For close to fifty years, Juan Goytisolo has been one of Spain’s most celebrated writers, although Goytisolo doesn’t see much to celebrate about Spain. In fact, most of his work revolves around his passionate rejection of traditional Spanish culture. Yet the Spanish can’t get enough of his incisive critiques of sexual conventions or of Spain’s disconnect with the Arab world across the Atlantic in Morocco, where Goytisolo prefers to live.

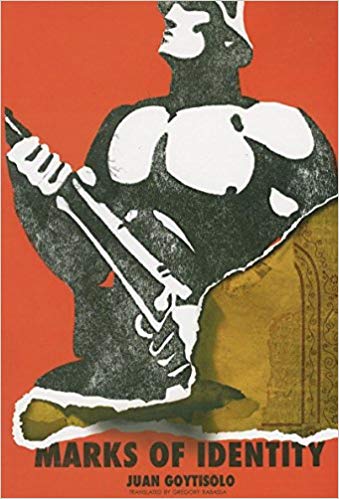

In one of his strongest novels, Marks of Identity, deftly translated by Gregory Rabassa and recently reissued by Dalkey Archive Press, Goytisolo follows the wanderings of several characters whose lives are irrevocably altered by the Franco regime. His iconoclastic impulse shapes the novel at every level. Even the structure of the writing is a protest against what he once called the “tyrannical conception of genre” in a 1984 interview published in the Review of Contemporary Fiction. Goytisolo wrote Marks of Identity nearly two decades before the interview, and the intervening years led to books increasingly varied in format, though not all as successful as this one.

The sprawling chapters of this early novel shift from dialogues to free-verse poetry to the notes of spies following various characters suspected of communist activity. The constant shifting makes for a disjunctive, jumbled sort of reading experience, but the chaos seems integral to Goytisolo’s vision of the haphazard nature of life in exile. The novel’s protagonist, Álvaro, like Goytisolo himself, moves to Paris after Franco’s rise to power. Intermittently, Álvaro reconnects with friends still living in Spain to hear of the other life, “the one that had gone on without him after the already remote date of his departure.”

Goytisolo chronicles how Álvaro’s efforts at love and meaningful, idealistic work are thwarted again and again as he shifts from one temporary home to another. The accumulating impact of all these futile attempts at constructing a life leads to a few crushing moments of reckoning that anchor the book. Goytisolo’s writing is at its most luminous in these passages, where Álvaro and his friends from the pre-Franco era get together to mourn their disappointments and rehash “the period against which they had fought without success, from which they had tried to flee and which had ended up devouring them.” Goytisolo has a talent for statements like this, summing up his generation’s shared disappointments. His sentences, like his novels, tend to be long, unpredictable in their constructions, and packed with a bewildering mix of gorgeous imagery and moral indictment.

In other novels about the fate of intellectuals in the wake of dictatorship, such as Roberto Bolaño’s Distant Star, or José Donoso’s The Garden Next Door, there are usually some small moments of redemption. Not so in the work of Goytisolo, yet the vividness and lyricism of his descriptions serve as a sort of consolation. In a Spanish fishing village, two friends of Álvaro’s go out on a boat to hear news of who has disappeared and been killed since their last visit before Franco came to power. When they get to the dock, there is a floating “smell of emptiness and death mixed with the discharge of brine, odors of pitch, and a faint emanation of tar.” This novel of Goytisolo’s could be described much like that dock. The difficulty of conversation in an era of constant surveillance becomes as palpable as the smell of brine and tar.