We drive into the Black Hills, about an hour from Rapid City, South Dakota, where we’d spent the night. All is quiet in the backseat, where my children’s eyes are fixed on a small screen hanging from the car ceiling. As our car climbs toward Mount Rushmore, they are halfway into the extended climax of Hitchcock’s North by Northwest.

Beside me, my wife, Kate, looks out the window. In a mirror, I catch a glimpse of three of my four children absorbed by a spectacle that I can’t see within the car.

But now we have arrived at the entrance to Mount Rushmore National Memorial. I shut off the video system. The kids sigh. They know the rules we are playing by: movies off when we face an especially awesome vista, or arrive at the gate to a national park. It feels wrong to turn off North by Northwest now, however, when we might watch the final twenty minutes in the parking lot. I had tried to plan it so they would already have viewed the great chase scene across the presidents’ faces before we arrived, but I was off by about fifteen minutes.

I punish myself silently for the miscalculation.

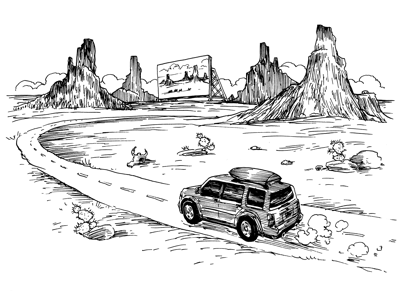

The summer road trip was Kate’s idea, but I was the one who suggested we screen a moving film festival while driving between sights. The road trip, once a rite of passage of young adulthood, is now a rite of passage of middle adulthood, too. Other friends with kids had followed similar itineraries. Our neighbor gave us a folder of pamphlets and printouts of maps from Google. The printouts reminded me of the AAA TripTiks I’d had when I crossed the country twenty years ago. Kate convinced me that we should have hotels reserved and a fixed itinerary, unlike my solo trip, when it was just me, a Honda CR-X, and an improvised route. She proposed that we take our four children, who ranged in age from nine months to just shy of thirteen years old, put them into our Honda Pilot, and drive what would turn out to be four thousand miles in two weeks. Kate convinced me that this was not only the best time to get all our kids into the car for so many miles, but in fact the only time for a long time—maybe the last time—that we might be able to do it.

It had been six years since we’d taken a family road trip. During the second Bush administration we had traveled through North Africa by car with our then three children, tracking down Star Wars shooting locations in Tunisia, and afterward we had driven through much of southern Morocco. That desert trip...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in