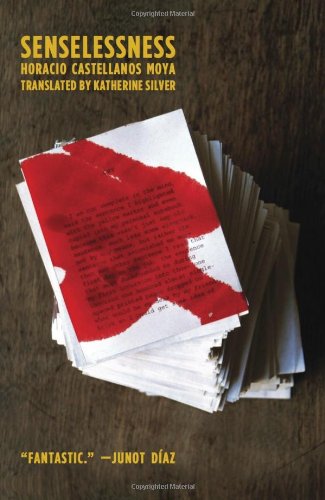

In 1998, a Guatemalan bishop was poised to release a thick report accusing his own government of all but genocide in the “scorched earth” campaigns of the early 1980s. Since then, a number of Guatemalan authors have imagined exiles returning to confront the bloody past. Horacio Castellanos Moya, a Salvadoran journalist who now lives in Pittsburgh, tells a narrower story in his intemperate seventh novel, Senselessness. In a thinly veiled version of Guatemala, he imagines just such a report driving its jittery proofreader insane.

The result is like Kafka on amphetamines. “I was about to stick my snout into someone else’s wasps’ nest, make sure that the Catholic hands about to touch the balls of the military tiger were clean and had even gotten a manicure,” the proofreader tells us shortly after agreeing to correct the 1,100-page report. He is right to be concerned, but his paranoia soon takes on a life of its own. Walking down a busy street in broad daylight, he suspects that covert forces are planning to knife him because he knows too much. When church officials stop him from reading a sensitive chapter on a military hit squad, he assumes they are conspiring with the government to kill him.

As alcohol and sex fail to distract him from the looming stack of horror on his desk, the proofreader resorts to an odd solace: he copies bits of testimony from the poor Mayan survivors, whose naive pathos he finds delightful, into a little notebook, which he carries as a charm against danger. “The pigs they are eating him, they are picking over his bones,” he recites to his baffled colleagues at the church. As the days wear on, fear gives way to anger. Having neither the defenses of a native Guatemalan nor the good intentions of a foreign-aid worker, the proofreader has an especially volatile relationship with the villagers whose memories he has been hired to correct. By the time he has fled to the jungle to work through the final pages in solitude, his pity has transformed into an insatiable rage directed not at the military but at the helpless Indians who just stood there and let themselves be massacred:

I returned to the hut of those fucking Indians who would understand the hell that awaited them only when they saw flying through the air the baby I held by the ankles, so I could smash its head of tender flesh against the wood beam.And it was the splattering of palpitating brains that brought me back to my senses: I found myself in the middle of the room, shaking, sweating, a little dizzy….

Such is the tone of this shrill confession, translated with torrential momentum by Katherine Silver, which hovers around every grudge, suspicion, and itch of a man who is more than a little disturbed. When Castellanos Moya traps his reader in the booth with such a raving blowhard (as he did in a previous novella imitating the rants of the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard), he risks driving us mad. The proofreader’s psychosis, fueled at least in part by Guatemala’s dark past, threatens to upstage the country altogether, as his contemptuous and delusional chatter drown out the voices of the dead. But just because the narrator is paranoid doesn’t mean a death squad isn’t out to get him. In some places, Castellanos Moya suggests in the end, you have to let history work you into a frenzy to have a chance at grasping the senselessness of the present.