The woman looks into the camera with an expression somewhere between contentment and apathy. With her thick brown hair and floral dress, she could pass for Party of Five–era Neve Campbell, or a blowsier Natalie Merchant. She is holding a sign on which she has written in Magic Marker: IT’S OK FOR YOU TO THINK I’M NOT OK BUT I AM. Nothing in the photo suggests the presence of a beverage, but it is, nonetheless, an ad for a soda.

The year was 1994—My So-Called Life, Kurt Cobain’s suicide—and the Coca-Cola Company, smarting from a recession, was attempting to reach a new demographic of disillusioned young people known as Generation X. The previous year, Coke CEO Roberto Goizueta had rehired Sergio Zyman, the Mexican marketing guru, despite the fact that his last brainstorm, New Coke, had nearly toppled the company. Nevertheless, Zyman was tasked with overseeing a new brand that would appeal to the MTV generation, one inoculated against the standard advertising language of shiny packaging and jingles.

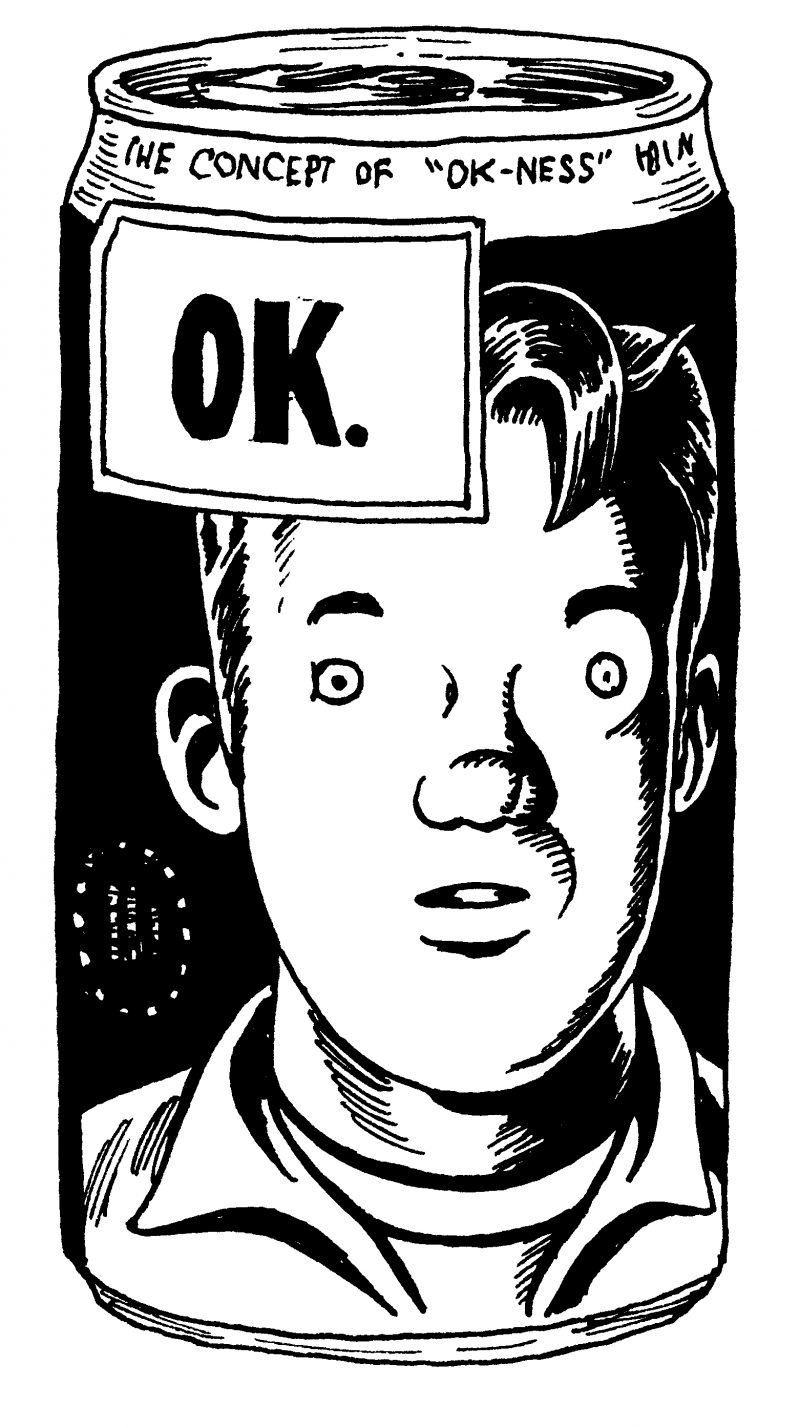

The result was OK Soda. As Mark Pendergrast writes in For God, Country, and Coca-Cola, “the drink was deliberately positioned to be blasé. It wasn’t exciting, delicious, or sexy. It was just OK.” Where other brands courted teens with empty promises—This sneaker will change your life—OK Soda appealed to their innate skepticism. “It underpromises,” one Coke executive, Brian Lanahan, told Time. “It doesn’t say, ‘This is the next great thing.’”

Depending on whom you ask, the product was either groundbreaking or doomed: a jaded soda marketed to people distrustful of marketing, with accompanying advertising designed for people who hated advertising. When it launched, Zyman predicted that OK Soda would garner a billion dollars and 4 percent of the US soft-drink share. But by 1995 it was off the shelves: another Zyman misfire. Twenty years later, it maintains a cult following, with old poster art fetching hundreds of dollars on eBay. What OK Soda represents is surely failure—of a giant corporation pandering to the margins—but the kind of failure so brazen, tone-deaf, and strange that its legend survives as a kind of marketing performance art, utterly endemic of its time.

When OK Soda was introduced, of course, Coke executives were certain they had it right. Drawing on a study from MIT, the company had pinpointed what Generation X was all about. “Economic prosperity is less available than it was for their parents,” Lanahan theorized. “Even traditional rites of passage, such as sex, are fraught with life-or-death consequences.” Tom Pirko, a Coke marketing consultant, told NPR, “People who are nineteen years old are very accustomed to having been manipulated and knowing that...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in