I. THE SUM TOTAL OF THE BEAVER

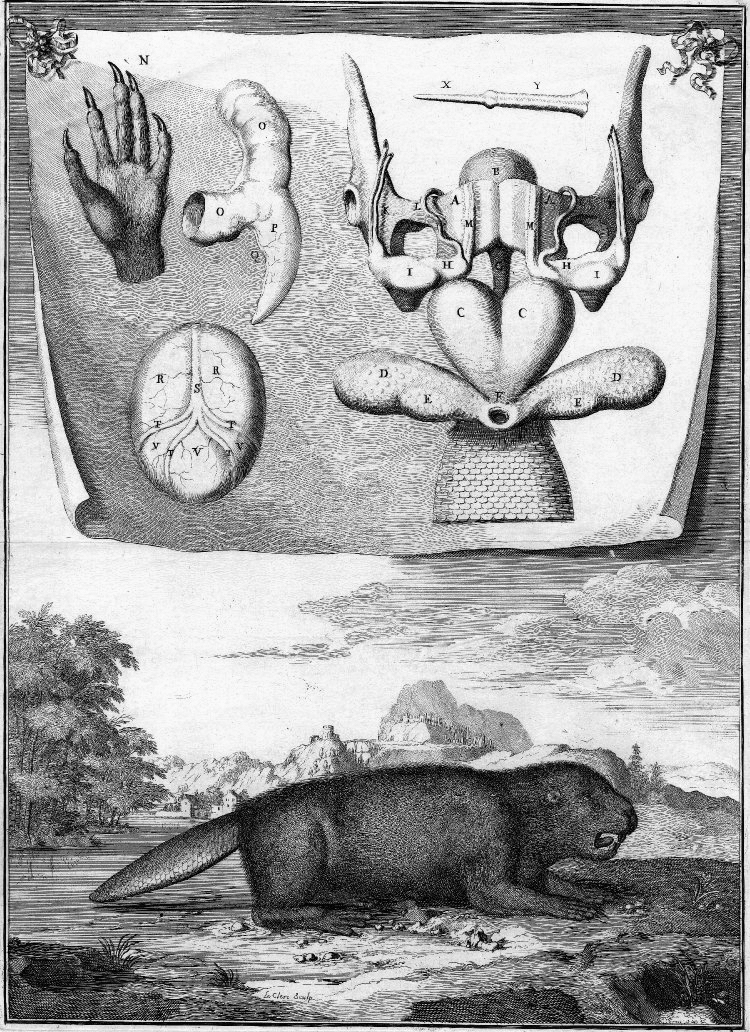

The great British collector, naturalist, and physician Sir Hans Sloane kept a young female beaver in his garden in the fashionable Bloomsbury District at the center of London. She was a paunch-bellied beast and only half grown, measuring thirty inches from the tip of her nose to the end of her tail. She lived mainly on bread, which she held with both paws, sitting on her haunches like a squirrel. Occasionally she nibbled the willow boughs that were brought for her, but she preferred the vines growing in Sloane’s garden and gnawed several of them down to the roots. She was never heard to make any noise, except a few short grunts when chased or angered. Most of all she loved to swim in a fountain filled with live flounder, which she ignored. Her excrement was jet black and extraordinarily fetid. Her urine was turbid, white, and pungent. Where the beaver hailed from, who sent her to Sloane, and when she came to the garden are lost to time, but she was decidedly dead three months after her arrival, when Cromwell Mortimer, Sloane’s neighbor and good friend, dissected her remains, in 1733. The beaver had suffered a bout of convulsive fits. She recovered and was well enough until the day she was torn apart by a dog.

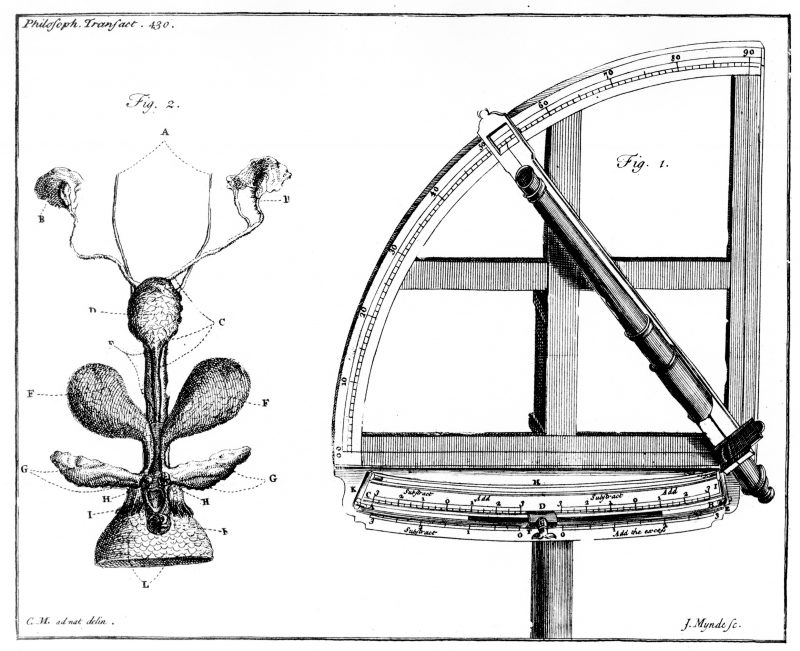

This much we know from a paper Mortimer published in Philosophical Transactions. At the time of the beaver’s death, Mortimer and Sloane were at the heart of London’s scientific community. Sloane was president of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, succeeding Isaac Newton in the position. Mortimer was the society’s secretary, and, as secretary, he was responsible for circulating any and all noteworthy observations, experimentations, and innovations in the society’s journal, none other than Philosophical Transactions.

Taken on its own, Mortimer’s sketch of a beaver ambling about an English garden hardly constituted useful knowledge for his enlightened readers. After all, this was the eighteenth century. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit invented the mercury thermometer in 1714. Edmond Halley had discovered the proper motion of the stars in 1718. And Carl Linnaeus would publish the first edition of his revolutionary ordering system, Systema Naturae,...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in