The sky over Beijing on an October morning in 2008 was the color of a bruise, a livid yellow-brown that, my friends explained, was a sandstorm off the Gobi Desert, plus inversion, plus smoke from the coal that heats and powers the city, plus automobile exhaust. Visibility was minimal. You could make out cars going by in the street and barely make out figures walking on the opposite sidewalk. They looked like people wading through morning haze in a T’ang dynasty poem. It seemed a metaphor for contemporary China: the Gobi desert for the vastness of it, the coal smoke for the industrial revolution, phase one, and the carbon dioxide for the industrial revolution, phase two.

By the next morning a wind had come up, a light rain had passed through, and the sky was pure azure. From our slight elevation in the north of the city we looked out over crisp blue air and high clouds, the sprawl of endless neighborhoods, and, hovering over them, a forest of cranes—Beijing transforming itself. In the interim, I’d sat in an auditorium listening to a poetry reading, in Chinese and English, and seen the premiere of a new Chinese film. Both were so surprising that they made the suddenly transformed weather also seem like a metaphor.

The film, 24 City, directed by Jia Zhange Ke and written by him and a poet named Zhai Yongming, tells the story of the closing of a factory in the city of Chengdu, in Sichuan Province. The factory, a dinosaur of the planned economy, was situated in an immense, paternalistic company town where thousands of people had worked at jobs and lived their lives, performing the tasks involved in fabricating airplane engines and refrigerators. The combination of long, slow pans of empty buildings, the animated faces of the storytellers, the way their stories made a fifty-year history of their country, the sudden, meditative cuts to spaces of silence in which objects spoke, made for a sense of elegy and wonder at the shapes lives take and the way people live inside the worlds given to them—a mix which also gave the film a terrific sense of aesthetic risk and surprise.

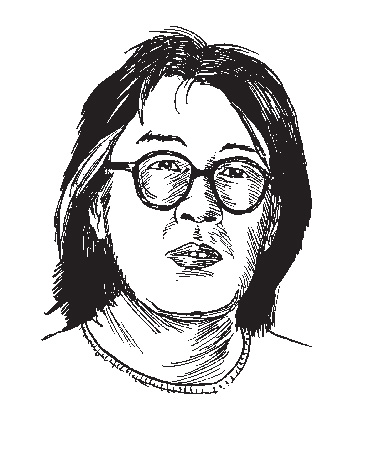

Zhai Yongming, the poet who had cowritten the film, was born in 1955 in Chengdu, so she was writing about a world that she was familiar with. I knew that she had been sent away for two years of rural reeducation during the Cultural Revolution, and that she had published her first book of poems, a work about the lives of women, in 1984. That was about the time that a new generation of poets appeared in China who had broken with the official...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in