In the opening scene of L.A. Story (1991), weatherman Harris K. Telemacher—played by the film’s writer, Steve Martin—rides a stationary exercise bike in the middle of Echo Park, and captures, in voice-over, an ambivalence experienced by many middle-class, middle-aged Americans in the late ’80s and early ’90s: “I was deeply unhappy, but I didn’t know it, because I was so happy all the time.”

Martin was born in 1945, at the vanguard of the baby boom. His was the generation that spent its formative years being courted by advertisers, who wielded sufficient cultural clout to make the Beatles the Beatles, and hula-hooping a thing. Reaching adulthood in the throes of the Vietnam War, boomers swelled the ranks of the student-protest movement, bathed in the mud of Woodstock, and railed against an outdated establishment (which happened to be populated by their parents). As Ray Kinsella, Kevin Costner’s character in Field of Dreams (1989), says, “Officially my major was English, but really it was the ’60s.” Martin and Costner’s generation was convinced of the efficacy of civil disobedience and, like no generation before it, of the centrality of individualism.

The thing about young people, though, is that they grow up—and what becomes of a bunch of kids who sloganized “Don’t trust anyone over thirty”? By the 1980s, 3.4 million baby boomers found themselves surviving various stages of midlife and its particular torments: the death of one’s parents, the weight of responsibilities financial and familial, the winnowing of life’s possibilities. These sorrows bedevil mid-lifers in any decade, but the ’80s presented a unique wrinkle. The era was, after an initial slump, a boom time, and consumption was famously conspicuous—so a wide swath of boomers, both materially comfortable and professionally accomplished, watched themselves become the establishment they had once hoped to tear down. They moved to the suburbs, became Reagan Democrats, and acknowledged that the revolution had failed: government was still corrupt; American society, with its moral panics and televangelists, was enduringly uptight; and the idealism that boomers had once cherished had largely leached from their lives. They were deeply unhappy, despite being so happy all the time.

*

Mass psychological unrest has a way of trickling down, to borrow the locution of the period, and in the late ’80s and early ’90s, this conflict seeped into commercial film. There arose a micro-genre of sincere but funny existentialist narratives, all featuring boomer-aged protagonists who attempted to clarify what really matters and pinpoint how one ought to live. The most interesting of these existential-crisis films—call them “raison d’être dramedies,” or RDDs for short—include L.A. Story and Field of Dreams, as well as Peggy Sue Got Married (1986), Mr. Destiny (1990), Defending Your Life (1991), Groundhog Day (1993), and Heart and Souls (1993). In each, a boomer, usually dissatisfied, interacts with a magical or supernatural force and, as a result, arrives at a conclusion about the meaning of life. Many movies of the era dabbled in goofy fantasy—Back to the Future (1985), Weird Science (1985), and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989), to name a few—and others mined the supernatural for a sentimental wallop, like Big (1988) and Ghost (1990). But RDDs used their conceits to ponder philosophy’s basic question, the one a generation might suddenly need answered upon reaching an especially fraught middle age: what’s it all for?

Filmmakers have been compelling characters to learn from magic for decades. But the difference between magical-realism films of yore and those of the ’80s and ’90s was one of stakes: in the past, the starting point for the protagonist before his magic-fueled revelation was appreciably more dire. By the ’80s and ’90s, feeling vague malaise about a comfortable life was conflict enough to carry a narrative.

Consider that beloved proto-RDD, It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), in which George Bailey (James Stewart) delays his aspirations time and again to buoy the Bedford Falls Building and Loan, and nearly gets ruined and sent to jail for his trouble. By the age of thirty-five, George is so dejected that it takes a glimpse of a parallel universe to convince him against suicide. That done, he recognizes the value of what he has and vaults into ecstatic gratitude: “I want to live again. I want to live again. Please, God, let me live again.” George’s ultimate lesson is that his place has always been at home, where he is a quiet kind of hero. “No man is a failure who has friends,” the angel Clarence tells him in a letter.

But fast-forward forty years, and the protagonists aren’t so easily convinced. For the heroes of RDDs, it takes a whole lot more than Zuzu’s petals and the dewy Donna Reed to be fulfilled. The Capra ethos—that love and family are all one needs—is obsolete; most of these characters already have love and family, and they still aren’t happy.

*

It’s exactly this scenario that propels Mr. Destiny, which, of all the RDDs, owes the biggest debt to It’s a Wonderful Life. But where George Bailey sees his dreams derailed by external forces, Larry Burrows (played by Jim Belushi) has no one but himself on which to blame his disappointment. In 1970, on Larry’s fifteenth birthday, he had gone up to bat at the big high-school game, in (what else?) the bottom of the ninth, with two outs, loaded bases, and a 3–2 count. Larry swung, missed, and lost the championship. Though his screw-up won him love—Ellen Robertson, a girl from school, comforts him after the game and things proceed from there—by the time we meet Larry he’s spent twenty years obsessing over how things would have turned out if he’d hit the ball.

The film is set on Larry’s thirty-fifth birthday, which finds him in the town where he grew up, working at the corporate headquarters of the Liberty Republic Sporting Goods Company—in a rare bit of wit, the entrance to Liberty’s building features a giant sculpture of a looming baseball—and married to Ellen (Linda Hamilton), now a scrappy union organizer who’s standing up to the heartless fat cats on Liberty’s board. (The film attempts a subplot concerning some nefarious corporate machination or other, but I won’t trouble you with it.) Larry has a modest house in the suburbs, works with his lifelong best friend, Clip (Jon Lovitz), and, apart from the decrepitude of his station wagon, has little to worry about. Yet he wallows in regret—“My life is shit,” he says, then reconsiders: “It’s not that it’s bad, you know, it’s just that it’s ordinary”—and fantasizes about wealth, sports cars, and his boss’s sexy wife, Cindy Jo (Rene Russo).

Mr. Destiny has all the sophistication of a laugh-tracked sitcom, but it does an admirable job of establishing the dichotomy of Larry’s discontent—it’s foolish and self-indulgent, and yet it’s hard not to sympathize with it. Early on, Clip tells Larry, “Nothing’s ever good enough for you. Way I see it, you’ve got the perfect life. You’ve got a wonderful home, a terrific wife, a good job, and the best friend money can buy. What else could a guy want?” Larry replies, “A little excitement would be nice.” Yes, he’s whining—but he’s eaten Wheaties every day for two decades, has been with one woman since he was fifteen, and drives a crappy station wagon despite being childless. The guy has a point.

Luckily, excitement soon arrives: driving home from work, Larry’s car breaks down outside the Universal Joint, a bar tended by Mike (Michael Caine). While Larry waits for a tow truck, he pours his heart out about the missed pitch, revealing how badly he wishes things had gone differently, and how he knows they would have if only he’d gotten a solid hit. Mike pours Larry an opaque drink called Spilt Milk. (“It’s the one drink there’s no use crying over,” he says unnecessarily.) Suddenly, Larry’s wish is granted. His destiny has been altered. He hit a homer in 1970, won the game, and reaped the cumulative rewards: he’s rich, married to Cindy Jo, and is the president of Liberty.

When George Bailey glimpses the world in which he never lived, he learns that he’s played a greater role in people’s lives than he realized. When Larry Burrows sees the world in which he played a better game of baseball, he learns that he’s kind of a rube. He enjoys a hot night with Cindy Jo, but doesn’t much want to accompany her to the opera; he asks his butler for “a brewski” and is met with bewilderment. He misses Ellen, but because he’s now one of the fat cats, she hates him. Clip, a disgruntled Liberty cog, is suicidal. (We don’t ever really learn why; it’s probably just as well.) Larry manages to convince Ellen to go on a date with him—conveyed to the viewer in a montage that makes terrific use of the Spencer Davis Group’s “Gimme Some Lovin’”—during which he realizes just how heartbroken he is to have lost their humble, happy life. Just as George begged Clarence to “get me back,” Larry makes his way to the Universal Joint to whip up a batch of Spilt Milks. He was never meant to hit that ball. He was always supposed to miss—so Ellen could comfort him, and so his life could be the imperfect delight it has been for twenty years. He mixes the concoction, heads home, and finds that Ellen, his wife once again, has thrown him a surprise birthday party. All is right with the world.

Our lives, according to the logic of the Mr. Destiny universe, are predetermined. A divine hand—in this case that of Michael Caine, the titular mister—guides us toward our truest, most fitting life, and all we have to do is show up and live it. How comforting! This philosophy absolves us of responsibility for our failures, rewards us (and Jim Belushi) for settling for way less than we want. It also bears a striking resemblance to the circumscribing takeaway of It’s a Wonderful Life, which is that a good-enough life is exactly that. Apply that thinking—rather, the need to believe that thinking—to the great boomer psyche-slump of the 1980s and ’90s, and doofy Mr. Destiny starts to feel less like a dim comedy than a wrenching tragedy—like a generation declaring, “We tried, we failed, and this is as happy as we’re ever going to get. Bring on the brewskies.”

*

The role of romantic love remains fairly static across RDDs. In almost every case, it propels the narrative but is incidental to the mysterious universe’s mysterious lesson; typically, romance serves only as the mechanism to let you know the lesson that has sunk in. That’s certainly true of Groundhog Day, in which dissatisfied jerk Phil Connors (Bill Murray) is forced to live the same day again and again, trapped in a netherworld of crushing repetition. Once Phil decides to start using these do-overs for good—changing strangers’ tires, buying a pair of lovebirds tickets to WrestleMania—and transforms himself into a nice guy in the process, he wins the heart of Rita (Andie MacDowell), along with the privilege of once again living sequential days. Phil stops being a putz, and a happy life with Rita is his reward. It’s the same in Heart and Souls, in which work-obsessed commitment-phobe Thomas Reilly (Robert Downey Jr.) is followed by four ghosts who use him to tidy up their unfinished business, a process that inspires Thomas to finally give his long-suffering girlfriend, Anne (Elisabeth Shue), his heart. She’s thrilled—but it’s Thomas who has been transformed, even saved.

Peggy Sue Got Married disrupts this incidental-romance dynamic, making the love story the driving force of the film. Peggy Sue Kelcher (Kathleen Turner) and Charlie Bodell (Nicolas Cage) had been high-school sweethearts, but when the film opens, on their twenty-fifth class reunion, the couple is estranged in light of Charlie’s infidelity. Unfortunately for Peggy Sue, Charlie shows up to the reunion anyway, ratcheting up her anxiety and forcing her to answer their friends’ questions about the terminal state of their marriage. When Peggy Sue, reduced to panicked tears, is crowned queen of the reunion, she faints—and wakes up in 1960, seventeen again, her friends de-aged, her grandparents alive, her sister a child, her life rewound. She maintains, however, her awareness of herself at forty-three, negotiating her high-school redo with the wry knowingness of adulthood. After blowing off a math quiz, Peggy Sue firmly assures the teacher she will never again have use for algebra—“and I speak from experience.”

During her return to adolescence, Peggy dodges Charlie’s affections to go enjoy the things she regrets not enjoying enough—her beloved grandparents; her sister, who in the 1985 reality has grown distant; and sex with the intense beatnik she always had the hots for but never pursued. (When she does, he quotes Yeats as foreplay. It’s pretty great.) But before long, Peggy Sue is embroiled in the Charlie love-tempest all over again, frothing at him with the residual rage of a cheated-on forty-three-year-old quibbling over mortgage payments, and yet falling for him (again) despite herself. What Peggy Sue accomplishes in her trip through time is not so much an overhaul of her worldview as a reaffirmation of her choices: she cannot turn away from this man, even if she wanted to.

There’s a larger cultural reading here. In 1990, fewer than one in ten American divorces occurred among the middle-aged—which suggests that, unless boomers figured out some secret to making love last, they found a way, a reason, a rationalization, to persevere, even when their marriages weren’t working. (That didn’t last, though; boomer divorce rates have since doubled.) So when Peggy Sue returns to 1985 and decides, after her taste of young love, to reconcile with Charlie, it’s less a personal choice than a concession to cultural norms. It’s worth noting that among Peggy’s friends at the reunion she’s the only one whose marriage has failed. Once again, the film’s drumbeat calls for compromise. Settle, it says. The glory days are in tatters, but enjoy the scraps as best you can.

*

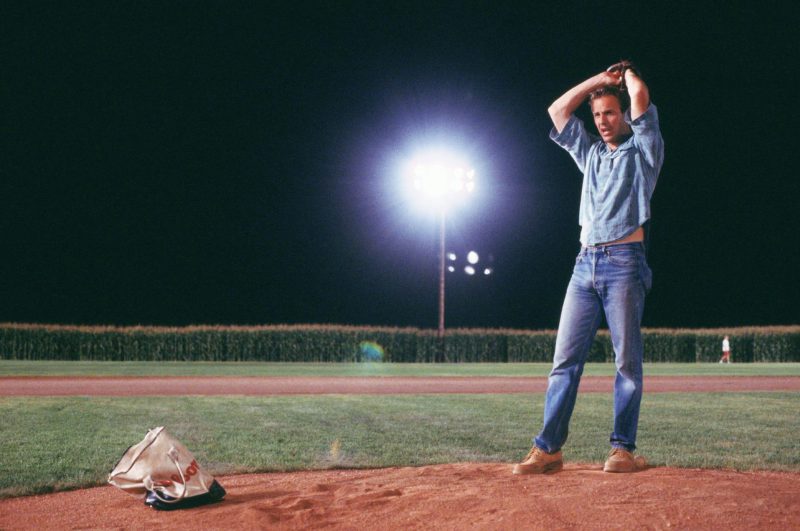

There are, however, RDDs with happier endings—happier not simply because things work out nicely for the protagonists but also because the larger takeaways are as positive as they are instructive. The imperative to make one’s life what it ought to be—and to forgive and transcend one’s imperfect childhood—is the thrust of Field of Dreams. Ray Kinsella, thirty-six, a married father of one who is working, improbably, a few dozen acres of fertile Iowa farmland, misses the passion of the 1960s—the period he “majored in.” He and his wife, Annie (Amy Madigan), both graduates of UC Berkeley, retain faint glimmers of their idealistic youth; in one scene, Annie upbraids a local reactionary for demanding that a book be censored from the town’s schools, chalking up the woman’s intolerance to her having missed out on the ’60s: “I think you had two ’50s and moved right on into the ’70s,” Annie spits out. Ray compounds his ’60s nostalgia with regret related to his father, John Kinsella, a man who deserted him as a teenager, whom he is terrified of becoming, and whom he “never forgave for getting old.”

You know what comes next. “If you build it, they will come,” a voice whispers to Ray, following up the transmission with a vision of a ball field in the middle of his crops. Ray is startled—every RDD includes a requisite stretch of incredulity once the supernatural makes itself apparent—but he can’t shake the conviction that he must decipher and carry out the voice’s instructions. While pondering his next move, Ray finds his daughter, Karin (Gaby Hoffman), watching, not coincidentally, the 1950 film Harvey, starring our old friend James Stewart. The film, a pre-RDD imaginary-friend picture, concerns a grown man whose closest confidante is an invisible six-foot-tall rabbit. “The man is sick,” Ray says to his child. Nonetheless, he heeds the voice, builds a pro ball field, which requires plowing under a considerable portion of his corn, and soon faces foreclosure on the no-longer-profitable farm.

But who cares, when you’ve got the ghost of Shoeless Joe Jackson (Ray Liotta), the ballplayer idolized by Ray’s father, hitting curveballs in your front yard, accompanied by several members of the 1919 White Sox—the eight men kicked out of baseball after allegedly throwing that year’s World Series. They’ve come to the field to be redeemed, to play the game they loved and lost. Now that “it” is built, Ray believes, “he”—meaning Shoeless Joe—has come. But then the mysterious voice re-ups with a new command: “Ease his pain,” it says. Ray wonders the obvious: whose?

Another vision provides the answer. In the ’60s, Terence Mann (James Earl Jones) was a writer, intellectual, and baseball lover who, after coining the slogan “Make love, not war”—and writing a story about a character named John Kinsella—retreated from public view. When Ray shows up on Terence’s Boston doorstep to drag him to a Red Sox game, as his vision has cryptically instructed, Terence makes explicit his—and his generation’s—grief over the failure of their heyday to bring about real change. “I was the East Coast distributor of ‘involved.’ I ate it, drank it, and breathed it,” he says. “Then they killed Martin, and Bobby, and they elected Tricky Dick twice, and now people like you think I’m miserable because I’m not involved anymore. Well, I’ve got news for you. I spent all my misery years ago. I have no more pain left for anything.” We tried; we failed; this is as happy as we’re ever going to get.

But Ray isn’t one to entertain fatalism. He drags Terence to the game, where he sees another vision and hears the voice yet again—“Go the distance,” it says—which leads to yet another trip. This time Ray must haul his hippied-out VW van to small-town Minnesota to pick up and make amends for the ghost of Archie “Moonlight” Graham (Burt Lancaster), who blew his one and only at-bat in the majors and subsequently quit baseball. But we’ll fast-forward past all that, because the field of dreams in Field of Dreams does not belong to Archie, nor to Terence, nor even to Shoeless Joe. The “he” in “If you build it, he will come” turns out to be, has always been, John Kinsella.

“Is this heaven?” John asks.

No, Ray says, “it’s Iowa”—but he’s wrong. Earlier, John Kinsella said that heaven is “where dreams come true.” Which means that Ray—standing in his ball field with his father, his wife and daughter preparing dinner up at the house, his passion reinvigorated, a long line of people arriving to pay him for the chance to relive the best things about our shared history (“The memories will be so thick they’ll have to brush them away from their faces,” Terence says)—is about as close as any of us can hope to get. Maybe boomers did fail. But the fire that made them what they were has not gone out. If you want to preserve your idealism and believe in something, then get up and do so. Go the distance. Ease your pain.

*

Fear is a curious theme when it comes to RDDs, because it often manifests as something else. Typically in these films, fear translates as lack of backbone or commitment (as in Heart and Souls), or as panic and rage (as in Peggy Sue Got Married), or as an array of lighthearted neuroses—which is certainly the case in Defending Your Life and L.A. Story, headed up by Albert Brooks and Steve Martin, respectively.

Defending Your Life is a departure from most RDDs, because the protagonist is dead. Yet that fact serves only to bring his need for a life lesson into sharper relief: he’s about to answer for his failures of character in a kind of cosmic court. On his birthday, ad exec Daniel Miller (Brooks) treats himself to a new sports car. While driving it home, blasting Barbra Streisand’s “Something’s Coming,” he loses his focus on the road and veers into the path of a bus.

The next scene finds Daniel in a white, toga-like robe, placidly riding a tram through a sunny, anodyne metropolis. (The film was shot in Southern California.) Having died in the accident, he has been transported to Judgment City, the bureaucratic hub of the afterlife. Here, everyone who dies becomes a defendant in what is literally the trial of their lives: they sit before a pair of judges who examine scenes from their time on earth in order to determine whether they will return to try again or “move on,” a nondenominational euphemism, it seems, for “go to heaven.” On what criterion is this judgment based? It’s not your ambition, good works, or the number of people who loved you. The measure of your life’s success is the degree to which you have conquered your fears. And so if, in the realm of RDDs, fear equals neurosis, you can imagine how well an Albert Brooks character might fare.

But in the few days before the verdict is handed down, Daniel manages to enjoy himself. He meets the vivacious Julia (Meryl Streep), who is spending her judgment week in an upscale hotel that leaves chocolate swans on one’s pillow at turndown; Daniel is holed up in purgatory’s answer to Motel 6. “I’m at the Continental,” he tells Julia. “Come over one day, we’ll paint it.” In this and other ways, he discerns that his verdict isn’t going to be good. Meanwhile, it’s clear that Julia, with whom Daniel has fallen in love, and whose trial footage shows her saving her children from a burning house and then returning to save her cat, will be “moving on” without him.

Just before their time in Judgment City comes to an end, Julia invites Daniel to spend the night with her—and though his cowardice has just been thoroughly revealed to him on the big screen, Daniel chickens out. At trial the next day, this spinelessness is what convinces the judges to send him back to earth. Daniel’s fear has won.

Rarely does a film end so satisfyingly; in fact, the last scene of Defending Your Life is so winning I’m loath to reveal it. But I will: as Judgment City’s ubiquitous trams begin to cart Daniel and Julia off to their opposite fates, they catch a final glimpse of each other across the tarmac. Daniel, overcome, unclamps his flimsy seatbelt, pries open the people-mover’s doors, runs across a half-dozen lanes of traffic, gets electrocuted by Julia’s tram, and pounds his fists on the Plexiglas door that separates them, shouting her name. “I won’t let you go!” he cries. “Open this up! Damn it, open it up!” Cut to the trial room, where the judges are watching it all unfold. The doors slide open and Daniel and Julia are reunited, allowed to move on together.

It seems like more than coincidence that this film was made in the late ’80s; conquering fear took on a different weight in an era of mortal terror. The AIDS crisis of that decade cast a frightening pall over the nation, inspiring panic rarely seen in the modern era. Americans were convinced the disease could be caught from toilet seats, handshakes, coughs. Its presence in the news—and its staggering death toll—served as a constant, crushing reminder that the old days of free love were long gone. In fact, fear of AIDS is precisely Daniel’s (disingenuous) rationale when the judges ask him why he declined to spend the night with Julia: “You must remember that on earth right now they’re filling our heads with all these terrible things. They keep telling you over and over that you’re not just sleeping with one person, you’re sleeping with everyone they’ve ever slept with.” Daniel is full of it, but that doesn’t mean his earthly counterparts—i.e., the viewers of the film—couldn’t sympathize with his faintheartedness.

*

L.A. Story also thrums with a keen awareness of mortality. Harris K. Telemacher is not yet dead, but death is often in his thoughts. When last we left him, he was riding the exercise bike in Echo Park, explaining his condition of sad happiness; the first leg of L.A. Story offers telling explanations for the same. First off, Harris lives in Los Angeles, a place herein depicted as a dreamlike realm of dichotomies, where idiosyncrasy flourishes in a wider context of homogeneity, one encounters rage and beauty in equal measure, and insincerity is a kind of religion. In a scene-setting montage set to Charles Trenet’s strange and sonorous “La Mer,” a row of neighbors retrieve their morning newspapers in a grinning, synchronized, absurdist ballet; a man walks down the street in flip-flops, carrying a Christmas tree; and a crosswalk sign reads uh, like, walk, and then, uh, like, don’t walk. That anyone manages not to feel at sea in this city starts to seem miraculous.

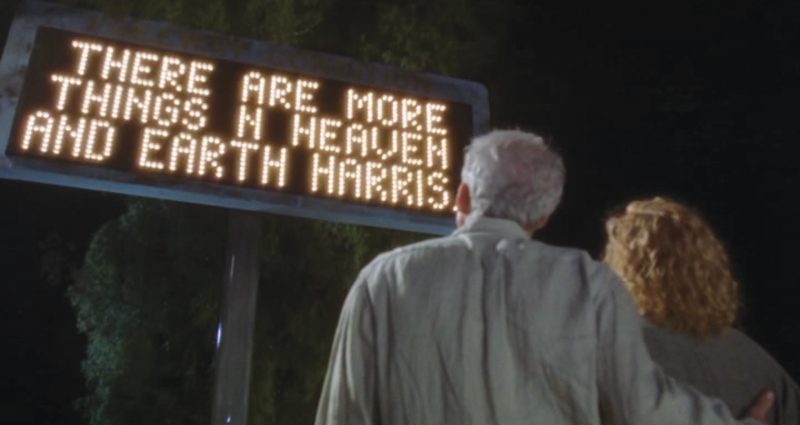

The arrival of a doe-eyed, eccentric, tuba-playing Brit named Sara (Victoria Tennant, at the time Martin’s wife) changes everything. At a group brunch rife with telltale nose-job bandages and showbiz blather, Sara is the only person capable of saying anything real. As the crowd orders a barrage of half-caffs and double espressos—“with a twist of lemon!” everyone chirps—Sara laments her long plane ride from London, but explains that “it’s nothing some sleep and a good fuck couldn’t cure.” Everyone is horrified, but something in Harris shifts; he’s thrilled by this unfamiliar taste of genuineness. Harris and Sara soon strike up a friendship, albeit one spring-loaded with romantic frisson. Then Harris makes another friend. Driving home one evening, his car breaks down, and when he pulls to the side of the road, he notices the huge freeway sign attempting to get his attention. Of all the RDD protagonists, Harris K. Telemacher may be the quickest adapter. hiya, its screen reads. “Hi,” Harris says tentatively. r u ok? the sign asks. “Yeah, I’m fine,” Harris says. i c people in trouble and i stop them, the sign says. “How am I in trouble?” Harris asks. The answer is clear, though. Harris is in trouble in the same way all of us are, is afflicted with the same fatal disease we all have: life. His chances of wringing any real joy out of his own are becoming increasingly remote.

One day Harris and Sara wander into a cemetery, where a gravedigger, played by Rick Moranis, readies a burial plot. In the hole is the skull of a long-dead man, and Harris holds it to his face and marvels: “I knew him.” The skull turns out to be that of a magician with whom Harris was once acquainted. The Yorick moment gets more explicit when Sara takes up Hamlet’s speech: “A fellow of infinite jest?” she asks. “Where be your gibes now? Your flashes of merriment that would set the table on a roar.” Harris holds his friend’s skull, staring down death in the middle of paradise. “Come back,” the gravedigger says as they leave. “They all do.”

There’s one known method for getting the better of thoughts of mortality, and this method is called living well. Just as Ray Kinsella listened to the unaccountable voice and went the distance—and just as Phil Connors and Thomas Reilly became better, kinder men; and just as Daniel Miller ran across tram traffic to live the life (er, death) he was always supposed to—Harris K. Telemacher finds his way to truth, to genuineness, to Sara. Unhappy happiness is no longer good enough. He will fight for what he loves. LA wants to help him? He wants to help himself. When Harris stops by the sign, victorious—and with Sara in tow—to tell it how everything worked out between them, the sign proffers another quote from Shakespeare that might well be the motto for every RDD. It says, there are more things n heaven and earth harris, than are dreamt of n your philosophy.

And isn’t it remarkable, in these films, when these “more things” touch down briefly on our humble planet to tell us what to do! The generational feelings that gave rise to these movies were ones of impotence, of disappointment, of the awfulness of letting oneself down, screwing it all up, selling out. When boomers felt they could no longer steer themselves, they fantasized on-screen about the big answers materializing from the great beyond, from a disembodied voice, from Michael Caine, from a freeway sign. Just so long as they came.

Say what you will about the cultural trend toward self-absorption that famously arose in the ’70s—“the me decade”—and that took permanent, ubiquitous root in the ’80s; say that this inward gaze gave rise to the worst kind of white-bread, head-up-its-ass, Big Chill–flavored ennui, whiny complaints about fabulous problems to have, the most inane brand of navel-gazing the nation had, at the time, ever seen. (We’ve more than topped it in the decades since.) That may all be true. But the questions of how to live, why to live, what life means, have been played with in entertainment since before the ancient Greeks. What waxes and wanes is the urgency with which we as a culture seem to need these questions answered, and in the ’80s and early ’90s the existentialist moon was full.

Some of the answers these films came up with, frankly, sucked: settle; don’t bother trying to be a success; accept your failures and keep right on failing. Give up, in other words. But their other proclamations were pretty great. Be kind, they said. Be brave and sincere. Believe in something. Fall in love with someone deserving of your affection. Make your life better. Hang on to your idealism, and let go of your baggage—especially the stuff your parents saddled you with. Grow up. Which is to say, live with your choices, and move on to make new and better ones.

Not too shabby, really.