden stars that shine over the new town. (All of the lights inside the stars are attached to separate dimmers so that Green can control the twinkle.) A giant dark cloth can be drawn around the perimeter to black out the rest of the world. At night, it’s pretty damn gorgeous.

Five houses surround a central dirt “main street.” The houses are actually quite sturdy, built from the salvaged wood from two derelict barns on the property. The more I look at the buildings, the more I start to notice odd touches: not-quite-right angles, things leaning where they shouldn’t, windows that are almost square. The sets don’t look built so much as they seem scripted.

Four of the houses are two-story-tall facades, with working doors and windows. One house—in which most of the film takes place—is almost livable. It has electricity, walls, a living room, a kitchen, a bedroom, and a toilet (but no...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in