The construction of a crossword consists of two operations that are quite different and in the end perfectly independent of each other: the first is the filling of the diagram; the second is the search for definitions.

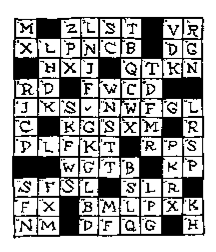

The filling of the diagram is a tedious, meticulous, maniacal task, a sort of letter-based arithmetic where all that matters is that words have this or that length, and that their juxtapositions reveal groupings that are compatible with the perpendicular construction of other words; it is a system of primary constraints where the letter is omnipresent but language is absent.1 Contrariwise, the search for definitions is fluid, intangible work, a stroll in the land of words, intended to uncover, in the imprecise neighborhood that constitutes the definition of a word, the fragile and unique location where it will be simultaneously revealed and hidden. The two operations imply mental faculties that could almost seem contradictory: in the first, one proceeds by trial and error, starting over twenty or thirty times a grid that one always deems less than perfect; in the second, one favors intuition, fortuitous finds, sudden illumination; the first is done at one’s table, with obstinacy and tenacity, groping, counting, erasing; the other is rather done at any hour of day or night, without thinking about it, strolling, letting one’s attention float freely in the wake of the thousand and one associations evoked by this or that word. One can very well imagine—and one sees this sometimes—a crossword composed by two cruciverbalists, one of whom would supply the diagram, and the other the definitions.2 In any case, the two operations are almost always separate: one starts by constructing the diagram (generally starting from the first word across or down—which constitute what is called the gallows—chosen in advance because of a definition deemed felicitous), and it is once the diagram is completed that one starts to seek definitions of the other words it contains. Not only words, alas, but also groups of two, three, four letters, or even sometimes more, which, in spite of the author’s efforts, persist in not spontaneously offering any known meaning.

1. Of Diagrams and Black Squares

As opposed to the English-language tradition, where the positioning of the black squares matters more than their number, French cruciverbalists favor diagrams that include as few black squares as possible.3 The perfect diagram should thus contain no black squares: all the letters should cross and between them form words with meanings. The following examples aim to demonstrate the great difficulty of such perfect crossings. Admittedly, it is not really difficult to construct a 1 x 1 crossword with no black squares:

Across

I. Vowel

Down

...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in