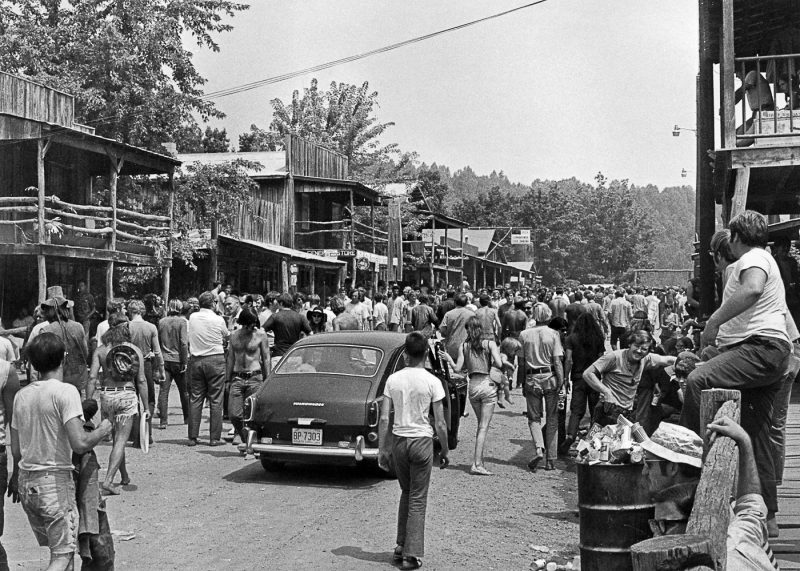

When he was eleven years old, Andy Barker knew what he wanted to do when he grew up: build a real-life Old West town in his home state of North Carolina. When he was twenty-one and writing letters from the World War II foxholes of France, he told his mother about his plans for his “Western town,” calling it one of his “best ideas yet since I’ve gotten my new partner, the Lord.” In 1954, when he was thirty, Barker found the perfect plot of land in the Brushy Mountains just outside Statesville, North Carolina. He gave up his contracting business in Charlotte and moved his wife, Ellenora, and his two kids, Tonda and Jet, to a one-room cabin without water or power.

He called his town Love Valley.

It may have been true that Barker was just overly fond of old John Wayne flicks. But he was also a religious man with an optimistic vision of the future. In 1998, Conrad Ostwalt, a professor of religious studies at Appalachian State University, in Boone, North Carolina, published a fawning exegesis called Love Valley: An American Utopia. “Andy Barker was concerned with space disappearing,” he wrote. “For twentieth-century Americans, there is no longer an unlimited western frontier… His visions were based on the

image of the pioneer, who in Barker’s mind lived in harmony with nature and neighbors and lived the heroic life of independence and freedom.”

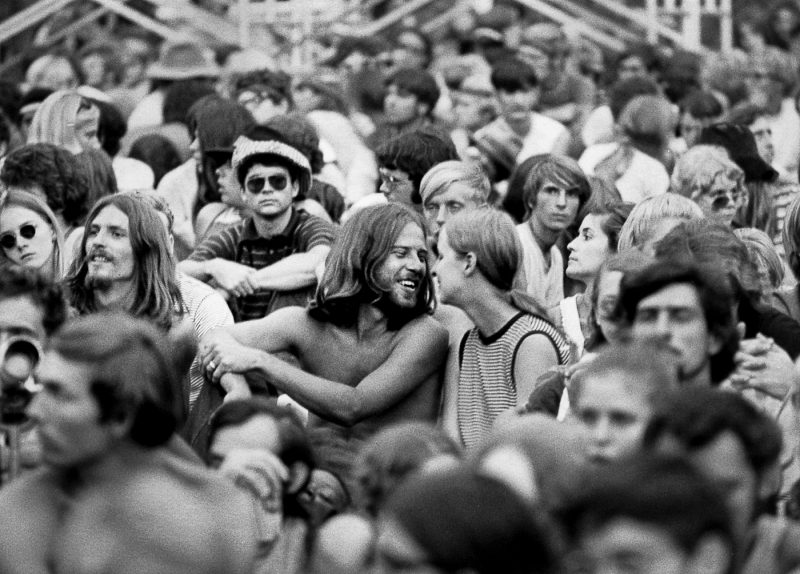

When Barker died, in 2011, at the age of eighty-seven, he was the oldest currently serving and most tenured mayor in North Carolina’s history. There was only one time, in 1991, when Barker’s name had been on the ballot and he hadn’t been elected. Primarily, however, it was Barker who ran the place—with the notable exception of the one time he willingly abdicated his office and moved out of town entirely, in 1971, following a disastrous rock festival he’d masterminded, likely in part because the town needed a new sewer system and this seemed like a good way to raise money.

The festival was called, prophetically, the Love Valley Thing.

*

In Love Valley’s early years, Andy Barker was concerned with maintaining a level of perceived authenticity. However, his main reference point was always Hollywood, never history; for a while, the town’s strictest building code stated that “all main street buildings must look a century old.”

Before building his family’s permanent home, Barker built a church. It eventually joined with the North Carolina presbytery, but remained largely ecumenical. Barker’s intentions were so simple as...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in