It’s a blustery Tuesday morning in mid-January, one week into the Ukrainian New Year. The plainclothes team of Oleg, Vanya, and Vova are sitting in their unheated office on Mercanskii Street. They are chain-smoking, fogging up the bare, icy room with blue clouds, using their counterfeit Marlboros to plot out the day’s appointments.

They are known out on the street as the Third Reich, and they like that name.

Out the dim window, Dneprodzerzhinsk, population 350,000, spreads itself across both banks of the Dnieper River like a big mistake nobody has owned up to yet. Known for its tough cops, the city was named after Felix Dzerzhinksky, the feared director of the Soviet secret police, what became the KGB. Life expectancy here—after seventy years of Communism and fifteen more of the nameless and confused philosophy that came after it—pirate capitalism?—is said to be 56.5 years for males.

Whatever it is, it’s falling, and falling fast.

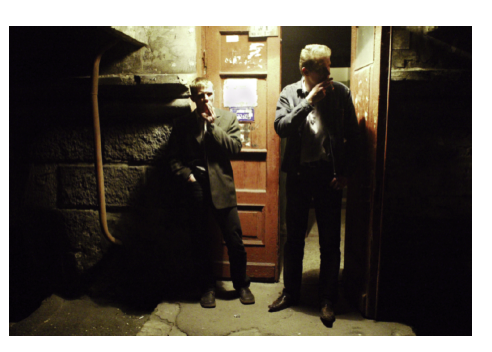

Today the team’s beat will cover the residential east side, the left bank of the river, a shabby neighborhood of 100,000. The men take their time, they know what they are doing. Their “customers” are just getting home now from a long night, some of them. One cop holds up his cigarette and examines it speculatively. The other rubs his military-style cropped scalp. The third smiles at nothing, a Buddha of the North, and silently stubs out his smoke on a cracked soap dish.

“Let’s go,” he says. It’s Oleg, the good-looking one.

The one the hard boys on the street call chort—the devil.

Should they visit the heroin dealer first? Or the B and E ring on the Mir square? At some point they will want to look in on their two teenage prostitutes, Zenia and Yulia—both sisters’ babies are sick and malnourished. They will have to take the kids away if the mommies are doing heavy drugs. This is their technical specialty: underage criminals.

The young men slowly get to their feet and put on their snappy black leather coats. Maybe they will begin with the TV-booster ring; the dope dealer will be sleeping until noon. Logistics are everything on this job; the paramount concern is to save gas. Plainclothes cops in Dneprodzerzhinsk must pay for their cars, their gas, ballpoint pens, and office paper—even their own handguns.

“All you get is a chair when you join up,” says Vanya. “A wooden chair, that’s it. The rest you must supply yourself.”

Today they are using Vanya’s car. A five-year-old blue Lada sedan, no markings. They don’t use warrants and they make no big show of brass badges, either. It’s all very informal,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in