Before he became the husband of Adeline Virginia Stephen—later a novelist of some considerable reputation—Leonard Woolf was a cadet in the Ceylon Civil Service. At Cambridge, Woolf had been a member of the Apostles, the exclusive secret society that also included John Maynard Keynes and the philosopher G. E. Moore. But he didn’t graduate from Cambridge with any particular distinction, and unlike his peers he didn’t have very much money: he was one of nine children, and his father, a Queen’s Counsel, had died when he was eleven, of tuberculosis and workaholism. Woolf couldn’t afford to read for the bar himself—the registration fee alone was forty pounds—and he wasn’t especially confident that, as a Jew and an atheist, he was cut out for school teaching, which would have been the other conventional option. So in 1904 he took the British civil service examination. He placed sixty-ninth out of ninety-nine.

That wasn’t good. But it was good enough to get him a second-rate position: an Eastern Cadetship in the Colonial Service. He packed up his clothes and the complete works of Voltaire in ninety volumes and steamed off over the horizon, bound for Colombo, then the capital of Ceylon, aboard the SS Syria of the P&O line. The journey would take a month. Because the P&O line wouldn’t carry dogs, Woolf’s faithful wire-haired terrier, Charles, had to come by a separate boat.

At twenty-four, Woolf was both world-wearily cosmopolitan and touchingly innocent. As was the fashion among the Apostles, he was a misanthrope and a committed cynic—his personal motto was “Nothing matters.” He was proud and touchy and sharp-tongued. He was also exceptionally brilliant; by the time he was a senior in high school he was already a first-rate classicist. (His poor showing in the civil service exam was the result of spotty preparation, not a lack of brainpower.) But Woolf was also a virgin who had never traveled farther from home than northern France. He was nowhere near as jaded as he liked to pretend. Fifty-five years later he would write in his second volume of autobiography, Growing, that when he waved good-bye to his mother and sister on the London docks that morning, it felt like a second birth.

Ceylon was a giant step forward into adulthood and independence for Woolf, but it was also a great leap backward—backward in time. Ceylon had yet to enter the twentieth century, at least as it was known in the Western world. “Before the days of the motor-car,” Woolf wrote, “Colombo was a real Eastern city, swarming with human beings and flies, the streets full of flitting rickshas and creaking bullock carts, hot and heavy with the complicated smells of men and beasts and dung and oil and food and fruit and spice.” The alien heat and gargantuan insects appalled Woolf. The day after he arrived he was reunited with Charles at the docks. Charles promptly peed on a passerby, who seemed not at all troubled by this, then threw up from the emotion and the sun. Crows flew down to eat the vomit. Welcome to Ceylon.

Woolf’s first posting was to Jaffna, a town at the very northern tip of the island. Arriving in January, he immediately set about learning Tamil and acquainting himself with the local legal code. It would have been easy for his colleagues to underestimate Woolf. He was slightly built and cursed with an unintentionally comical appearance: he had a long face, jug ears, and an enormous caricature of a Jewish nose. But there was a steely mental toughness to him. At first his responsibilities were largely bureaucratic, but he complained to his superiors that he was bored, and over the course of his career his job would eventually be broadened to include everything from overseeing agricultural projects to investigating murders. Touring the outskirts of his district, he would sometimes bicycle thirty-five miles in a day. He discovered that he had a mania for efficiency. At Cambridge, Woolf and his friends had evolved something they called “the method,” a kind of marathon interrogation technique that they used to break people down, take their measure, and expose their weaknesses. Woolf adapted “the method” for use in colonial bureaucracy—one of his innovations was the practice of answering every letter on the same day it was received. This dramatically improved his office’s productivity while at the same time provoking his subordinates, who were mostly Ceylonese clerks, to the brink of mutiny.

After work came the colonial sacraments of tennis and bridge and tea and whiskey. It was the twilight of the imperial world of Kipling. The white population of Jaffna consisted of maybe two dozen people, a gossipy little cell that distrusted Woolf’s intellectual airs, which he quickly learned to conceal (the Voltaire, he later recalled, was “a particular liability”). Needless to say, the social life wasn’t everything Woolf could have wished for. “Lord!” he wrote to his best friend and fellow Apostle Lytton Strachey, who was safe at home in England, having done even worse than Woolf on the civil service exam. “I’m damnably polite and nice and quiet but I feel at any moment I may get up and burst out against the whole stupid degraded circle of degenerates and imbeciles.”

Woolf was an assiduous observer of human fauna, and an equally assiduous autobiographer, and it’s possible even now to reconstitute the social structure of white Jaffna in near-molecular detail from his letters and memoirs. The molecule on which Woolf lavished the most attention, after himself, was Jaffna’s police magistrate and the town’s other would-be intellectual, a man named B. J. Dutton.

Most of Woolf’s colleagues could at least pass for gentlemen, but Dutton couldn’t. He wasn’t a “pukka Sahib,” in the parlance. He hadn’t been to university, and his background was lower-middle-class. He didn’t play tennis or bridge. Woolf described him as “a small, insignificant-looking man, with hollow cheeks, a rather grubby yellow face, an apologetic moustache, and frightened or worried eyes behind strong spectacles.” He was nervous and socially awkward. He lived alone “in a largish bungalow with a piano, so it was said, and a vast number of books.”

The other policemen hated Dutton. “A bloody unwashed Board School bugger, who doesn’t know one end of a woman from the other” was how he was described to Woolf. But Woolf didn’t hate Dutton. He was just baffled by him. And, despite himself, fascinated by him. That spring—May of 1905—Woolf found himself in need of a new place to live. Even though he knew his reputation would take a major hit, he moved into the largish bungalow along with the piano and the books and Dutton.

There the two men gradually got to know each other. Dutton was terrified of his peers but also considered them contemptible—vulgar and cruel and uneducated. He mooned over women, but the idea of actual sex repulsed him; it would be “impossible with anyone with whom one was in love.” Nevertheless, Dutton was a kind man, and he had a gallant streak. In one case, when a prostitute was brought before him for sentencing, Dutton convicted her, but paid her fine himself and gave her client a stern talking-to. (Everybody else thought that this was incredibly funny, including Woolf, who was one of the girl’s clients—in fact, he had surrendered his virginity to her.) “I have hardly ever known anyone so hopelessly incompetent as Dutton was to deal with life,” he wrote. “He lived the life of a minnow in a shoal of pike.”

Like Woolf, Dutton had literary aspirations. His bungalow was indeed entirely lined with books—cheap editions of the classics intended for popular improvement—and he spent every evening writing poetry; he’d amassed hundreds of thousands of lines of it. His verses were, in Woolf’s opinion, “incredibly feeble.” Woolf wasn’t a cruel man, but he had after all been an Apostle, and he was a literary snob of the first water. The intensity of the revulsion he felt at reading Dutton’s poetry took him to metaphorical extremes:

When later on in Ceylon I became an extremely incompetent shooter of big game, and, in cutting up the animals killed by me, saw the disgusting, semi-digested contents of their upper intestines, I was always reminded of the contents of Dutton’s mind. As he not unnaturally disliked and temperamentally was frightened of the people and life which surrounded him, he very early escaped from them and it into books and the undigested, sticky mess of “culture” which they provided for him.

What Woolf saw on the onionskin that had passed through Dutton’s decrepit typewriter left him literally incredulous. “Who could possibly imagine,” he wrote, “that in 1905 an English civil servant, a Police Magistrate—what we now know to have been an imperialist—would sit hour after hour, day after day, writing poetry about fairies or, as he called them, fays?”

*

We know a lot about Woolf. He couldn’t have realized it then (though he probably had his suspicions), but his destiny lay with the inner circle of the ruling literary caste of the twentieth century. He was a harbinger of modernism, the school of Virginia Woolf and Joyce and Faulkner and Hemingway. But who was B. J. Dutton? There was no word for him in 1905, but we have one now: he was a nerd avant la lettre. And he was a harbinger, too, in his tiny, ineffectual way, of another of the twentieth century’s dominant literary traditions: fantasy.

So far as I can tell, Woolf scholarship, at least of the Leonard variety, has until now remained innocent of Dutton’s full name, probably because nobody ever bothered to look him up. But he is eminently findable, even by an amateur literary sleuth. Woolf remarks in Growing that Dutton was four years older than he was. Woolf was born in 1880. Public records show many Duttons born in England in the 1870s, but only a handful of male Duttons, first initial B. And there is only one B. J.: Bernard Joseph Dutton, born 1876, bang on time, in Stoke on Trent. He is beyond a doubt, for reasons that will become clear, our B. J.

The 1881 census found Bernard at age five living in Whitford with his parents: Aaron Dutton, “boot dealer,” and Anne Dutton, “wife of boot dealer.” He was the oldest of four brothers. The 1891 census has him as a student at a Catholic boarding school near Stoke on Trent called Cotton College; Aaron is by this time the foreman at an enamel works in Burslem, and father to yet another son and two more daughters. Bernard Joseph Dutton is absent from the 1901 census, but he reappears, as Mr. B.J. Dutton, on the passenger list of the Staffordshire, a steamship that left Liverpool for Colombo on April 14, 1904.

Something strange passed between Woolf and Dutton in that bungalow. Later in life Woolf would become a good Freudian (as steward of the Hogarth Press, he would be Freud’s first publisher of record in England). If he’d been one in 1905—and if Freud had invented it yet—Woolf might have found his theory of the unheimlich, the uncanny, useful in understanding his feelings about Dutton. Freud explained this theory (which he didn’t come up with until 1919) using an anecdote about an experience he had on a train. A man walked into the compartment Freud was traveling in. Freud instinctively disliked him—“what a shabby-looking schoolmaster” was his internal comment. A second later Freud realized that he recognized the man: the man was Freud. A bathroom door had swung open, and Freud was looking at his own reflection in a mirror. He identified that unsettling, mystical, electrical sense of simultaneous recognition and revulsion as “the uncanny.”

When Woolf met Dutton, the bathroom door swung open. Dutton was a mirror image of Woolf, both attractive and repellent, strange and strangely familiar at the same time. As his excellent biographer, Victoria Glendinning, puts it, when Woolf looked at Dutton he saw “a terrifyingly degraded version of himself.” Both men were outsiders, of uncertain social standing, sexually inexperienced, who nourished secret dreams of literary glory. Woolf too felt contempt for those around him—he was afflicted with a mild congenital tremor in his hands that Virginia Woolf later recalled seemed to express her husband’s barely contained loathing for humanity. Leonard himself compared Dutton to another Leonard: Leonard Bast, the working-class intellectual in Howards End. Dutton was a Woolf in sheep’s clothing.

And there were those poems, Dutton’s feeble fays. If they’d been just bad Woolf might have felt dismay or embarrassment. But Dutton’s writing wasn’t just bad. Woolf actually found it disgusting. Frightening, even. Like those dead entrails, heavy with food halfway on its way to becoming fecal matter, both filthy and fertile, Dutton was abject. He produced in Woolf a special kind of fear, the kind provoked by something horrible and infectious that implicates not only the other, but oneself.

In a weird way, Dutton’s poetry couldn’t have been better calculated to prey on Woolf’s buried anxieties. Both men were engaged in the work of Empire, vigorously superimposing a tidy bureaucratic English order on what to them was a primal and chaotic Tamil folk culture. By writing about magic and fairies Dutton was poking around in the shallow grave of England’s own folk culture of magic and fairies. He was blurring the tidy line that was supposed to separate the colonizers from the colonized. To Woolf, fantasy must have seemed like a kind of treason, a betrayal of their shared allegiance to the modern era. If an Englishman can believe in fairies, how the hell can you tell him apart from the savages? The whole system comes crashing down! “If we have a tree in our back garden, there is no devil, no Yakko in it,” Woolf wrote in Growing. But, he added, dropping his voice to a stylistic whisper, “very deep down under the surface of the northern European the beliefs and desires and passions of primitive man still exist, ready to burst out with catastrophic violence if, under prolonged pressure, social controls and inhibitions give way.” In Dutton, Woolf smelled a literary Kurtz, in imminent danger of going native. (And lest we forget, Woolf was only two generations removed from the Jewish tailors of London’s East End. He and his family were busily engaged in erasing any traces of their own indigenous culture, in an effort to attain some semblance of English respectability. At Cambridge he’d been almost as exotic to his fellow undergraduates as the Tamils of Jaffna were to him.)

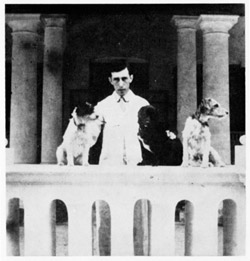

Just as every Englishman has a savage somewhere inside him, watching and waiting for a chance to tear his way out, every adult has a child inside him, and in Woolf’s case that child wasn’t very far below the surface. At twenty-four Woolf was not yet completely grown up. He was always waxing lyrical about his childhood, the time before his father’s death, which he remembered as “the Platonic idea laid up in heaven of security and peace and civilization.” Now he was barely out of college and clinging tenuously to adulthood, plugging his ears against the siren song of the nursery while trying to assert his authority in a strange land over men two and three times his age. There is an absolutely priceless photo of Woolf in Jaffna on a balcony in formal dress, with his hounds all around him, playing the role of the Western lordling and managing to look all of about fourteen years old. Dutton, a man who looked like a child, and who wrote about childish things, would have seemed to Woolf like a cruel parody of himself, a living image of the self he was seriously worried that he truly was.

But who was Dutton, really? Was he just a virginal boy-man who wouldn’t grow up and put aside childish things? (Peter Pan, the epitome of this particular late-Victorian obsession, opened to massive acclaim in December of 1904, the very month Woolf arrived in Ceylon.) Granted, to a lot of people, Duttons and Woolfs alike, fantasy is the literature of childhood. Our reading lives don’t begin on Earth, they begin in fairyland, or Middle-earth, or Narnia, or Earthsea, or Hogwarts; for Woolf it might have been Wonderland, or George MacDonald’s faery dreamlands, or the weird aquatic netherworld of Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies. We know that at boarding school Woolf was a rabid consumer of early science fiction—he wrote about drowsing under the gas jets in the school library and being “transported from the rather boring and always uncertain life to which one had been arbitrarily and inexplicably committed, to the strangest, most beautiful, and entrancing world of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, or The Log of the Flying Fish.” (The latter is a long-forgotten novel about the voyages of a magnificent ship made of atherium, a material so strong it can travel underwater, and so light it can fly.)

It’s odd that children are so interested in fantasy when they’re still in a position to find the real world fresh and new. You’d think we’d raise them on Dreiser—they, unlike most people, might actually be curious about the gritty, naturalistic details of the life of Sister Carrie. It’s possible that to children the world still appears to be mysterious and inexplicable and occasionally monstrous and thus best represented by narratives about the supernatural. It’s also possible that, being closer to infancy, they haven’t entirely shed a vision of a world that is not boring and uncertain, arbitrary and inexplicable—that is not indifferent to their needs, a world in which they are powerful, central figures. It has not yet been definitively demonstrated to them that their thoughts and words cannot alter the universe. Freud had an appropriately fantastical name for this childish delusion: he called it magical thinking.

Magical thinking isn’t fantasy in the literary sense. It is a fantasy, in the psychoanalytic sense: a dream of a world where actions don’t have consequences, where loss is an impossibility, where wishing makes it so, where one doesn’t have to make choices, because all possible good things arrive at once, unbidden, with none of those nasty trade-offs that are so characteristic of real life. There is no either/or in a fantasy, it’s all both/and. This is the world that Dutton’s fairies evoked for Woolf, and that he was struggling so mightily to put behind him.

But fantasies aren’t literature, and fantasies aren’t fantasy. This isn’t a distinction that Woolf would have made, but Dutton might have made it. Granted, fantasy literature, broadly speaking, tends to be set in worlds where magic is real. But that doesn’t mean anything is possible. Magic doesn’t permeate those worlds completely. Magic exists, but only as a flash of vital light in a universe that is otherwise as dark and mechanical as our own—its presence casts the tragic, non-magical parts of life in higher relief. Magic tantalizes with the possibility that it might quicken the world back into life, restore the lost paradise of magical thinking, but ultimately it cannot.

The non-fan’s idea of fantasy is like the Land of Do-As-You-Please in Enid Blyton’s The Magic Faraway Tree, where children can drive trains and ride elephants and eat six ice creams at one sitting whenever they want to. But a much better example is Tolkien’s Middle-earth: the Elves live there, and do not age or die, but mankind lives there, too. The two races, mortal and im-, coexist within a single cosmic continuum, and you’ll never feel your mortality more keenly than when you’re standing next to a death-proof elf. (Elves lose their immortality if they mate with a human, a deal it’s hard to imagine any competent elf striking.) And even Enid Blyton’s fantasyland isn’t as innocent as it looks. Stay too long in the Land of Do-As-You-Please and it will rotate away from the top of the Magic Faraway Tree, with you in it. A chill wind will come up, the sun will go out like a candle, and the ladder back to everything you know and love will be whisked away forever. Et in arcadia ego.

Woolf saw fantasy as a childish thing, a form of cowardly escapism, shameful in the way that childish things are. Life had taught him to see it that way. After his father died, at the age of forty-seven, Woolf’s mother retreated into a domestic fantasy life every bit as fantastical as Enid Blyton’s. She couldn’t or wouldn’t face up to the hard realities of daily life, and the contempt she inspired in Woolf ran so deep that it became a permanent feature of his personality. “She lived in a dream world which centred on herself and her nine children,” he wrote in Sowing, the first volume of his autobiography. “It was the best of all possible worlds, a fairyland of nine perfect children worshipping a mother to whom they owed everything, loving one another, and revering the memory of their deceased father.” This struck Woolf as sheer laziness, and cowardice. It enraged him, and he never stopped calling her on it, no matter how many unpleasant scenes he caused. There would be no fays for her. Glendinning reports that all the Woolf children had a special nickname for their mother: Lady. “All the children except Leonard, that is. He alone never called her ‘Lady.’ He called her Mother.”

Woolf may have been right about Mother, for all we know, but he was wrong about fantasy. In the world of fantastic literature, emptiness and fullness are both present. Magic holds out the possibility that magical thinking will come true, that death is an illusion, and that all possible good things will in fact arrive in due course… but they never actually do. Harry Potter can summon his broomstick, but he can’t bring his parents back to life. In that respect the world of fantasy isn’t all that different from real life. Our world, Earth, is also a hybrid world, both quick and dead, fashioned from inanimate matter but haunted by a meaning that never fully manifests itself—the delusion that all will be well, because all should be well, because we want it to be well. It’s a delusion that often seems strangely real even to grown-ups. Magical thinking is something we never quite shed. It’s not infantile at all, it turns out. It’s human.

Much of fantasy literature arises from this essential truth: that magic is not the end of all your problems, it’s the beginning. Travel deeper into the realms of gold—farther up and farther in, as Aslan says—and you leave reality behind, but only to reencounter it in transfigured form.

*

Reality in Jaffna wasn’t easy. Woolf contracted malaria and eczema and dysentery, and he almost died of typhoid. Charles, his loyal wire-haired terrier, did die, from heat exhaustion. The bungalow didn’t seem quite so large once they were both living in it, but Woolf and Dutton did their mutual best to rub along and find common ground. They make an odd pair, reminiscent in their way of Jake Barnes and Robert Cohn in The Sun Also Rises: Jake cynical and world-weary, taking pride in seeing things as they are, Cohn socially inept and unable to distinguish between life and the South American adventure novel The Purple Land (by W. H. Hudson, now as forgotten as The Log of the Flying Fish): “For a man to take it at thirty-four as a guide-book to what life holds is about as safe as it would be for a man of the same age to enter Wall Street direct from a French convent, equipped with a complete set of the more practical Alger books.”

Like all great buddy-comedies, the story of Woolf and Dutton includes an attempted makeover. Woolf made Dutton take up tennis, at which he was hopeless; he mostly played with Jaffna’s two missionary ladies, the virtuous Misses Case and Beeching. Woolf and Dutton threw a bridge party for which Dutton cleaned up the bungalow and made a mighty effort to decorate it. The event was a qualified success: the missionary ladies attended, as did the government agent, the ranking civil servant in Jaffna, but otherwise it seems to have been a grim affair. Dutton played his own arrangement of Beethoven’s Fifth on the out-of-tune piano, which is something he apparently did on a nightly basis anyway, whether or not guests were present. Woolf immortalized the evening in a poem, addressed, perhaps, to one of the Misses:

You listen, even as I do, to the notes

The awful iteration of Fate’s hand,

Hammer upon the tinkling cracked piano—

I wonder if you really understand.You hear him sounding it out in the other room,

The bitterness, doom and mockery of each thing—

As you sit there silent, I wonder, do you hear

The exquisite note of degradation ring?

One hopes that Woolf, unlike Dutton, kept his poetry to himself.

All Englishmen who were in their twenties in 1905 had at least one thing in common: They’d watched the world of their childhoods die. Just as they were coming of age, electricity replaced gaslight. Cars and buses replaced horses and bicycles. Urban populations were exploding, mass media and advertising were yammering, and mechanized warfare crouched in the wings, ready and waiting. The early twentieth century looked and sounded and smelled nothing like the late nineteenth. “In those days of the eighties and nineties of the nineteenth century the rhythm of London traffic which one listened to as one fell asleep in one’s nursery was the rhythm of horses’ hooves clopclopping down London streets in broughams, hansom cabs, and four-wheelers,” Woolf would write, toward the end of his life, in the unimaginable year of 1960. “And the rhythm, the tempo got into one’s blood and one’s brain, so that in a sense I have never become entirely reconciled in London to the rhythm and tempo of the whizzing and rushing cars.” Woolf felt displaced, like the hero of H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine, exiled in the future. So did everybody else—Evelyn Waugh once remarked that if he ever got ahold of a time machine, he’d put it in reverse and go backward, into the past.

It’s no accident that both modernism and modern fantasy made their entrances at that moment, in that same displaced generation. It’s rarely remarked upon, but just as Virginia Woolf and Joyce and Hemingway were inventing the modernist novel, Hope Mirrlees and Lord Dunsany and Eric Rücker Eddison were writing the first modern fantasy novels, at least in the form most fans are familiar with. This happened for a reason. Modernism and fantasy were two very different responses to the same disaster: the arrival of the modern era and the death of Woolf’s beloved nursery-world. Though like siblings—or roommates—who are mortally embarrassed by each other, they’re not in the habit of acknowledging the connection. Like Woolf and Dutton, modernism and fantasy are each other’s uncanny double.

The resemblance isn’t immediately obvious. The modernists were interested in confronting reality directly, and meticulously documenting their experiences of it—like Woolf, they had no patience for those who dallied with fays. The modernists are the cool ones: modernism is the twentieth century’s most canonized, most critically decorated literary movement, while fantasy remains one of the least assimilated and least critically understood genres. Over the years the academics who tend the canon have extended rope ladders down to some of the “lower” forms: science fiction, detective fiction, comic books. But never fantasy. High-status literary novelists love to dabble in genre writing—David Foster Wallace, Margaret Atwood, Doris Lessing, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Cormac McCarthy have all written science-fiction novels, for example. But by and large fantasy remains proudly, stubbornly culturally radioactive. The fantasist is not a pukka Sahib.

But fantasy and modernism aren’t just opposites, they’re mirror images of each other. When the social, cultural, and technological catastrophe that inaugurated the twentieth century took place, leaving the neat, coherent Victorian universe a desecrated ruin, all that was left for writers to do was to sift disconsolately through the rubble and dream of the organic, vital world that had once been. Modernism was pieced together out of the jagged shards of that shattered world—it’s a literature made of fragments, the better to resemble the carnage it represented. Whereas fantasy was a vision of that lost, longed-for world itself, a dream of a medieval England that never was: green, whole, prelapsarian, magical.

Here and there you can spot their shared heritage, the places where modernism and fantasy touch. Modernists and fantasists both rework myths and legends: you can watch King Arthur and his knights trot, obscured but still visible, through Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (in the person of the knightly Percival), and Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (“Arser of the Rum Tipple”) to emerge into the sunlit meadows of T. H. White’s The Once and Future King. Modernism and fantasy are set against the same landscapes: verdant preindustrial hills and dark, broken ruins. La tour abolie of “The Waste Land” is the architectural double of Orthanc, the tower of Saruman the White in The Lord of the Rings. The green fields of Narnia abut the “fresh green breast of the new world” that Fitzgerald invokes at the end of The Great Gatsby.

But by the time we reach them, those green fields are always in decline. The spell never lasts. King Arthur is always dying, and the Elves are always shuffling off toward Valinor, where mortals cannot follow. Narnia falls into chaos, then drowns and freezes, and the survivors retreat into Aslan’s Land. We think of fantasy and modernism as worlds apart, but somehow they always end up in the same place. They are perfectly symmetrical. Fantasy is a prelude to the apocalypse. Modernism is the epilogue.

*

Woolf had a private fantasy that he cherished. It was about B. J. Dutton, and how, in another world, he might perhaps have found happiness:

The only possible way in which I can imagine he might have cheated fate or God or the Devil would have been for him to have obtained a safe, quiet post in the Inland Revenue or the Post Office and to have lived a life bounded on the one side by Somerset House or St. Martin’s-le-Grand, and on the other by a devoted mother and a devoted old servant in Clapham or Kew.

I have a fantasy of my own about Woolf and Dutton. It goes like this: After a couple of months living together, Woolf has a change of heart about Dutton’s poetry. He experiences an epiphany. He grasps the deeper meaning of the fays, and the nature of Dutton’s vision, however crudely expressed. He recognizes that this shy, awkward chap is at heart a fellow yearner like he is for the vanished past, the past that never was, and a mourner like he is for the world’s fall from grace. One night the awkward chitchat and murdered Beethoven give way to a moment of spiritual recognition—mon semblable,—mon frère! They return to England the best of friends, Woolf to be reunited with the scattered Apostles, Dutton to take up his place as the poetical rival of Lewis and Tolkien. Both men achieve their share of peace and contentment.

It was not to be. He may have been touchy and funny looking but Woolf was, at heart, a winner. He made a great civil servant. He was transferred and promoted, eventually rising to the rank of assistant government agent for Hambantota, a region in southeastern Ceylon that encompassed about one thousand square miles, with a salary of 650 pounds per annum. In 1912, after seven years on the magic mountain of Ceylon, he took a leave of absence and returned to the chilly realities of England, where after a passionate courtship he made an excellent match with the sophisticated bourgeoise Virginia Stephen. He resigned his position and took his ordained place among the mandarins of the Bloomsbury group. In addition to nursing his wife through numerous breakdowns, to the infinite enrichment of English literature, Woolf cofounded the Hogarth Press—publisher of “The Waste Land”—wrote several influential monographs about the international economy, and played a key behind-the-scenes role in the founding of the League of Nations. He lived to be eighty-eight. There is a tiny but still satisfying bit of nerdy irony in the fact that, after his wife’s suicide, Woolf lived out his last years in the loving company of a woman named Trekkie.

Dutton’s story doesn’t end as happily. He stayed behind in Ceylon, where he did not prosper—he “remained a failure in every direction,” as Woolf put it—although he was eventually promoted from police magistrate to district judge in Matara. He married one of the missionary ladies, Miss Beeching, whom Woolf described as having “a curious face rather like that of a good-looking male Red Indian.” (Like Dutton, Beeching is an extremely minor but still identifiable historical figure, a pioneer among women missionaries who worked in Canada before coming to Ceylon. Touchingly, in One Hundred Years in Ceylon, or, The centenary volume of the Church Missionary Society in Ceylon, 1818–1918, it is recorded that in 1906 she married one “J. B. Dutton.”)

Dutton was a social leper, but as a writer he wasn’t alone, though he probably didn’t know it. If he’d had the Internet, he would have realized that back in England the Antiquarian Revival was in full swing. The future was all before him. Hope Mirrlees isn’t much read anymore, but from the moment their work was published J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis have never gone out of print, and the turn of the millennium has seen a massive resurgence of interest in fantasy. Since 1997 J.K. Rowling has sold 150 million Harry Potter novels, and The Lord of the Rings movies earned almost $3 billion at the box office. So far in this millennium it’s the Duttons, not the Woolfs, who are in the ascendant. (Woolf surely knew, when he compared Dutton’s mind to the intestines of the beasts he killed, that the Romans used to read the future in the entrails of dead animals.)

As it happened, Matara was the next district over from Hambantota, and Woolf and the Duttons occasionally bumped into each other. In a memorable passage from Growing, they share a final dinner together under a wild tropical night sky, beside a sea out of which turtles poked their heads in the darkness. “The sky, the sea, the stars, the turtles, the bay, the palms were so lusciously magnificent at Tangalla Rest House that Nature seemed to tremble on the verge—I don’t think she ever actually fell over the verge—of vulgarity.” (Even in a state of ecstatic transport, Woolf the proto-modernist always had the question of good taste on his mind.) It was the last hurrah of the preindustrial nineteenth century, a world living on borrowed time. A few years later the automobile would arrive in Ceylon, and that was the beginning of the end of Woolf’s clopclopping nineteenth-century rhythm. The district of Hambantota would eventually be almost completely obliterated by the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004.

Dutton was living on borrowed time, too. He would never see Middle-earth or Narnia. He couldn’t catch a break for the life of him, though at least he was to be spared the horrors of World War I (unlike Lewis and Tolkien, who were both survivors of the Somme). His marriage had gone sour, and Mrs. Dutton, née Beeching, had gotten hugely fat. To Woolf’s eyes Dutton seemed to have become even tinier and more insignificant, as if she were slowly devouring him like a monstrous parasite.

A few months after their dinner together, Woolf happened to be passing through Matara, but he found Bernard Joseph not at home. Mrs. Dutton was there alone, in a house so obsessively neat and clean it reminded Woolf of an antiseptic ward at a hospital. She unburdened herself to him. “She told me that her marriage was a complete failure, that Dutton was so queer that he ought not to have married, and that she was completely miserable, and, as she spoke, the tears ran down her cheeks.” Woolf goes on to describe a surreal scene in which Mrs. Dutton insisted that he take a tour of the house, and led him to her bedroom. “Whether my nerves had given way and I was no longer seeing things as they really were, I do not know,” he wrote, “but it seemed to me that I had never seen a bedroom like it.” It was full of yards and yards of clean linen and voluminous white mosquito netting that hung over separate beds. “It gave me the feeling of unmitigated chastity. It was the linen of nuns and convents rather than of brides and marriage beds.” One wonders if, in writing this, fifty-five years later, Woolf cast his mind back over his own famously sexless marriage.

He wisely kept both beds between them, and made his escape as quickly as he could. “I never saw Mrs. Dutton again,” he wrote. “And a year or two later, when I had left Ceylon for good, I heard in England that Dutton had died of tuberculosis.”

The only other trace of Dutton’s passing I could find is in the Midsummer 1912 issue of the Cottonian, the alumni magazine of Cotton College, his old high school. The lead story is a remembrance of Hugh McElroy, another old Cottonian, who was chief purser on the Titanic, which sank in April of that year. But a little farther down in the Old Boys’ Corner there appears a notice of the death of Bernard Joseph Dutton (’93), former district judge of Matara, Ceylon. The magazine loyally praises him as a “brilliant scholar and linguist.” The previous year he had given up his post and returned to England, and he died on April 21, 1912, in Holywell, aged thirty-six years. “In his office of Judge he was loved by the natives and respected by all Europeans in Ceylon. R.I.P.”