In 1900, Josiah Flynt Willard, writer, amateur sociologist, and sometime hobo, published Notes of an Itinerant Policeman. In the book, he describes the often-unsavory world of fin de siècle American tramps: their begging strategies, their caste systems and codes, their hot tempers and underdeveloped intellects, their reasons for becoming tramps in the first place (number one: liquor). One of the book’s more compelling chapters is entitled What Tramps Read. This is one facet of tramp life one might not immediately think of, but its inclusion in the book makes a lot of sense. Because, really, who has more time to read than a tramp? As it turns out, they’re not all that different from the rest of us. When young, they like “dime novels and stories of adventure”; later, they graduate to pulps, for their “spicy articles and glaring pictures.” Detective stories are popular, as are the works of Charles Dickens, Victor Hugo, and William Thackeray, even if, as one tramp tells Willard, Vanity Fair could have been much improved had it been “choked off in the middle.”

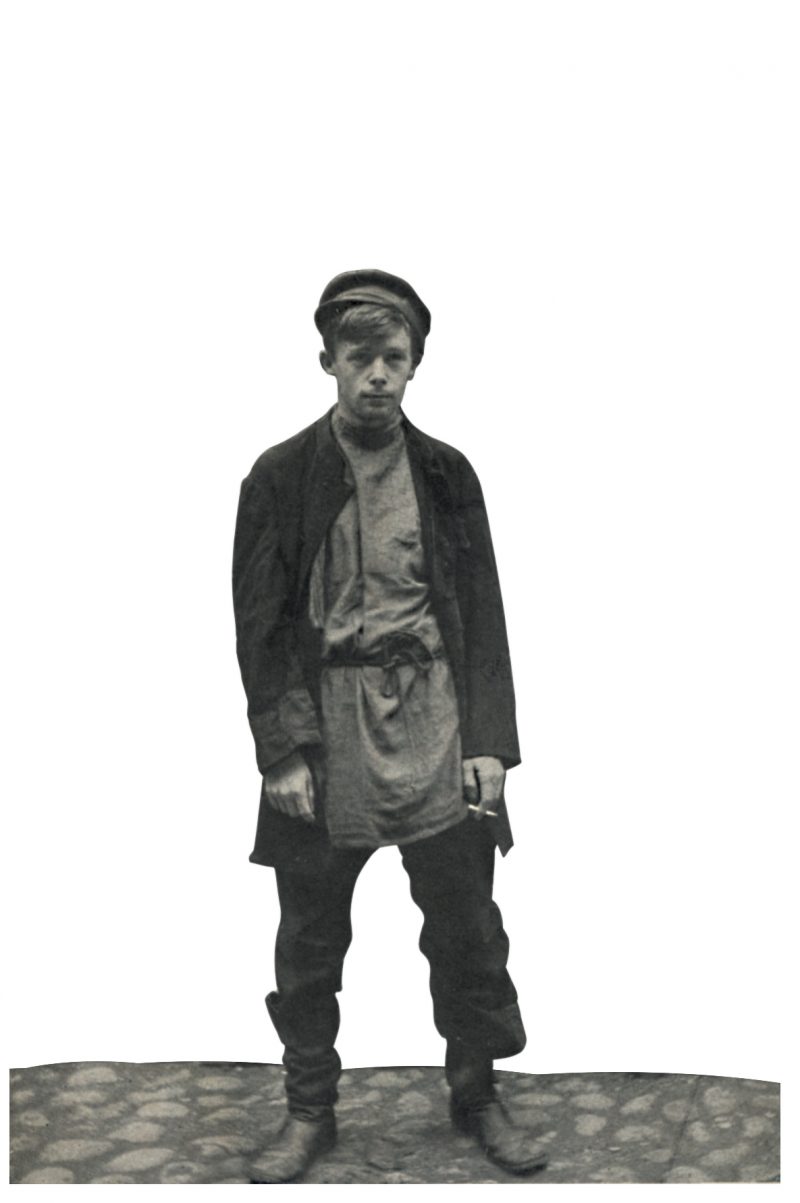

One author these wandering readers might not have cared for, however, was Willard himself. At nineteen, the Illinois native embarked on an eight-month tramp through several states, riding the rails, begging for meals and clothes, learning the hobo’s arcane language. Over the next decade, Willard entered college, left college, tramped through Germany, Italy, and Russia, met Ibsen and Tolstoy, then tramped some more. Under the pen name “Josiah Flynt,” Willard wrote stories of his adventures for magazines and journals of the day. By the time Willard published his first book, Tramping with Tramps, in 1899, he was the country’s foremost authority on the subject. Van Wyck Brooks, Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Flowering of New England, called him the Audubon of the tramp world. Jack London dedicated his own tramp diary, The Road, to Willard, describing him as “the real thing, blowed in the glass.”1

In his works, Willard neither romanticized tramp life nor defended it. If, as Todd DePastino noted in Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America, “Willard challenged the middle class’s conventional wisdom about tramps, overturning fearsome stereotypes that had been born during the crisis years of the 1870s,” it was hardly intentional. For Willard, these men and boys were lost souls: too lazy to work, too cowardly to steal, addicted to tramping in the same desperate manner that others became hooked on alcohol and tobacco. Willard was a lot like them, as one might expect, and shared many...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in