Song of the lyrebird

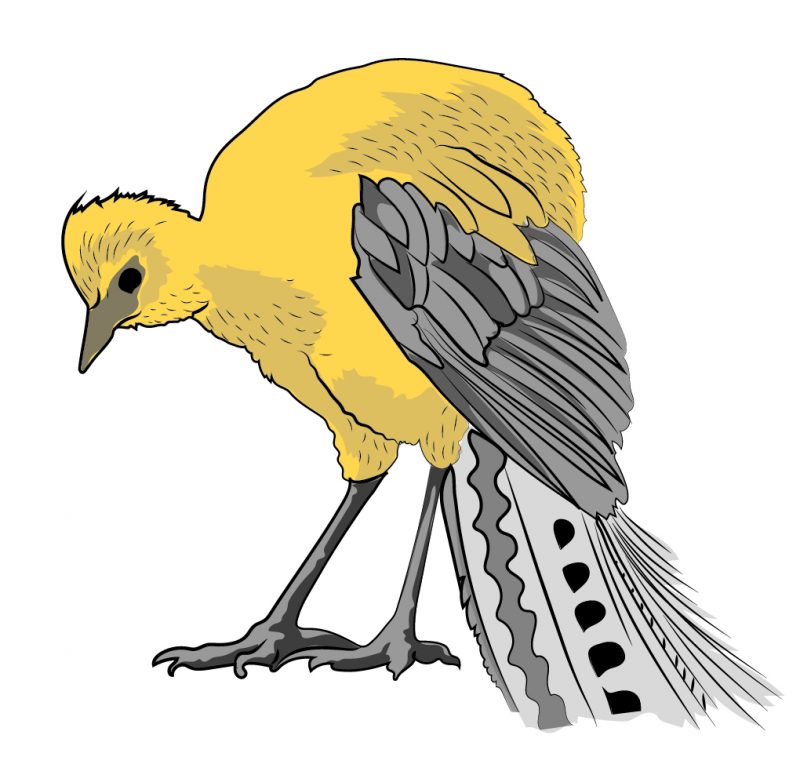

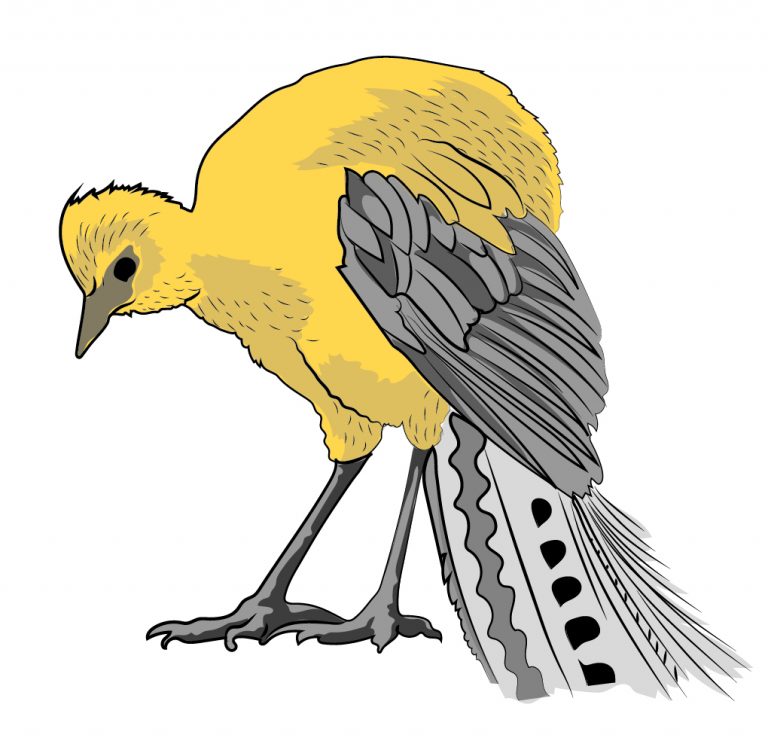

If you walk through the Daintree Rainforest in Queensland today and hear a baby crying behind a bush, it’s plausible that you’ll look and find no infant marooned there in the dirt, only a lyrebird crying out for the mother of a species not its own. An Australian bird that sports a tail visually similar to the stringed instrument after which it’s named, the lyrebird can mimic sounds with incredible precision: magpies, chain saws, toy guns. Ornithologists have speculated that it may have no call of its own, and that its most common song could be one copied from a genus now extinct.

The way writers mimic reality is similar. A realist working in the style of Zola, say, may replicate historical details to make a nineteenth-century Parisian pâtisserie appear identical to the one where Jules Verne ate bonbons. But just as no bird can be a human’s baby, no text can actualize candy or restore the past. In this sense, mimicry, shackled to reality, is a lie. But mimicry plus imagination, Brazilian writer Luiz Costa Lima argues in Control of the Imaginary: Reason and Imagination in Modern Times (translated by Ronald W. Sousa), can operate in its own separate, self-contained reality, and can lead toward a better grasp of this one. Defining fiction as a critical use of the imaginary, an actualization of what’s absent from reality, Lima examines how the writer who acknowledges her relationship to the conditioning powers of society can use mimicry to make fiction into a laboratory for testing and understanding the real world.

Lima doesn’t use the term mimicry but rather mimesis, an art term defined by philologist Ingemar Düring as a reproduction or imitation of the “sensible world.” Referencing the Greeks, Lima distinguishes mimesis—a copy of a thing’s “internal potentialities”— from mere imitation. A mimetic copy exists in the plane of the imaginary, not in the sensible world; it appears similar to its source but has its own autonomy as well. It has transcended imitation and become a form of expression.

Saint Augustine, no big fan of art, writes in On Care to Be Had for the Dead about a student of rhetoric who comes across “an obscure passage of which he could make no sense. In his irritation,” Augustine explains, “he had to use every device he knew to fall asleep. I then...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in