Nelson Algren was the son of a no-luck working stiff and the grandson of a religious zealot turned grifter, and he was a type of loser we can’t stomach in this country. Algren made his living as a writer for forty years, occasionally to great acclaim. At the height of his career, wealth, leisure, and the lasting respect of his peers were on offer, but Algren shrugged at those prospects and kept going his own way. For Algren, the decision was as much a question of constitution as it was of rational choice, and he paid for it dearly. America has always been able to countenance beggars, short-con men, and nine-to-fivers who just can’t get ahead, but we’ve never known what to do with the type of person who could have been really big but chose not to make the concessions required.

Algren wrote eleven books in his lifetime: one polemical, amateurish, and overwritten; five brilliant; one bitter, satirical, and unfocused; and four very good; more or less in that order. [1] From the publication of his first book, in 1935, until his death, in 1981, every word Algren wrote was guided by the belief that writing can be literature only if intended as a challenge to authority. He didn’t compromise that position when Hollywood called, or the FBI, or Joseph McCarthy, junior senator from Wisconsin, or even for the sake of his own sanity after he decided that his life’s work had been in vain. Which may be why all of his books were out of print when he died, alone in the bathroom of a $375-a-month Long Island rental, at the age of seventy-two. Only a few friends, no family, and a single black-clad fan were present at his funeral to hear Joe Pintauro, a young writer of short acquaintance, read seven lines of Algren’s poetry as a pressboard coffin was lowered into the ground:

Again that hour when taxies start deadheading home

Before the trolley-buses start to run

And snow dreams in a lace of mist drift down

When from asylum, barrack, cell and cheap hotel

All those whose lives were lived by someone else

Come once again with palms outstretched to claim

What rightly never was their own [2]

*

Algren was born Nelson Algren Abraham in Detroit in 1909, where his father, Gersom Abraham, worked at the Packard plant. Gersom was a plodding, uneducated, inarticulate man who married young, regretted leaving the family dirt farm in Indiana, and felt most at ease with mechanical objects. “Other men wished to be forever drunken,” Algren once wrote. “He wished to be forever fixing.” Gersom made a living as a mechanic, mostly, but had a regular habit of hitting his superiors without warning, for reasons he never could verbalize. At one point he opened a garage, and ran it with so little guile that his teenage son, Nelson, felt obliged to tell him that when he sold parts he should mark up their price. Gersom declined the advice, and eventually lost everything to repossession or foreclosure.

The family moved to Chicago in 1913, and settled in a South Side Protestant neighborhood, where Algren had a sandlot sort of childhood. He delivered the Abendpost with a pushcart, and picked up discarded corks and bottles for pocket change. When the White Sox were in the World Series, Algren began calling himself “Swede,” after Swede Risberg—the Swede walked pigeon-toed and so did Algren. In 1921, the family moved to the Near Northwest Side and Algren, then twelve, began sneaking into the local pool hall. When gamblers connected to Capone opened the Hunting House Dancing Academy on the same block as his father’s garage, Algren talked his way past the doorman and went upstairs, where he learned to gamble and watched police officers collect bribes. By seventeen he had ditched his childhood friends and begun exploring Prohibition-era Chicago, knocking on the unmarked doors of speakeasies and offering the phrase “Joe sent me.” [3]

In September 1927, Algren began attending the University of Illinois, Urbana. His parents couldn’t pay, or understand why he wanted more schooling, but his older sister Bernice could. She had married into a small amount of money, and offered to help finance his four years at Urbana. To cover living expenses, Algren worked for the university, hustled pool, and set pins in a bowling alley. Later he claimed that he spent his free time in Chicago’s slums and never socialized on campus. In his sophomore year Algren decided to become a sociologist, and then resigned himself to journalism because he couldn’t afford a master’s degree. He graduated the next year, possessed by the very American dream of making a living writing respectable, sociologically informed journalism.

Never mind the bleak 1931 economy, Algren believed he was going to have an easy time finding work. He borrowed money for an interview suit, passed a test administered by the Illinois Press Association that qualified him as a reporter or editor, and set off hitchhiking through the Midwest clutching a card certifying he was a newspaper man. He stopped in Minneapolis, where he lived in a whorehouse and then the YMCA, and wrote headlines for the Minneapolis Journal. He was there for a few weeks before asking for his check and learning there wouldn’t be one. The paper had been doing him a favor, he was told, by allowing him to gain experience. Defeated and broke, he hitched back to Chicago and the home his parents had just mortgaged. He was depressed and directionless, and when his family pressed him to find work, he headed south.

Among the tens of thousands of hobos hitching and hopping freight that summer in search of work they never did find, at least one wore a suit bought with borrowed money. Algren still thought he could find work with a newspaper, and applied to every one he found as he drifted through Illinois, down the Mississippi, and through east Texas. His tramping ended in New Orleans, where he slept under the stars, on park benches or in alleys, and lived off chicory coffee and bananas given to him by a local mission.

By the end of the summer, Algren submitted. He pawned the suitcase but kept the suit, which may have been the thing that attracted the Luthers. The Luthers were a pair of confidence men who shared a pseudonym and needed a legit-looking patsy. One was a Texan with a steel plate in his skull, a remnant of a World War I injury; the other was a Floridian, long on get-rich-quick schemes and short on work ethic. Algren met them while working door-to-door sales on commission and rarely earning enough to eat. He was young, pretty, and poor enough to demean himself: exactly what the Luthers were looking for.

The new trio printed counterfeit certificates for free hairstyling that they distributed, for a small gratuity, to every New Orleans housewife who answered when they heard a knock. The scam earned one of the Luthers a beating from a group of angry husbands. After that, the group fled the city for the Rio Grande Valley, where they picked fruit for seventy-five cents a shift, until the day the steel-skulled Luther returned to the picking shed holding a pistol and informed the other two that they were going to rob a supermarket called the Jitney Jungle. Algren and the Florida Luther ran again, and stopped next in Harlingen, Texas, where Luther convinced a Sinclair agent to lease them an abandoned gas station on a road no one drove. Algren signed the papers, took responsibility for the station, and bought gas with money provided by a friend from Chicago. As a sideline, he shucked and canned black-eyed peas, received on credit from local farmers. Luther disappeared and then returned only long enough to siphon gas and vanish again, leaving Algren to answer to the farmers and account for their debts to Sinclair; he nearly starved.

“Well, here you get to be a writer when there’s absolutely nothing else you can do,” Algren told the Paris Review in 1955. Harlingen was the place where he realized there was nothing else he could do. Hungry, alone, and having just been hustled, he limped home. He was picked up for vagrancy in El Paso, and walked out of the drunk tank through the cell’s unlocked door.

When Algren returned to Chicago, by way of a thousand small towns, he possessed nothing but a few angry letters written on the road and a new dedication to writing. His vagabondage had divorced him of his middle-class pretensions. He had tried to play by the rules and hadn’t made good, and maybe, he reasoned, the same was true of the people he had met in Chicago’s slums, New Orleans’s whorehouses, and Texas’s hobo jungles. He had witnessed enough predation during his year on the road to last a lifetime. All of it troubled him, but none more than the violence committed under the guise of authority: the police who beat train jumpers for reward money, or locked Algren up for being broke in the wrong town. From that point forward, no matter his sporadic moments of fame, Algren identified himself with society’s losers. Even near the height of his influence, in 1953, he described a writer’s proper stance toward the status quo by writing: “If you feel you belong to things as they are, you won’t hold up anyone in the alley no matter how hungry you may get. And you won’t write anything that anyone will read a second time either.”

In Chicago, Algren lived with his parents and associated himself with a group of young writers. He produced a consistent string of rejects before Larry Lipton, a friend and fellow author, suggested that he rework one of his Texas letters into a piece of short fiction. The result, “So Help Me,” is a retelling of Luther’s plan to rob the Jitney Jungle that results in the death of Algren’s fictional counterpart. The piece was accepted by Story magazine around the time Algren joined the Chicago chapter of the John Reed Club, which was part of a national network connected to the Communist Party. Richard Wright was also a member. He and Algren became close; six years later, Algren would give Wright the title for his most famous book, Native Son.

Algren received a letter from Vanguard Press in late 1933, asking whether he was working on a novel. Not knowing how to respond and too excited to play it cool, he hitchhiked to New York City and presented himself to James Henle, Vanguard’s president. At twenty four, Algren assessed himself as a promising new commodity and demanded what he imagined to be a professional rate. A hundred dollars, he figured, would be enough to get him back to Texas and pay for room, board, rolling tobacco, and liquor for four months, at the end of which he would have a book. Henle gladly gave him what he asked for.

Algren headed south from New York City, traveling rough, and paying close attention to the men he hoboed with. By the time his freight passed the spires of a college building in a small southwestern Texas town called Alpine, he had the main character of his first novel. The book was written, for the most part, on the campus of Sul Ross State Teachers College, which Algren accessed by presenting his commission letter from Vanguard Press to the college’s president. He wrote frantically for four months, occasionally holding court for students, and then, because part of the story took place in Chicago, he headed home. Along the way he spent a few weeks in jail, and nearly died after being trapped inside a refrigerated train car. [4]

The book produced as a result of Algren’s hoboing, incarceration, and return to Chicago’s left-wing literary circles was a polemical mediocrity. Two of the four sections of Somebody in Boots were introduced by quotations from the Communist Manifesto. The main character, Cass McKay, a petty criminal who desires only a tattoo and the love of a woman named Norah, experiences or witnesses violence and exploitation so severe they supplant the plot. In the introduction to a paperback reissue of Somebody, published thirty years after the original, Algren himself assessed the book as “an uneven novel written by an uneven man in the most uneven of American times.”

Somebody in Boots was Algren’s big chance, but when he stepped into the ring he swung and he missed. It was released in March 1935, and a year later it had sold only 762 copies. Algren hadn’t found a straight job, and after his publishing failure it seemed he wouldn’t be able to make it as a writer. He had nowhere to go, and no idea what to do next, and so resigned himself to nothingness. In the apartment of a girlfriend whose name has been forgotten, Algren removed the gas line from the back of a stove, placed it in his mouth, and breathed methane. The girlfriend discovered Algren nearly but not quite dead, and handed him over to Larry Lipton and Richard Wright, who looked after him for months. Eventually they had him committed to a hospital, which discharged him to his parents’ apartment. He spent the remainder of his life denying his suicide attempt.

Seven years passed between the publication of Algren’s first book and his second, and during those years he grew into himself and became the stubborn, hilarious, fiercely loyal, brilliant, pugnacious, and fickle person he would be until his death. He met a woman named Amanda Kontowicz at a party thrown by Richard Wright, and they began living together in desperate poverty. [5] Algren stole food so they could eat, and he and Amanda sometimes lived for days on milk, potatoes, and onions.

When she could find work, Amanda cleaned houses. Algren stacked boxes in a warehouse and then worked in a health club, where he hosed off businessmen as they completed their workouts. During those years he cultivated friendships with literary types, and also nickel-ante gamblers, criminals, and his peers, the undistinguished poor. Eventually Wright secured a job for Algren with the Works Progress Administration, first as a writer and then as an editor. After hours he went bowling with Studs Terkel and Howard Rushmore, and drank and caroused with a gang of small-time criminals who called themselves the Fallonites.

Writing came in fits and starts. Algren founded and edited the New Anvil, a journal of “proletariat” literature, with his friend Jack Conroy, and published poetry, once in Esquire. He placed a few short stories. For material, he corresponded with inmates in Illinois prisons, haunted lineups at Chicago police stations, and observed criminal trials. In 1939 he created a pretext for leaving Amanda so he would have more time to write, and by ’40 he was living in a flat without a telephone, near the heart of Chicago’s Polish triangle. Emboldened by Wright’s success with Native Son, he had begun a new book. When he wasn’t writing, he played cards in backroom games, spoke with the residents of the transient hotels lining South State Street, and visited the psychiatric institution at Lincoln.

That year marked the beginning of a stretch during which Algren would produce his greatest works. He wrote five books in quick succession: Never Come Morning, The Neon Wilderness, The Man with the Golden Arm, Chicago: City on the Make, and Nonconformity. With each one he advanced and expanded upon his conviction that the role of the artist is to challenge authority. He pressed that refrain throughout his life, at every opportunity he found. The formulation that best captures his intention and method is: “The hard necessity of bringing the judge on the bench down into the dock has been the peculiar responsibility of the writer in all ages of man.” After his first book, Algren never traded in the idea that the poor are purely victims. Sometimes the accused were guilty, he believed, sometimes innocent, either way their perspective deserved consideration.

His publisher didn’t like it, but Algren took his time writing Never Come Morning, the book that redeemed him. He delayed for artistic reasons and because both his sister and his father died before his deadline. By 1941 he had completed his manuscript; it was published the next year.

Morning contains a complete world bounded by the limits of Chicago’s Polish triangle and populated by characters who resist simple categorization. The book’s protagonists, Bruno “Lefty” Bicek and his love interest, Steffi Rostenkowski, are young, poor, self-serving, and ignorant of the world beyond the few blocks they grew up on. But neither is a caricature. Steffi, Algren wrote, is “one of those women of the very poor who feign helplessness to camouflage indolence. She had been called upon, as a child, following her father’s death, for so many duties, the family’s circumstances being so precarious, that she had early learned evasion.” Bruno Bicek is a sandlot baseball player and sometimes-boxer who lives with his widowed mother and desires fame in the uncomplicated way a child longs for birthday presents. Bicek is a tough guy, to be feared—that’s the word he puts around—but his self-image is never certain:

Bruno Bicek from Potomac Street had his own cunning, he’d argue all day, with anyone, about anything, in daylight, and always end up feeling he’d won, that he’d been right all along. He’d refute himself, in daylight, for the mere sake of an argument.

But at night, alone, he refuted no one, denied nothing. He saw himself close up and clearly then, too clear for any argument. As clear, as close up, as the wolf’s head in the empty window.

That was the trouble with daylight.

Rough as he claims to be, Lefty is a coward when it counts. One night, Bicek’s gang follows him and Steffi to a shed where they plan to have sex. The gang waits outside while Bruno and Steffi drink and make love, and when the deed is done they connive to rape Steffi. At first Bicek protests, then he pleads, then he tries to negotiate, offering the gang’s leader, Kodadek, a better position on their baseball team the following year. “Next summer we’ll both be dead,” Kodadek says, dismissing him. Rather than lowering himself in his friends’ estimation by admitting that he loves Steffi, Bicek abandons her. He leaves the scene and returns drunk. Among Steffi’s attackers he spots a stranger, a Greek, and beats him to death because he doesn’t know what else to do, because he was too cowardly to defend Steffi or fight the man fair.

By turns brutal, terrified, disenfranchised, and murderous, Bicek is a far more nuanced and challenging protagonist than any Algren had created before; and he is evidence that Algren had, in the seven years separating his first two books, decided that bearing honest witness was a more effective means of challenging authority than protest was. The world of Somebody in Boots had been a high-contrast, good-and-evil place, populated by two-dimensional characters who existed to advance Algren’s thesis. But the world of Never Come Morning is a finely rendered, gray-hued, fatalistic place populated by angry, hungry young people whose lives are governed by rules that are clear, though impossible to abide by. Not one of them is innocent. They prey foremost upon each other, but also upon the wider world, and they acknowledge responsibility for their actions and pay for them. The reader might empathize with or fear them, but they are above pity, victimhood, or stereotype.

With this book Algren got his due. The New York Times called Never Come Morning a “brilliant book and an unusual book,” and Malcolm Cowley declared Algren “not by instinct a novelist. He is a poet of the Chicago slums, and he might be [Carl] Sandburg’s successor.”

Morning went into a second and then a third printing. Algren had made a name for himself, but though he was finally confident in his ability to make a living as a writer, he couldn’t bank on his potential yet; he was broke again almost immediately. By that summer he was in East St. Louis, hanging around with the Fallonites and working as a welder, a trade he was not skilled in. He returned to Chicago after a few months and took a position with the Venereal Disease Control Project, working alongside Jack Conroy. Together they scoured the city’s brothels and transient hotels, looking for people who had contracted syphilis. Algren, of course, took notes. He supplemented his income by writing reviews for Poetry and the Chicago Sun-Times.

Algren and Amanda became a couple again, and then he was drafted into World War II. His induction form was stamped SPECIAL ASSIGNMENT, most likely because the FBI had been investigating him, at J. Edgar Hoover’s personal request, for the past two years. Algren was under suspicion of being a leftist agitator, and was never trusted to be anything more important than a litter-bearer as his unit traveled to Fort Bragg, then liberated France, the Netherlands, and Krefeld, Germany. He returned to Chicago in late 1945, rented a two-room flat on Wabansia at Bosworth for ten dollars a month, and began writing. Doubleday approached him, and off the lingering prestige of Never Come Morning Algren was promised sixty dollars a week to write a collection of stories and a war novel.

The Neon Wilderness, the resultant collection of short fiction, was published in 1947 to good sales and better reviews; its prestige would only grow with time. Six years after its publication, Maxwell Geismar judged the collection “perhaps one of the best we had in the 1940s.” In the introduction to the ’86 edition, Tom Carson declared it the book that established Algren as “one of the few literary originals of his time.”

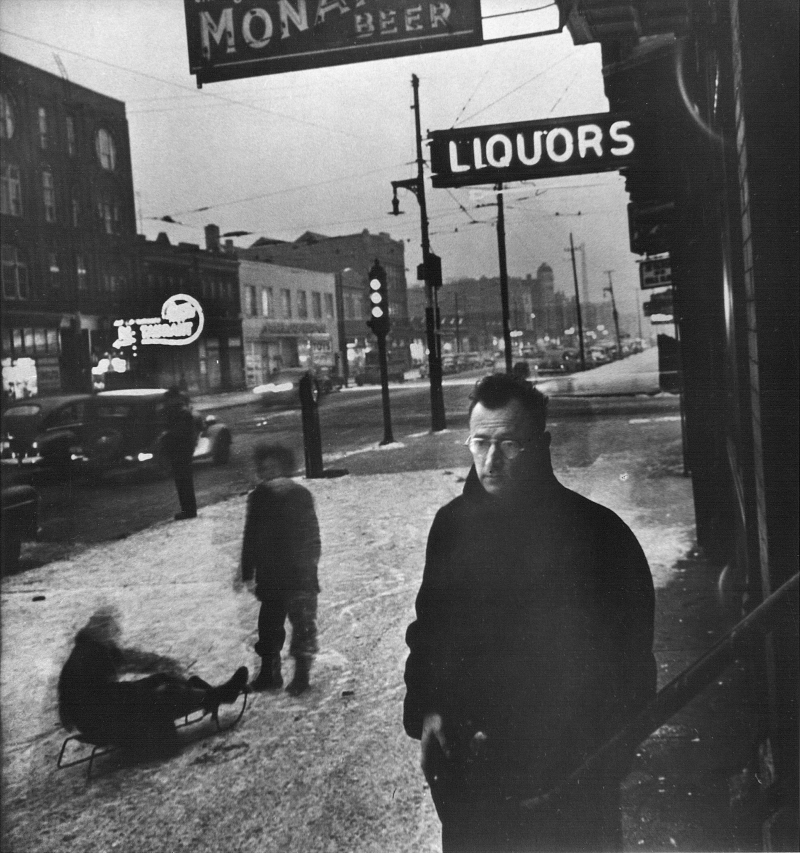

His second success turned Algren into a public figure. Jack Conroy interviewed him on TV, then a new medium, and local cognoscenti groups like the Friends of Literature began calling. His profile was such that when Simone de Beauvoir passed through town that year, friends provided his number and told her to call. [6] He was, for the first time, in demand, well paid, and confident enough to begin shaping a few hundred pages of notes into his greatest work, The Man with the Golden Arm. Through 1947 and ’48 Algren worked out of his Wabansia flat and split his social time the way he always had. He spent nights with a group of morphine addicts, going to jazz clubs. His days, when he wasn’t writing, were spent with the intellectual set, sometimes onstage giving speeches that railed against the Taft-Hartley Act, Joseph McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee, and the Hollywood blacklist.

Golden Arm, which was published in September 1949, opens slowly, revealing itself a sliver at a time in the personae of its characters: Frankie Machine, a veteran with the “right kind” of army discharge “and the Purple Heart,” who returned from the war with a piece of shrapnel in his liver and a morphine addiction. In his puddle-size world, he’s a big fish, though his only bankable skill is his ability to deal cards, which he does in a backroom game run by Zero Schwiefka. “That’s me—the kid with the golden arm,” Frankie brags. Sparrow Saltskin, “a kid from nowhere,” steers suckers into Frankie’s card game, and fills the daytime hours shoplifting and stealing dogs. Record Head Bednar, the police captain, a man “filled with the guilt of others,” picks up either of them anytime the neighborhood’s equilibrium requires it. Sophie, Frankie’s wife, who everyone calls “Zosh,” sequesters herself in the couple’s room, trapped by a psychosomatic injury and the idea that infirmity will keep Frankie from leaving her. Violet, Zosh’s only friend, cuckolds her husband with Sparrow, and justifies his thieving ways by declaring, “Lies are just a poor man’s pennies.”

If Golden Arm had a purpose, it was to challenge the idea, then congealing into ideology, that an individual’s social value is related to his or her wealth. Its message is that lives lived in the twilight hours, after swing shifts, in the shadows of newly erected towers, or beneath the tracks of the El, are as passionate, as meaningful, as funny and pointless, and as much a part of the American story as any. In Golden Arm, the war has ended and transformed the country. Postwar affluence has brought the world to Division Street in the form of billboards and handbills, television and neon signs, and an ethos that wrote the also-rans out of the script. Algren’s characters feel themselves diminished by everything new. Even the presence of a Division Street bar that serves mixed drinks is a dark portent.

In earlier books, Algren’s criminals were proud, angry, dangerous young people. Now they are older, and know they are a threat to no one but themselves. They don’t have words to name the ways their world has changed, and in place of rage they have self-pity. “‘I never get nowheres but I pay my own fare all the way,’” Frankie Machine boasts pathetically. The characters that populate Golden Arm live in closet-size rooms tucked inside weekly rate hotels; most work, drink in a dark bar called the Tug & Maul, and then retreat to Frankie’s card game, where they glance at each other, speak vaguely, and hide from the thing haunting them:

The great, secret and special American guilt of owning nothing, nothing at all, in the one land where ownership and virtue are one. Guilt that lay crouched behind every billboard which gave each man his commandments; for each man here had failed the billboards all down the line. No Ford in this one’s future nor any place all his own. Had failed before the radio commercials, by the streetcar plugs and by the standards of every self-respecting magazine.

For my money, no book more elegantly describes the world of men and women whom the boom years were designed to pass by. In the decades after Golden Arm, the country obsessed over the behaviors and fates of women and men like Algren’s characters—and dedicated millions to altering them through wars on poverty and drugs—but in 1949 Algren was nearly alone in reminding the country that having an upper class requires having a lower class. For the skill and elegance of its prose, its compassion, and its prescience, I’d rank Golden Arm among the very best books written in the twentieth century. Before Algren’s fall from favor and the onset of his obscurity, many people agreed with that assessment. The book received glowing reviews from Time, the New York Times Book Review, the Chicago Sun-Times and Tribune, even the New Yorker. Doubleday nominated it for the Pulitzer, and Hemingway, who had declared Algren the second-best American writer (after Faulkner) when Never Come Morning was published, wrote a promotional quote that went too far for Doubleday’s taste but pleased Algren so much he taped it to his fridge:

Into a world of letters where we have the fading Faulkner and that overgrown Lil Abner Thomas Wolfe casts a shorter shadow every day, Algren comes like a corvette or even a big destroyer… Mr. Algren can hit with both hands and move around and he will kill you if you are not awfully careful… Mr. Algren, boy, are you good.

A. J. Liebling, a writer for the New Yorker, followed Algren around Chicago for a story, and Art Shay, a young photographer, spent months taking pictures for a Life magazine cover story. Irving Lazar, a Hollywood agent, called to offer Algren work writing dialogue for ten times what he made writing books. John Garfield, then a leading Hollywood man, wanted to play Frankie Machine on the big screen, and he had a producer lined up. In March 1950, Algren won the first National Book Award. It was presented to him in New York City, by Eleanor Roosevelt, in a ceremony that required Algren to don a tuxedo for the first time in his life. Writing in the introduction to a fiftieth-anniversary edition of Golden Arm, Dan Simon, publisher of Seven Stories Press, describes a picture of Algren from that night. “He is biting down on a cigar and grinning to himself like a hard-boiled Mona Lisa, unmistakably a man who has taken on the world and won, and even more surprisingly, a man who had expected to win all along.”

And that was the acme: not of Algren’s talent, but of his career. The fall came fast and the landing was hard. That fact may lead you to associate this story with the now-common artistic sin-and-redemption cliché, the type that requires its talented star to succeed only so his moral failings—maybe women, maybe drugs, usually both—can unravel his career and chasten him, so that once his talent returns him to prominence he will be grayer, wiser, and much more humble. But that’s not how this story goes. Algren had his vices—he never did see a dollar that wouldn’t look better at the center of a poker table—but it was virtue that unwound his life.

Before Golden Arm was published, Algren had a profile, but not much of one outside Chicago. In the years after, anyone interested would have been able to dredge up dozens of facts that unequivocally disqualified him from being a leading cultural figure in 1950s America. In ’48 alone, he stumped for Henry A. Wallace, the Progressive Party nominee for president, helped run the Chicago Committee for the Hollywood Ten, and signed an open letter to Soviet artists decrying “the exploiters who hope to convert America into a Fourth Reich.” When he got to Hollywood in 1950, he kept company with men like Albert Maltz, who would soon be sentenced to jail for his role in the Hollywood Ten affair. More damningly, Algren had been a communist for years. [7] Worse still, he didn’t regret anything he had done and didn’t intend to change his persona or his politics.

Over the next few years, Algren paid for his intransigence in ways large and small. The FBI trailed him in Hollywood. Art Shay laid out the Life cover story and waited by the presses for the finished product; the story never ran. Algren sold the film rights to Golden Arm, and shortly afterward his Hollywood agent went underground to avoid jail. John Garfield, also under investigation for his leftist sympathies, died of a heart attack at thirty-nine. Before his death, he sold the rights to Golden Arm to Otto Preminger, who used the book to get Frank Sinatra his only Academy Award nomination for a lead role. The deal was more than a little questionable, and Algren’s biographer estimates Algren was cheated out of about $42,000 (about $360,000 today), which was far more than he had ever earned writing a book. Algren later claimed that he spent half the amount Garfield paid him for film rights and a complete script suing Preminger for control of his story. Algren had bought a small house with his proceeds, and by the end of the Hollywood debacle he had lost it to legal fees.

But it was his diminished ability to publish that cut closest to the bone. In the three years after Golden Arm, Algren wrote two short books, both nonfiction, both brilliant, unique, and unflinching in their critique of the country’s changing ethos. The first, Chicago: City on the Make, is a book-length prose poem that relays Chicago’s history through the lens of criminality. It may be among the most beautiful and brutally honest love letters ever written. The book opens with the theft of land from the Pottawatomie Indians, and ends in 1951, when “we do as we’re told, praise poison, bless the F.B.I., yearn wistfully for just one small chance to prove ourselves more abject than anyone yet for expenses to Washington and return.” Surprisingly, City on the Make received critical praise—“The finest thing on the city since [Carl] Sandburg’s Chicago Poems,” the Chicago Sun-Times decided—but unsurprisingly, it didn’t go beyond a second printing of five thousand copies.

The idea for Algren’s next book came in the summer of 1952, over drinks with a Chicago Daily News editor who asked Algren to write an essay for the paper’s book section. That winter Algren delivered a two-thousand-word anti-McCarthy essay that ran under the headline GREAT WRITING BOGGED DOWN IN FEAR, SAYS NOVELIST ALGREN. The essay ran fifteen months before Edward Murrow made his famous pass at McCarthy, and Algren’s was almost the only discordant voice. To his surprise, and his editor’s, the essay struck a chord. The Nation reprinted it, and progressive clergy members in two states introduced it into their sermons.

The essay had been extracted from a short book Algren had been writing on and off for more than a year, and in response to the attention it received, Doubleday asserted its contractual right to publish it. That was January 1953. In March, Algren was denied a passport. In April, two informants told the FBI he had been a communist in the ’30s; another came forward in June. Algren delivered his manuscript to Doubleday the same month. The book was to be published with an introduction by Max Geismar, who had assisted with the editing. Privately, Geismar wrote to Algren, “This will be one of the first books they will burn: congratulations.” In September, after delaying and then giving Algren the silent treatment, Doubleday refused to publish the book. Algren sent the completed manuscript to his agent for placement elsewhere, and it disappeared. Either his agent lost it, it was lost in the mail, or it was taken en route by the FBI—its fate has never been clear.

In 1956, Algren gave the carbons from the manuscript to Van Allen Bradley, the Daily News editor who had commissioned the essay that spawned the book, over somber drinks at Ricardo’s. After Algren’s death, Bradley delivered the carbons to Algren’s archive, where Bettina Drew, Algren’s biographer, found them. Algren’s lost manuscript was finally published, in 1996, by Seven Stories Press, as Nonconformity: Writing on Writing. In it, Algren argues that anyone can write, but literature can be created only by people who do not see themselves as part of “things as they are.” It had always been possible for the casual reader to think of Algren as a stylist whose characters were a matter of convenience or an attempt to entice a voyeuristic public. In Nonconformity, Algren set the record straight.

The book is grounded in its historic moment—“Between the pretense and the piety. Between the H Bomb and the A”—but timeless in its vision. For Algren, writing is not a trade or a hobby. It is a calling that requires practitioners give more of themselves emotionally than they can afford, and demands they tell the truest stories they possibly can, the kind that make the teller partner to the actions of their subjects, and create complicity in the telling. Everything else is just words on a page. In exchange for these sacrifices he guarantees no reward. Instead he promises commercial failure and the risk of emotional collapse, yet keeps faith with his vision and claims the other side asks more. They demand conformity.

Algren believed in the equality of ideas—not that all ideas are equal, but that the value of an idea bears no relation to the social status of the person who formulated it. That belief shapes the narrative of Nonconformity. Algren develops and challenges his argument using his own voice and the voices of dozens of others—Dostoyevsky, Fitzgerald, Carpentier, Dooley, de Beauvoir, and Durocher among them [8]—before arriving finally at the conclusion that the only vantage from which to write about America is the vantage of the impoverished. “Our myths are so many, our vision so dim, our self-deception so deep and our smugness so gross that scarcely any way now remains of reporting the American Century except from behind the billboards,” he wrote. That was a unique vision in 1953, and it still is; its suppression weakened our literary tradition.

Because he needed the money, Algren accepted a contract from Doubleday to rewrite Somebody in Boots. After stalling for three years, he went to work, not rewriting it but writing a new book that shared just enough scenes with Somebody to meet his contractual obligations. It was the first time he had written purely for the need of a check, and he judged himself harshly for the compromise. While working on his manuscript, he wrote to Millen Brand, a writer and friend, and declared that all the writers of the ’30s “gave up, quit cold, snitched, begged off, sold out, copped out, denied all, and ran.” He included himself in the category: “[Kenneth Fearing] is hacking, Ben Appel is hacking, I’m hacking too. Nobody stayed.”

Hacking or not, Algren abided by his own rules. The book was expertly written and comical, but, as in Somebody in Boots, the main character was a drifter who didn’t pretend at the American Dream. Doubleday returned the manuscript for rewrites, fearing that its publication would result in obscenity charges. Algren rewrote it, and Doubleday refused to publish it. The book went to Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, which published it as A Walk on the Wild Side in May 1956. This time the critics savaged Algren, not for the quality of the writing but for the book’s content. The vision that had made him a sensation in 1950 made him a pariah in 1956. “What he wants to say is that we live in a society whose bums and tramps are better men than the preachers and the politicians and the otherwise respectables,” Norman Podhoretz wrote in the New Yorker. Exactly right; but Podhoretz didn’t mean it as a compliment. In the Reporter, Leslie Fiedler declared Algren “a museum piece—the last of the proletarian writers.”

By September of 1956, Algren was so depressed by his reviews and his publishing prospects that his friends Neal Rowland and Dave Peltz had him institutionalized. He checked himself out two days later, and that December he walked across a partially frozen lagoon near the house he was about to lose in Gary, Indiana. He fell through the ice and was rescued by a group of working men who threw him a rope and dragged him to shore. He denied it had been a suicide attempt, but few of his friends were convinced.

*

History might have been kinder to Algren if he had died in 1956. Dead, he would have been a good candidate for rediscovery in the late 1960s or early ’70s, after the political pendulum had swung back the other way. He could have been framed as a heroic figure whose career—and life—had been cut short by McCarthy and the stifling conformity of 1950s America. You can almost see the modern-classics reissues being printed, and hear the PhD theses being typed. But he didn’t die, never quite went away, and refused to be championed.

About a year after he fell through the ice, Algren moved to a third-floor walkup at 1958 West Evergreen, near where he had lived when he wrote Never Come Morning, and a stone’s throw from where he’d grown up. He stayed in the apartment eighteen years, and for those years he ground out a steady-ish income giving speeches; selling reprint, foreign translation, and movie rights; and writing book reviews, magazine features, and three books.

From time to time the rehabilitation of his career seemed to be on offer, but he was never willing to cede the ground necessary to make that a possibility and he was too vulnerable to admit he was interested. In 1965, the Iowa Writers’ Workshop offered him fourteen thousand dollars to teach, a significant increase over its previous offers. He accepted because he needed the money, but taught on his own terms. He critiqued papers at the bar, or over a card table, and told his students that living life was the only way to become a writer. The next year he received and accepted a spate of lecturing offers, something he referred to as “Going on the Ho Chi Minh Trail,” because creating literature in ’66, as he saw it, required speaking out against the Vietnam War. Onstage Algren played a recording of Hemingway reading “Saturday Night at the Whorehouse in Billings, Montana,” and then inveighed against the war. The Tet Offensive was still two years away; the first large national protests wouldn’t happen for three.

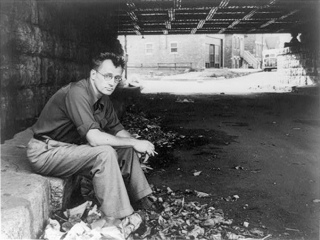

In his thirties Algren had been beautiful. He had looked like a boy from the poor side of the working class, all grown up and pretending to be an intellectual who was pretending to be a tough guy. He was trim, and had the gently angular features of a European mutt; a dramatic widow’s peak centered attention on eyes that were kind, but two clicks shy of forthright. But as he aged, as Chicago and the country grew wealthier and more refined, Algren became more disheveled and idiosyncratic, as if in defiance of the times. He grew a gut and took to wearing polyester pants, often unzipped. If he spilled gravy on his tie, he dashed salt on it as well. And when a young fan sought him out to discuss literature and receive learned counsel, Algren met him at a bar, and the only advice he provided the young man in earnest was that he should visit the animal house at the Lincoln Park Zoo, and a girl named Candy who worked the corner of Kedzie and Sixteenth.

Much of Algren’s later work is brilliant, but he was never again a sensation and didn’t aspire to be one. He socialized with people he liked at the expense of people who could advance his career, and stopped taking himself seriously, at least outwardly. He began calling himself a journalist, and a “loser,” like Melville, and swore he’d never write another big book. When asked, he framed his new life the way his father would have framed his, if he had ever felt the need to explain himself. “If I could get by without writing, I’d be very happy,” he told an interviewer. “I write for financial reasons. I don’t figure I’m changing the world… I’m satisfied with this trade, which I do very easily—and because there’s really nothing else I can do.”

Most of that was bluster, designed to protect himself from the sort of criticism that had nearly killed him twice. Algren did see himself as a tradesman, but he did more than make a living; he kept creating literature, as he defined it. In 1964, he published a sort of sloppy autobiography called Conversations with Nelson Algren. And he wrote two travel books, Who Lost an American? and Notes from a Sea Diary, in ’63 and ’65, respectively. In ’73, a collection of Algren’s magazine writing, essays, and short fiction was published as The Last Carousel. These later books were uneven—sometimes lazy, often brilliant—but not one of them elided Algren’s conviction that it was his responsibility as a writer to challenge authority with “conscience in touch with humanity.”

Algren was still living in his West Evergreen flat in 1974 when the American Academy of Arts and Letters called to say it had voted unanimously to present him with the Award of Merit for the Novel—an honor shared only with Dreiser, Mann, Hemingway, Huxley, O’Hara, and Nabokov. He was in his mid-sixties, almost retired, and unwilling to become excited by an honor that would not enhance his ability to publish. Algren accepted the award graciously, in writing, but on the day of the awards ceremony he lectured to a garden club in Chicago. Years later, when Kurt Vonnegut, a friend and member of the Academy, asked what happened to the medal, Algren said it must have “rolled under the couch.”

Algren spent part of 1974 in Paterson, New Jersey, on assignment for Esquire. The magazine wanted a story about Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, a middle-weight boxer who had been convicted of multiple homicides. Carter’s guilt was unquestioned at the time, and Esquire wanted an Algrenesque piece about the psychology of a murderer. After reporting the story, Algren wrote a feature suggesting Carter’s innocence. Esquire rejected it on those grounds, and in so doing delivered Algren his last lost cause.

Despite his recent award, by 1975 Algren was sinking ever deeper into obscurity. Chicago was no longer the “drafty hustler’s junction” he had helped define, and few people living in the affluent present were interested in Algren’s tales of the shabby past. Though he had, during his travels, found his books in libraries in Asia and Europe, he couldn’t find a single one in Chicago’s main library. And when Playboy hosted a Chicago writers’ conference, he wasn’t even invited. Using the Carter case as his cover, Algren decided to leave the only city he really knew and exile himself to Paterson, a city he could still understand. Shortly after leaving Chicago, Algren was caught on camera at a party, deadpanning with Studs Terkel about his move. “Downtown Paterson is really… something you shouldn’t see after midnight,” he says. “It’s my kind of town. I like it, I like it.”

Four years into his exile, Algren, by then a poor old man, had a heart attack, which he hid from his friends. He had started shopping around a nonfiction book documenting the miscarriage of justice in the Carter case, but no publisher wanted journalism from Algren, they wanted fiction. He rewrote it as a novel, but when the time came to part with the manuscript, he refused to sell for the amount he was offered. (It was eventually published posthumously.) Hurting from rejection, sick from a bad heart and a shelved book, with no projects on the horizon, Algren left Paterson to enter unofficial retirement in Sag Harbor, Long Island.

Algren rented a small bungalow hard by the Atlantic, and kept his writing desk clear. Free from the pressure to outwrite his younger self, he was happier than he had been in decades. He spent weekends holding court at a small local bookstore, and reconnected with Kurt Vonnegut, who introduced him to Peter Matthiessen. Betty Friedan lived across the street, and often drove Algren around in a hundred-dollar wreck of a car that once spilled him onto the street when she took a sharp turn.

Fat and happy was how the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters found Algren when they called in February 1981, this time to say he had been inducted as a full member. It was an honor he had felt entitled to for decades, and however belatedly, it returned him to the spotlight. A German press bought his book about Rubin Carter, as well as the rights to republish all his major works. And the New York Times and Newsday called for interviews. “I’m going on half a century in this ridiculous business,” he said. “You know, Hemingway said the main point is to last. And I guess I’m still here,” he finished, with his signature mix of spite, pride, and self-effacement.

Algren had often compared himself to Melville, who had been “banished” for writing Moby-Dick and died earning less then twenty-five dollars a week as a customs inspector. Like Melville, Algren insisted, he would be denied the recognition he deserved from the literary establishment during his lifetime.

And he was right, if just barely.

On May 8, 1981, Algren felt chest pains. He visited a doctor, who insisted he check in to the hospital for observation, a demand Algren refused. He was hosting a party to celebrate his induction into the Academy the next day, and he was not going to miss it. That night he gave a long, stressful phone interview. A few hours later, at 6:05 a.m. on May 9, he had another heart attack, this one deadly. There was no will and no known next of kin. Algren’s body went unclaimed for two days. Chicago friends, not knowing who else to contact, called Joe Pintauro, who had known Algren well for only a year, to express their sympathies. Candida Donadio, Algren’s agent, had to order the headstone, and when it arrived, Algren’s name was misspelled. His name is correct on the replacement, which sits on a plot near the edge of the cemetery, chosen by Pintauro so Algren could be “near the people.” And below his name is an epigraph perfect for a man who preferred fighting to winning, and gambled without regard for the consequences: THE END IS NOTHING. THE ROAD IS ALL. [9]

- I can imagine a challenge to the number of Algren’s books I’ve chosen to count, to say nothing of my assessments. I am including every book completed while he was living. Two of them, Nonconformity and The Devil’s Stocking, were published after his death but completed before he died. I am not counting two posthumous collections of his writing, The Texas Stories and Entrapment; the collection he edited (Nelson Algren’s Own Book of Lonesome Monsters); or Conversations with Nelson Algren, a book-length autobiographical interview that was published in 1957. I am also not counting America Eats, a gastronomical book he wrote on assignment for the WPA. It was not published during his lifetime, and he didn’t want it to be. ↩

- From “Tricks Out of Times Long-Gone.” ↩

- I owe a debt to Bettina Drew for her excellent biography, Nelson Algren: A Life on the Wild Side. Since it was published, in 1989, little has been added to the record that significantly contradicts its assertions. The essays “Nelson Algren’s Last Year: ‘Algren in Exile’” and “The First Annual Nelson Algren Memorial Poker Game” offered additional insight into Algren’s character and are well worth a read, as are “Nelson Algren: The Iron Sanctuary” by Maxwell Geismar, and “A Voyeur’s View of the Wild Side: Nelson Algren and His Reviewers” by Lawrence Lipton. ↩

- On the evening of January 25, 1934, before leaving Alpine, Algren entered Sul Ross, wrote for fifteen minutes, and then placed a cover on the typewriter he was using and walked out the door with it. Later that night, after being arrested a few miles outside of town, he made the pitiable confession: “I wanted a typewriter very bad because I am a writer by profession, I’ve never owned a typewriter of my own.” He was in jail almost a month and was freed very near his deadline. ↩

- Over the course of more than two decades, Kontowicz and Algren would break up three times and marry twice. Amanda was a remarkable woman but, no matter her virtues, Algren treated her through the decades in the careless way he treated most women. He needed affection, and longed for stability in an abstract way that reality never could measure up to. Each time he moved in with a woman he quickly became indifferent, listless, and absentee, longing to be able to write through the night and gamble for days without answering to anyone. ↩

- There is no way to avoid mentioning that Algren and de Beauvoir became lovers, but I don’t have space to do their relationship justice so I won’t try. They had a long-distance love affair that lasted many years; readers interested in the details can find many in the books The Mandarins, America Day by Day, and A Transatlantic Love Affair: Letters to Nelson Algren. ↩

- There is dispute about whether he ever joined the Communist Party. It is unquestionably true that he considered himself a communist for a period of years, and spent considerable time at meetings of the John Reed Club. The FBI claimed Algren had been a card-carrying member of the CP. Algren himself denied this, but never took the matter to trial, maybe to avoid perjuring himself. The truth of whether or not he signed a card and paid dues seems lost to history. I state here that he was a communist because he referred to himself that way (“I went into the Communist movement,” he says in Conversations with Nelson Algren), and because I am inclined to think well of anyone who joined the CP during the Great Depression and left when they got a sense of Stalin, and I think well of Algren. ↩

- Two writers, a world champion boxer, a fictitious bartender, a philosopher/writer, and an infielder, respectively. ↩

- This quote is often attributed to Willa Cather, but it belongs to Jules Michelet. One of Cather’s characters in Old Mrs. Harris, a novella published in 1932, quotes Michelet in the original French and then translates. The phrase has evermore been attributed to Cather, who often used it in her speech. ↩