Kathy Acker died of cancer on November 30, 1997, the same year that her older contemporaries William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg passed away. At the time, many observed that these three deaths marked the “end of the avant-garde”—or, at least, the end of the avant-garde as it was known in the twentieth century.

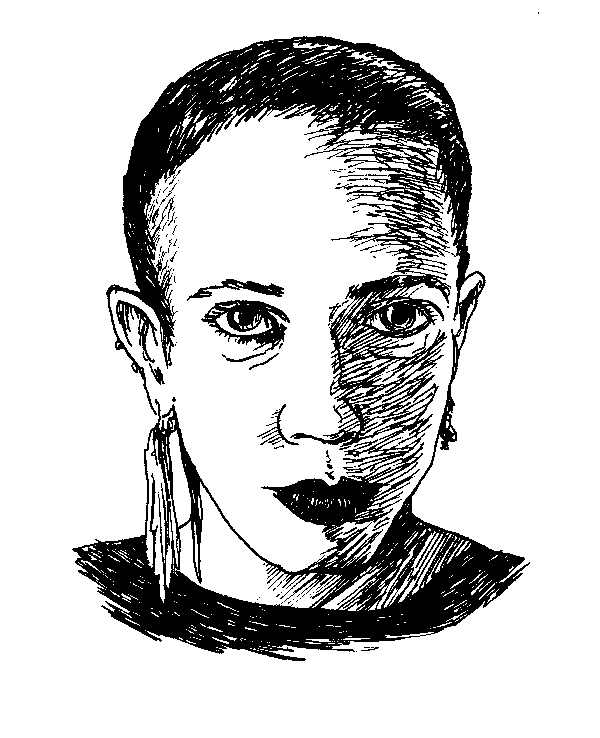

In the years succeeding her death at age fifty, Acker’s work has been the subject of a documentary film, a symposium, and several scholarly works. Attention has mostly been focused on her as an exemplar of the “transgressive” genre of writing, performance, and art popular in the 1980s. Promoting herself more as a rock star than as a writer, she appears in numerous studio portraits taken during that era posed as a precocious child whore in a Victorian boudoir, displaying her extravagant tattoos and bulked-up biceps. Although she’d been actively writing and publishing in the East and West Coast art world and poetry communities since the early 1970s, it was not until the mid-’80s that her work was presented commercially. When her inventive, aggressive bricolage novel Blood and Guts in High School was reissued by Picador in London in 1984, she was hailed as “the high priestess of punk,” an avatar of resistance to the grim resignation of the Bush/Thatcher era. As her image solidified, so did her writing. While the writings that built Acker’s reputation are insouciant samplings of pornography, plagiarized classics, confessional memoir, and political satire, she began taking herself even more seriously than her fans and critics did. From the late ’80s onward, she adopted a somber high-modernist style, identifying herself as a postmodern poète maudit.

While Acker’s work has retained its underground cred during the seventeen years since her death, it’s only recently that her work has been embraced as a powerful influence on a new generation of (mostly female) contemporary writers. Her appropriating compositional style prefigures the oft-debated narrative strategies of writers whose recent novels are littered with emails, transcribed conversations, text messages, found conversations, and diary entries (as if a disjunctive narrative style had never been used before the advent of digital media). In a recent informal survey of Acker’s female contemporaries conducted by Emily Gould and Ruth Curry of Emily Books, an indie e-bookstore, Acker’s name recurs as a primary influence. Her image has faded but her writing remains vivid. This shift makes Semiotext(e)’s publication of Acker’s 1995 email correspondence with media theorist McKenzie Wark extremely well timed.

I’m Very Into You is a collection that includes 103 pages of emails that Acker and Ken Wark exchanged over seventeen days at the dawn of the internet era. Acker met Wark in Sydney during the summer of...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in