Continued from Part One

A SEVENTH WAY: AS NEARLY INFINITELY ABUNDANT

The place is rapidly … sinking into a Blade Runner dystopian futurism…. The air is unbreathable, the water undrinkable, the transit system impenetrable….

—Time Out Los Angeles Guide

(the guide I purchased upon moving here in 1998)

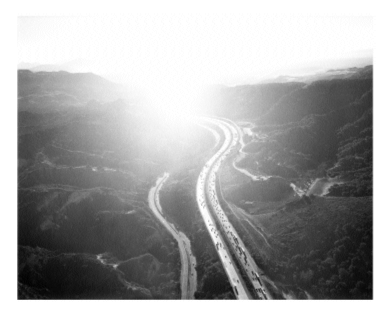

L.A. County spreads out over 4,084 square miles. It is the second largest U.S. metropolis (after New York) by size and population: more people live in the entire four-county greater Los Angeles area than in each of the least populous forty-two states. L.A. ranks as the largest U.S. industrial center and hosts the nation’s busiest port. I live in a world Valhalla for wealth and consumerism. The nearly incomprehensible quantity of people’s connections to nature in L.A. could mobilize a light infantry of nature writers. And all this nature is of such critical importance because these connections—how we use and move and transform nature here—entail enormous consequences for places in the U.S. and throughout the world.

There has been Walden Pond, and there have been John Muir’s Yosemite and Annie Dillard’s Tinker Creek and Barry Lopez’s Arctic. And on the reimagined map of nature writing, there should be Los Angeles—and not just because nature is so wildly abundant here, and what happens to it so globally consequential. L.A. is also the place where the failures of our stories have played out in such exaggerated form, and where the usefulness of really seeing nature is perhaps most urgent. Because L.A. has always enjoyed an especially dramatic relationship to nature, to stories, and above all, to nature stories.

AN EIGHTH WAY: AS EXCEPTIONALLY ICONIC

Since the start of the ’90s… many of us [were left] with the distinct impression that… maybe the Four Horsemen were using the L.A. basin to warm up before riding on to the actual Apocalypse.

—Time Out Los Angeles Guide

Has any city engendered more enthusiastic myth-mongering? In L.A.’s special, unstoppable, even psychotic tradition of storytelling, we’ve tended to state the powerful vision of nature as a place apart, like most grand American tales, in especially dramatic style. After all, who asks, “Is there nature in New York?” or “Is there nature in Chicago?” One might say that New York and Chicago and Pittsburgh have little nature, but L.A., we like to say, has none at all. Not one whit: L.A. has long symbolized all other cities as places where nature is not.

*

Rain… usually [leaves] people stranded atop their vehicles or entombed in sinking homes.

—The National Geographic Traveler: Los Angeles

How have nature writers, alone in literary circles, been able to resist L.A.? It’s actually quite a lot of fun to write about, even if (maybe especially if) you hate it. The glee in the excoriations is as palpable as the rapture in the paeans. New Eden, Paradise Lost, Utopia, Dystopia, City of the Second Chance, the Great Wrong Place. Since the late nineteenth century boosters marketed L.A. as the American Eden, L.A.’s interpreters have tended to declare that the City of Angels (also the City of Fallen Angels) spells the success or failure of the American dream. It’s the land of economic opportunity or class warfare, ethnic diversity or racial hatred, the democracy of homeownership or the evils of suburban sprawl. Whether describing sexual liberation, environmental ruin, or soaring homicide rates, L.A. stories tend to wax dramatic about what happens here to proclaim that life in America has gone fantastically right or wrong. “It is raining in Los Angeles,” the New York Times reported on the first fall rains in 2002: “People are dying on the highways. Planes are falling out of the sky.” Can you imagine such a Times report about the rains in San Diego or Houston? “There’s a certain kind of white, piercing empty light to the Los Angeles sky,” wrote a film reviewer in Entertainment Weekly shortly afterward, “that can make a person want to commit suicide.” And for what other city would the informational guidebooks—not just the fiction, op-eds, news coverage, and academic scholarship, as well as the weather coverage and traffic reports—describe the place as a staging ground for the apocalypse?

*

Near the [Santa Monica] Pier, the potential for getting mugged [is] almost as good as that for getting a tan.

—Fodor’s upclose Los Angeles

The oft cited refrains “American dream” and “American nightmare” can set eyes rolling in Los Angeles itself. In reality, planes do not tumble from the sky and people do not head for their car roofs when it rains here, and you could spend years and a small fortune on sunscreen waiting to be mugged near the Santa Monica pier. L.A. is not inordinately dangerous: this is not a Gotham in dire need of a bat signal. The sprawl city does boast a plethora of great walking neighborhoods. It can be frustrating to live in such a relentlessly iconic city. But proclaiming the meaning of L.A. will not likely fade any day soon as a national pastime. You could say—to borrow a coinage from the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss—that Americans have used L.A. to think.

All of which makes L.A. an ideally resonant place to challenge the established American nature story, which imagines nature in opposition to cities—and we eye-rollers in L.A. have long been calling for new stories with which to imagine this city. If Los Angeles is really a city of nature, then all other cities must be nature, too.

A NINTH WAY: AS A CASUALTY OF A BROADER REFUSAL TO SEE CONNECTIONS

Imagination is all that finally defines L.A.

—Michael Ventura, Los Angeles Times op-ed, 2000

Really? Nothing but imagination? Of course, if the real L.A. doesn’t always match up to the dramatic parables, these stories have tended to exaggerate more than to make things up. As the city with measurably more sprawl, pollution, ethnic diversity, economic inequality, and homicide than most other cities, L.A. has always tended to push all things American—our trends, ideals, and narratives—to the outer edge, and has pushed few things farther than an ideal of personal freedom. I encounter a salute to this ideal approximately weekly: in the weeks before I wrote this, an L.A. architectural historian told the Los Angeles Times that “you have a sense of freedom here that you don’t have anywhere else in the United States,” and a TV reviewer wrote in the New York–based Entertainment Weekly that L.A. is “the land of reinventing yourself, of discovering new possibilities, new realities, new fantasies.” L.A. has shone as the fabled city where you can start over, cut loose from social constraints, and escape your past. As the astute L.A. writer David Ulin remarked in the Times about a commemoration of the 1994 earthquake: “[It is] expected to be the kind of event that doesn’t usually happen in Los Angeles, a conscious effort to link the present to the past.” In the city that so often exaggerates American trends and narratives, you can most clearly watch the association of the American dream with private desire and a willful blindness to connections.

*

You have an inalienable right to make your real life conform to your dream life.

—CityTripping Los Angeles

L.A. is notoriously short on parks and other public spaces. It is a stronghold of the gated neighborhood. L.A. ranks first among U.S. cities for the number of millionaires and forty-first in philanthropy. Forty-first. Here, you can so clearly observe the tendency—magnified in my adopted town but hardly unique to it—to confuse ideals of personal liberty with an ideal of being free to accumulate capital and use it to do whatever you want. You can watch the failure to ballast the quest for individual freedom with other, long-standing American-dream ideals of equality and community. This is the land of Prop. 13 and Prop. 187, where affluent Angelenos want the cheapest labor but no social services for the illegal immigrants who do it; and want the economic as well as cultural benefits of an ethnically and racially diverse city, but don’t want the diversity in their own neighborhoods; and want private canyons and beaches but expect the public to pay for the inevitable fires and mudslides; and want to commute in fabulously fuel-inefficient cars from enormous houses with forty-three-inch TVs and five bathrooms in remote canyons, but object to smog and traffic and pollution and, above all, to living anywhere near the industry and manufacture that bathroom fixtures, SUVs, and forty-three-inch TVs require. The point is that here you can watch the denial so intrinsic to the great American nature story play out as part of the larger desire to benefit from the innumerable ties to people and nature that sustain one’s life in the city, and yet refuse to make good on those connections.

*

L.A. is the city in me, the city I weave together for myself.

—Leo Braudy, Los Angeles Times op-ed, 2002

Of course, this enchantment with freedom is all very beguiling, and for at least some reasons that are less ignoble than admirable. I live on Venice Beach, after all, and in defense of L.A., I love living in a place where you can rollerblade in a thong at the beach (whether male or female) while strumming a guitar. You can order a hot dog topped with pastrami, chili, and American cheese and wrapped in a tortilla. And I love that L.A. is the sort of place where a friend once began a story, “I went to Terry’s house, and there was Terry, and Terry’s baby, and the baby’s doula, and the doula’s chimp in a dress.” I appreciate the greater ethnic integration, diversity of lifestyles, and flourishing of experimental arts. I have found social and career circles to be gratifyingly more porous than in other places I have lived.

*

[L.A.’s]… best feature is… [that] it does not oppress its citizens with a civic identity.

—Robert Lloyd, L.A. Weekly, 2001

But “individual freedom,” like all grand ideals, is perilously malleable and can serve a range of agendas. And the conviction that it should mean you can do whatever the hell you want cannot possibly have found more extreme expression than in the traditional refrain here that L.A. is, in reality, exactly whatever you want it to be. It’s “all imagination,” “the city in me,” and “your dream life.” Even well-respected critics and writers repeat this shibboleth with astonishing frequency. L.A., so this popular L.A. story goes, is not just a place where we’ve liked to tell stories. It is a story. Literally. And it’s your story, no less, your own home movie. And this pushes the ideal of individual liberty well beyond the outer edge. It’s the American dream on a shooting rampage. If one could expressly design a way of seeing a city to bless people who don’t want to be accountable, this would be it: to say a place is yours to design and define authorizes you to deny all your connections to people, nature, and the past. It palpates with that same potent amalgam of yearning and self-indulgence as the American nature story, which seeks salvation in nature Out There but refuses to see how we use and transform nature in the city.

In L.A., you can most clearly watch the established American nature tale plug into a family of sins committed in the name of the American dream.

A TENTH WAY: AS ESPECIALLY DANGEROUS TO LOSE TRACK OF

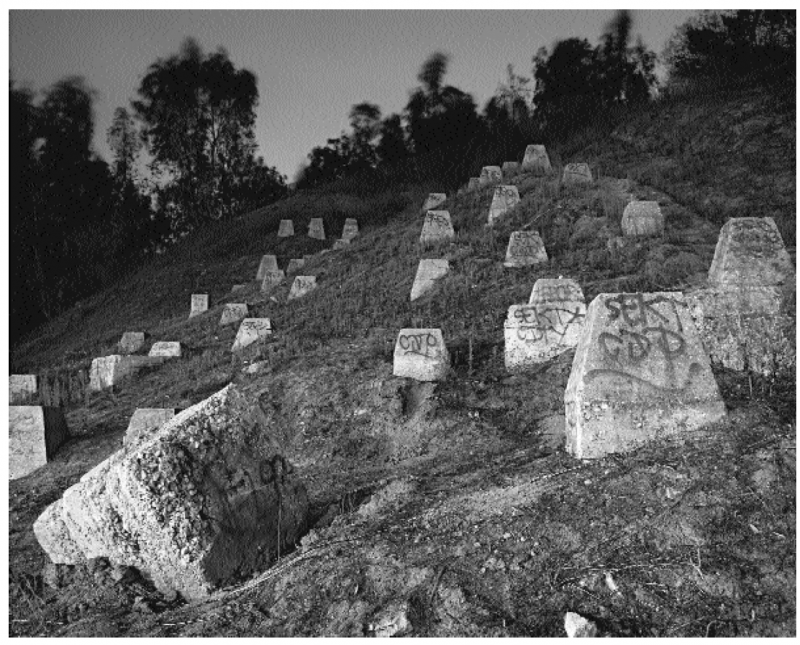

On the other hand, you can also see the consequences so clearly. Whether or not you acknowledge your connections to people and nature, they of course remain operable. Go ahead and ignore your topography, your climate, your hydrology. The air will darken, the mountains will slough mud into your houses, and the lost river will gather toxics and trash. L.A. is not “all imagination.” It has never been “your dream life,” so watch out for the blowback—for smog, mud, freeway gridlock, racial violence, poverty, homelessness, beach erosion, sewage spills, severe water pollution, and the fact that the rest of the West hates you for hoarding their water supplies. Of course, most of these problems will create by far the most havoc for the city’s poorer residents. Wealthy Angelenos, who benefit the most from ignoring our vital connections, also can use their wealth to evade or compensate for the consequences.

This city’s most infamous problems themselves constitute an argument, as large as Los Angeles itself, that our basic stories about nature should refuse to lose track.

AN ELEVENTH WAY: AS A TERRIFIC BOON TO BOULDER AND MISSOULA

None of which is to let Boulder off the hook. In fact, very much the opposite. We may wish away connections in L.A., but we can hardly wish away culpability for the ensuing troubles (and even affluent Angelenos encounter serious daily havoc). Boulder bills itself as the anti-L.A.: it’s the green place, the socially just haven, the great right town. But how much easier is it to keep your air clean when the factories that manufacture your SUVs and Gore-Tex jackets lie in other, distant towns? And you can minimize racial and class confrontations when your own population is white and affluent, while the poor and nonwhite labor force that sustains your city’s material life resides safely far away. Nature writers have documented how cities mine the hinterlands ruthlessly for raw natural resources. But they’ve declined to tell us almost anything about how the largest urban regions, and especially the poorer areas within them, disproportionately shoulder the burden of transforming nature to create all our lovely wondrous stuff.

Boulder couldn’t begin to be the town that Boulder adores without L.A. (and an abundance of other places globally like L.A.)—just as Bel Air and Malibu couldn’t be Bel Air and Malibu in their undeniable glory without their essential connections to the nature and labor throughout L.A. County. Think of a defining difference between Boulder and L.A. as the difference between Malibu and Southeast L.A. but writ nationally. Boulderites benefit proportionately more and suffer far less from how they use nature—which I suspect is one reason why Boulder never claimed my head or heart. L.A. may be a land of troubles, but also gets so unfairly maligned, because being the great right place is much too easy when you don’t have to live with a lot of the problems you create.

Which is oddly heartening, because the City of Angels feels like a distinctly honest place to seek and write about nature. And it’s a thunderously consequential place to do something about the troubles.

A TWELFTH WAY: AS A FOCUS OF GREAT GOOD WORK

And so many people are doing exactly that. The exorbitant social and environmental costs of losing track of nature have consistently confronted this megalopolis with the desperate need to pay attention. As a St. Louis friend who’s an environmental lawyer has said enviously, California generally is “light years ahead of the curve on environmental regulation”—due in no small part to tackling L.A.’s problems. And L.A. itself has emerged in the last decade as a hotbed for the conviction that to make cities more livable and more equitable, we have to move nature through them more equitably and sustainably.

The American city with the worst air pollution enforces the strictest air-quality regulations, which include pioneering emissions standards for vehicles, outdoor appliances, and household products. Southern California also suffers the worst coastal pollution from storm water runoff, with one-third of all beach closures in the U.S. So NRDC, Heal the Bay, and Santa Monica Baykeeper sued the EPA, and in 1999 won a landmark legal victory that, for the first time, requires a metropolitan area to adhere to clean-up schedules mandated by the 1972 Clean Water Act.

Public agencies, environmental nonprofits, and universities have been pioneering strategies to reclaim phased-out industrial lands in the city that’s long held the national title for least park space per capita. In the metropolis that suffers both extreme environmental ruin and polar social and economic inequities, environmental justice activists, including Communities for a Better Environment and Mothers of East L.A., have won nationally recognized battles in the poorer areas of east and south L.A. to shut down polluters. These groups have also waged successful, groundbreaking campaigns to force state and county regulatory agencies to recognize that air pollution and park-space shortages bedevil poorer and nonwhite neighborhoods disproportionately. And there can be no more cutting-edge place to work for urban transformation than on the banks of the country’s most degraded urban river.

L.A. may not be the greenest, cleanest place to be a nature writer, but it is exciting. As L.A. Weekly writer Judith Lewis has put it: “Los Angeles has… [given] me a world to battle as much as I revel in it. It has given me a life in interesting times.”

RIVER TRIP NO. 2

You almost need special glasses to see the L.A. River as the healthy, verdant river that the hundreds of people who are revitalizing it are aiming for. The project will take at least several decades to realize entirely—you also need great reserves of faith and patience—but it will happen if the political will and economic resources continue to flow.

In the mid-1980s, the first calls to revitalize the river, by the artist and writer Lewis MacAdams and his fledgling Friends of the L.A. River, were met with “River? What river?” FoLAR made Willy Wonka’s schemes and hopes for his chocolate factory sound practical. At the time, proposals to paint the concrete blue and to use the channel as a dry-season freeway for trucks received far more serious consideration than FoLAR’s ideas. After a decade of persuasion, their vision would prove to have been superb common sense before its time. And in the last five years, the river’s revival has emerged as a major policy priority, as every imaginably relevant public and private interest—from Heal the Bay, neighborhood associations, and Latino social activists to the mayor’s office, L.A. City Council, and the L.A. County Department of Public Works (our quondam Sun Gods of the river as infrastructure)—has concluded that revitalizing L.A.’s major river will help them ameliorate the city’s worst troubles.

How do you resurrect the river? You have to green the banks. You have to clean the water. And you have to dynamite out some of the concrete. And each of these goals, it turns out, quickly becomes an act of thinking big.

To green the banks, this loose coalition of players has set out to turn the cement scar through the heart of this fragmented, park-starved metropolis into a fifty-one-mile greenway and bikeway, which ideally would serve as the backbone for a countywide greenway network. The Los Angeles River Greenway now consists of two dozen new parks on the ground and many more on paper, and will green and connect many of L.A.’s poorest, and most park-poor, neighborhoods.

To clean up this outsize sewer—which by law (after the NRDC lawsuit) the EPA must now ensure happens by 2013—you can’t just extract the kilotons of pollutants after they enter the river. You have to think about where all the pollutants come from: the weed killers, insecticides, fertilizers, paints, detergents, gasoline, motor oil, car waxes, and countless more toxic everyday products in the basic city-America-2006 street stew that washes into our soil, our water, and eventually our bodies. Alas, the city has spent more time fighting the legal ruling than the pollutants. But to clean the river, L.A. will absolutely have to mandate cleaner industrial processes to manufacture products that are themselves less toxic, more recyclable, more biodegradable.

You have to blow up some of the concrete, if not every last ton: the Seine, after all, runs through Paris in a cement channel. Blast it today, however, and the next heavy winter rains could submerge the Staples Center and Union Station. Rather, before you enjoy the thought of dynamite, you have to dramatically reduce the amount of water that flows down the river during storms. To do that, the river revitalizers propose to divert floodwaters into large basins that can double as parks and wetlands. Even more important, though, they aim to capture as much rain as possible where it falls, rather than rush it into the river to water the Pacific. To do that, Public Works has launched pilot projects to use porous paving, to unpave schoolyards, and to retrofit gutters, freeway medians, and parking lots to pitch water into the ground instead of the storm sewers. You can store the water in underground cisterns and use it on-site—say, to water your lawn—or you can let it drain into the ground and replenish the aquifer (where it’ll clean itself up as minerals in the soil bind up toxic chemicals).

Altogether, restoring the river to health would improve water quality, control flooding, and restore wildlife habitat. Neighborhoods throughout L.A. would acquire much-needed park and green space. It would enhance local water supplies dramatically, and so would potentially change how water moves through the West. All the new greenery would help clean the air. The project has pushed L.A. to the national forefront of urban watershed management. It’s made the river a meeting ground for Angelenos’ broader efforts to enhance the equity and environmental quality of life in Los Angeles. And by reviving a premier symbol of urban destruction, it could make just about anything imaginable in urban transformation. A healthy L.A. River wouldn’t be quite as wondrous as the chocolate factory, but it would be close.

A THIRTEENTH WAY: AS THE FOUNDATION OF L.A. STORIES

This is a happy land for children and all young animals… They live in the pure air and sunshine.

—Health Seekers’ [and] Tourists’… Guide to the… Pacific Coast, 1884

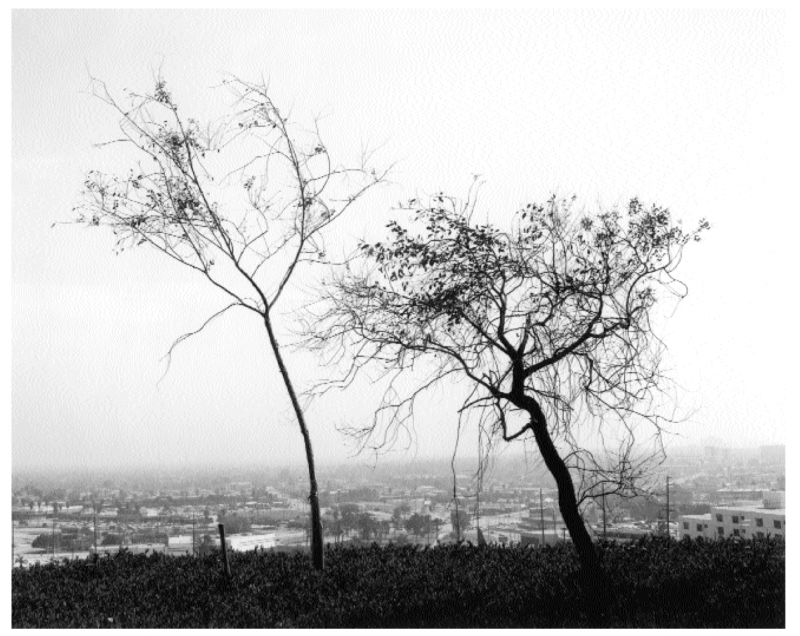

The palm trees were high with scrawny fronds like broken pinwheels… and a droopy ice plant could never quite hold the earth… in place… and an oil derrick [looked] like a rusty praying mantis, trying to suck the last few barrels out of the dying crabgrass.

—Robert Towne, on researching his 1974 Chinatown script

And waiting in the wings are the plague squirrels and killer bees.

—Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear, 1998

The river’s revival, just like its ruin, plays out as every category of nature story. But the stories are beginning to sound better. The wild-things tales are about trying to create healthy rivers and wetlands, and the mango-body-whip tales describe the wise use of basic natural resources. In these social-geography-of-air tales, poorer Angelenos do not get shafted. In the new Zu-Zu tales, we aim to use a wealth of knowledge about the landscape to guide how we transform it.[1]

And the “what it means” tales should be about how we’re imagining nature into the city and our daily lives. Except that we’re not, mostly. Amidst all the new publicity about the river, so many Angelenos still declare that the L.A. River isn’t wild enough to be “natural.” Amidst all the cutting-edge environmental work in this city generally, so many people in and out of L.A. still ask, “Is there nature in L.A.?” Consider, too, that every conceivable brand of environmental advocate, from ecologists and environmentalists to urban planners and landscape architects to policy wonks and politicians and environmental historians, have all been paying a great deal of attention to urban nature—and yet nature writers continue to shun cities as Gomorrahs of iniquitous conspiracies against the natural world (to overstate the case, but only a bit). And as every other literary genre in the last 150 years has exploded with every wild experiment and philosophy imaginable, nature writing alone has remained comparatively unchanged. Unfortunately, the great fantastic American nature story may prove more resistant to any calls to blow it up than the concrete in the L.A. River.

*

To watch the front-page news out of Los Angeles during a Santa Ana is to get very close to what it is about the place.

—Joan Didion, Slouching Toward Bethlehem, 1968

And nowhere has this powerful tale been rooted more tenaciously than in Los Angeles. And here is the last, and perhaps the ultimate, reason that nature writers should flock to L.A. as the logical headquarters to rewrite this tale: L.A., like no other city, has woven this story so thoroughly into stories about the city itself. From the nineteenth-century boosters to the popular Land of Sunshine magazine in the early 1900s to Raymond Chandler and Nathanael West in the 1930s and ’40s to Didion to Mike Davis to the current coverage in the Los Angeles Times and New York Times, L.A.’s interpreters have been obsessed with sea, sun, winds, sky, and palm trees, as well as fire, mud, earthquakes, plague squirrels, and killer bees. And even Davis—from whom I have learned so much about how to see Los Angeles—imagines nature in opposition to cities.

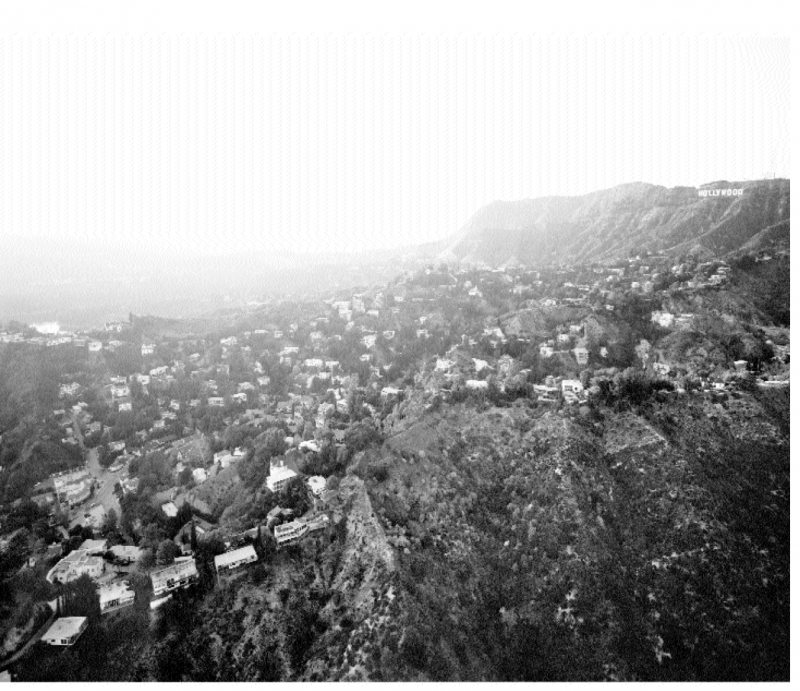

Consider the American dream and nightmare stories. To simplify egregiously, these dominant L.A. narratives really parse into three kinds of tales—dream, nightmare, and apocalypse—that have coexisted since at least the 1930s but have progressed roughly in dominance in that order. In the beginning, L.A. was the American Eden: it was the land of eternal sunshine, healthful sea breezes, and amazingly fertile soils. The late-nineteenth-century boosters lauded the virtues of wild nature to market L.A. as a sort of noncity city. L.A. was supposed to be an Anglo refuge where you could escape the industrial pollution, ethnic and racial conflicts, and financial disappointments in cities to the east—and the ensuing dream stories would continue to use fabulous paeans to sun and sea and air to frame idyllic visions of urban escape, from the post–World War II garden suburbs to today’s canyon living in Malibu and the Hollywood Hills.

And then, the nightmare: the black sky, the fouled sea, the endless pavement, the dying palm trees, the concrete river. By the 1960s, as L.A. defaults on its promises of escape and pushes the problems of American cities to extremes, the Paradise Lost tales invariably invoke the utter destruction of nature to describe a city in which everything has gone wrong. And after the nightmare, the millennium: “Is the City of Angels Going to Hell?” Time asks in a 1993 cover story. In the early 1990s, L.A. reels from the Northridge earthquake, Malibu fires, mudslides, race riots, El Niño, and the O. J. Simpson trial. And the city that destroyed nature and everything else becomes the city where nature roared back for revenge. Apocalypse stories make the opposition of nature to cities decidedly literal.

The history of L.A. storytelling, if more complicated, still basically boils down to a trilogy. Nature blesses L.A. Nature flees L.A. And nature returns armed.

In other words, no wonder I love L.A. This city has been hosting an obsessive conversation about nature for 150 years—or about as far back as when Thoreau camped out on Walden Pond. Nature stories have been more than key L.A. stories. They’ve been the L.A. stories. They’re the driving stories in the city we use to think. It’s ironic, isn’t it? Los Angeles, which symbolizes the city as antinature, really has long flourished as a mecca for thinking and writing about nature, and for telling this powerful story in particular that nature writing has so dedicatedly perpetuated.

Which makes perfect sense, if you think about it. In the modern United States, as in any human society, the stories we tell about nature are the most basic stories we can tell. L.A. has long been a place where we articulate grand American narratives. So it should not surprise us either that the foundational L.A. story is, what?—a nature story—or that we’ve told a wildly evasive nature tale to describe a city that’s pushed the evasion of accountability to people and nature to an extreme. The dream tales have assured us that L.A. is a city of nature where you can escape the social and environmental troubles of cities. The destruction of nature in the nightmare tales—how can you fix something that no longer exists?—laments the city’s troubles while assuring us that we don’t have to do anything because the problems are beyond repair. And how much further past salvation could a city be that awaits imminent millennial annihilation by nature? Here is a city where we’ve dreamt brilliantly of virtue while doing spectacularly unvirtuous things. It practically vibrates with brilliant denial in the service of spectacular yearning, self-interest, and material indulgence. And the city’s definitive story is a way of seeing nature that allows for and encourages these exact evasions.

What we need in L.A., as elsewhere, is a foundational literature that imagines nature not as the opposite of the city but as the basic stuff of modern everyday life. Less apocalypse, more mango body whips. Less maple mojo, more actual maple trees. We could use a great deal less “It is raining in Los Angeles. Planes are falling out of the sky,” and a lot more tales that explore our daily, intertwined connections to nature and to each other—such as “Enjoy the beauty of another culture while learning more about wastewater treatment and reuse.”

I love that L.A. has been a uniquely powerful place to tell American nature stories. But as long as L.A. has been a mecca for American stories, writers have been calling for new stories with which to see the city. And nature stories have to be the logical place to start.

POSTSCRIPT: THE CONFLUENCE

After I found the L.A. River, a year after I moved to L.A., I went searching for the confluence with the Arroyo Seco: the area where L.A. was founded, and the rough center of the river and the L.A. basin watershed. You cannot be surprised to hear that this spot can prove almost impossibly difficult to find. Even in the Thomas Guide, the bible of maps for finding one’s way around Los Angeles, the blue line of the Arroyo peters out about a mile above where the two concrete channels do actually meet.

The day I found the river remains one of my finest days in L.A. I was looking for birds, so I visited three short stretches where the Corps had left a soft riverbed: a flood control basin near the headwaters; an eight-mile piece in the middle, where the water table rises so close to the surface that it would punch through concrete; and the three miles of tidal estuary at the mouth. I started upstream in the San Fernando Valley, on the sole half mile that doesn’t have any concrete at all. I continued downstream to the middle stretch above Downtown, which boasts an inspired new string of pocket parks with native vegetation and outdoor sculptures. Both stretches teemed with herons, ducks, coots, and other birds. Far downstream, in Southeast L.A., the channel widens to the girth of a freeway, and I ended the day looking out over the river from atop a thirty-foot wall. Scores of black-necked stilts picked their way around upturned shopping carts. A mallard shot down the swift current, and swallows sliced the air. The sun set spectacularly to the southwest through power lines, billboards, and the smokestacks of the L.A. Harbor. A man on a horse rode by, wearing a cowboy hat, a Mexican blanket, and a cell phone. “This is L.A.,” I thought. I was steeped so contentedly in the Complex Life. All day I had been marveling, “There’s a river in L.A., a real river, what do you know,” and it seemed, after a year of loving L.A. but not knowing why, and of wanting to write about L.A. but not knowing what, that I was now looking at the place (duck-filled, no less) that held the key to both.

With urban designer and L.A. River aficionado Alan Loomis, I lead informal tours of the river—for friends, and their friends too, who like to think about L.A. and who have heard L.A. has a river and want to see it. We walk around the new parks, but we also insist on a stop at the Confluence, which I located at last on my own third try. We wander among the trash and muck, and skirt the homeless tents, and lean against the massive pylons of the freeway overpasses. Here, we say, lies at once the most hopeless and the most hopeful spot on the L.A. River. The geographic, historic, and ecological center of the river, the Confluence is perhaps the most extreme testament to L.A.’s erasure of nature, community, and the past. This spot is at once the logical nexus for the proposed fifty-one-mile Los Angeles River Greenway. Indeed, the city has broken ground on the first half acre of what should, eventually, become a grand central-city park. Here, we say, is one of the finest places to think about the river, which has to be one of the best places to think about L.A.—and L.A. historically has been one of the most powerful places to tell stories about America. You are standing, we allow, at an American narrative vortex. This spot ideally should be swarming with Angelenos, with writers, with nature writers. And to our delight, the people on the tours say, “What a cool place.” They take a great many photographs—more, usually, than at any other stop—and then we continue downstream to imagine the future of L.A. and the Los Angeles River Greenway at a place where you can drive into the river Downtown.

An earlier form of this essay appeared in Land of Sunshine: An Environmental History of Metropolitan Los Angeles (William Deverell and Greg Hise, eds. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005), used by permission of the publisher.