There are two kinds of artist: One kind infuses his or her artwork with energy and gesture and spontaneity, the other with detail and memory. The work of the first kind of artist I find consuming and satisfying, but the aftereffects fade all too quickly into general impressions. The second kind of artist seeks in the frozen moment a unique, summary image that becomes, for me, unforgettable in its specifics. As great a painter as Jackson Pollock was, I can’t recall with precision any one of his paintings; yes, I can talk about drips and reduced palette and the canvas’s size and energy, but these are features that apply to much of Pollock’s work. By contrast, I remember every Edward Hopper painting I’ve ever seen, with great clarity.

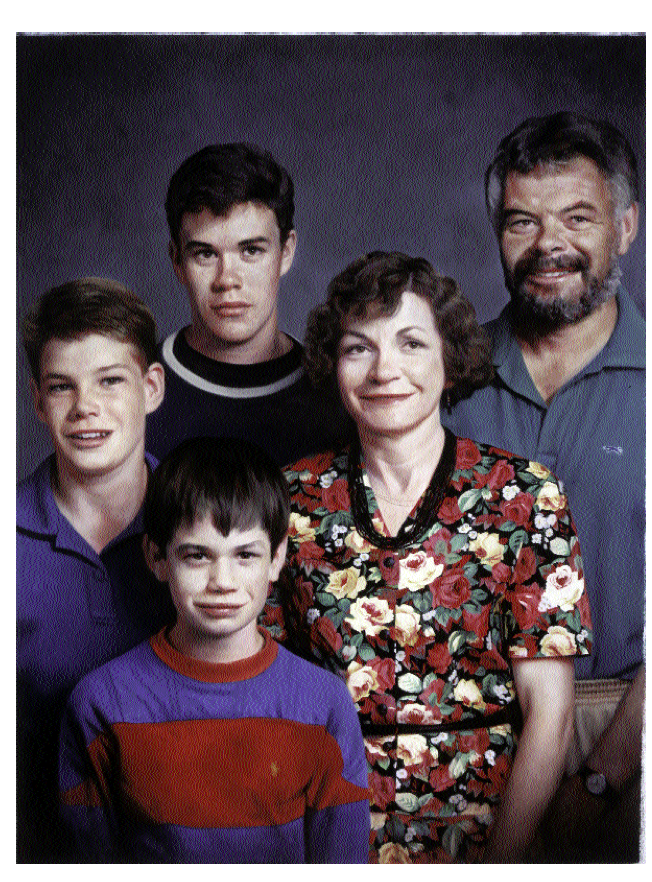

The young artists I have chosen for this issue of the Believer are mainly members of this second group of art makers. I saw their work, and I remembered it lucidly as if the images were burned on my brain. Maybe it is no coincidence that many of these artists work from photographs (with the possible exception of Claudette Schreuder). Cynthia Westwood paints predominantly from life, but she uses photos as well. David Hockney suggested in his controversial book Secret Knowledge that even the old masters used an optic device called a camera obscura to achieve their lifelike effects, and I’m with him. I have always used photos to make my work, and I don’t understand the bias people have against painters and sculptors using photos. The photograph is a great tool for the painter, and I’ll tell you why. First, the photo shows us stuff we didn’t see at the instant we pushed the button, even though we witnessed the image firsthand through the lens. When you cut a moment into a fraction of a second, nothing is still. A photo captures people off balance and unself-conscious, and for me that is when truth lies exposed.

Every artist must ask, “How much is enough?” How much description, how much paint, how much light or color, is enough to create a powerful and memorable experience? For artists dealing with representation, the photo suggests how much detail they need to make their representations “believable.” That’s what I like—believable representation. Magic occurs when an inanimate object talks back to you. We want to feel that the object is, for a moment, more alive than we are. During the Renaissance, the highest form...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in