A fertile fashion breeding ground consists of social pulls and tugs: the need to belong, the need to break free; the urge to disappear, the desire to be seen. In the years following the death of Mao Zedong, when China commenced one of the most extreme fashion transformations in history—from collective, state-produced attire to the label-glamor of global pop-consumerism in less than two generations—these tensions were manifold. “People in reform-era China [1976–89] wanted to be citizens of the world,” writes material-culture historian Antonia Finnane. They also wanted to escape from years of mass identity and become individuals: “There was this deep hunger to do something among youth that would express a little bit of… individual rebellions, self-expression, and to be cool,” says journalist and China scholar Orville Schell, who has been splitting his time between China and the United States since 1975.

The first indications of the consumer culture and brand prominence that exist in China today (the country has been the world’s second-biggest consumer economy since 2013, spending $3.3 trillion in private consumption) can be found in the turmoil, confusion, influences, and uncanny fashions of those reform years. Then, as now, it was the emotional impact of fashion, the charged unsteadiness of the possibility for new identities, that electrified the air.

Let us set the scene as turmoil begins in 1966. Mao is reinvigorating his campaign of permanent revolution, and has called for the purge of all things old-minded (that is, Confucian and feudalistic), as well as anything foreign or bourgeois. Chinese fashion quickly reduces to “three old styles” (lao san zhuang) in “three old colors” (lao san se), but the emotional impact, political implications, and physical repercussions of clothing skyrocket. Contrary to popular Western belief, the iconic square-cut and unisexual uniforms of Chinese communism—the “Mao suit,” the youth jacket, the military coat, all in drab grays and whites and blues, with the occasional, coveted army green—are not outright mandated by the party; rather, they are unwritten and spontaneous responses to anti-bourgeois sentiments, military propaganda, revolutionary fervor, communist ideals, social pressures, and personal beliefs. Clothes can show allegiance or disguise it; they can help the wearer wield power or relinquish it, hold her head high, or avoid getting her nose shoved into the dirt.

The Red Guards, legions of revolutionary students sporting red armbands, take it upon themselves to “destroy the old and establish the new,” the Peking Review (later called the Beijing Review) announces in September of 1966. These youths, with Mao’s blessing, are effectively above the law, and over the next decade the reach of their destruction will know few bounds. They smash villagers’ ancient tablets and burn feudal-era books. They incinerate the visiting Mongolian ambassador’s car. They shut down beauty parlors and cut the clothes off women who wear slim-fitting “bourgeois” pants. One group assaults a young man because he has oiled his hair. Another boards a bus and humiliates anyone wearing “capitalist” leather shoes. They bust into a foreign office and literally grab British diplomats by the balls, forcing them to frog march. In Shanghai, they ransack a businesswoman’s house, shatter her record collection—Mozart, Chopin, Tchaikovsky—and beat her with sticks. If you are accused of being a “capitalist roader” (that is, someone, especially a party official, secretly toeing the capitalist line) on account of, say, failing to wear a Mao pin, they may hang a sign around your neck. They may put a dunce cap on your head and make you repent. Perhaps you will be sent to labor in the countryside. Perhaps you will be shot. A simple jacket that looks too new or is made of expensive cloth can become a fashion faux pas of dire consequence. You will be reported as a rightist or counterrevolutionary by your coworkers, relatives, friends. The safest stance is to be shadowlike, to dress so as to disappear into the masses. That, or get a red armband of your own. The Chinese people are thus trapped in the paradox of an ideology that scorns attentiveness to superficial or materialistic fashions yet requires an acute awareness of appearance.

Jump ahead to July 28, 1976: an earthquake kills an estimated 242,000 comrades in Tangshan, ninety-three miles east of Beijing. The disaster is considered by many to be an omen of dynastic change, and within eight weeks Chairman Mao succumbs to illness and dies, aged eighty-two. Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing, and her tyrannical clique of Mao thought-purists (derogatorily dubbed “the Gang of Four” by the chairman himself) immediately make a power grab, but they are overthrown and jailed by the political bureau and Mao’s chosen successor, Hua Guofeng, with great popular support.

This new Chairman Hua slicks back his hair to look more like Mao and speaks of “the two whatevers,” declaring allegiance to whatever Mao had decided and whatever instructions he had set forth. Meanwhile, Deng Xiaoping, a party leader who was exiled by the Gang of Four in April of ’76, has returned and is beginning to gain influence. Though Deng wears the standard Mao suit, he is more pragmatic than Hua, and he elaborates on Mao-thought, speaking of “seeking truth from facts” and calling for China to integrate theory with practice. “We cannot mechanically apply what Comrade Mao Zedong said about a particular question to another question,” he says on May 24, 1977, while in conversation with two members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Two months later, Deng Xiaoping is reinstated in his role as vice premier. Deng is technically Hua’s subordinate, but his pull in the party and strong ties with the People’s Liberation Army (the PLA, China’s military), developed over his decades-long political and military career, enable him to dominate the national agenda and effectively take the helm. He calls for the Four Modernizations (advancements in agriculture, industry, national defense, and science and technology) to be achieved in conjunction with massive political, economic, and social reforms. Old-fashioned Marxism is no longer relevant: “Engels did not ride on an airplane. Stalin did not wear Dacron,” he says, referring to the polyester that had been used to make breathable summer shirts for privileged comrades since the mid-1960s. High-tech and durable, the fabric has attributes that align with Deng’s vision of what China should become, and after his pronouncement Dacron is elevated to a more conspicuous symbol of status: the emblem of progress. That same month, an opinionated shopkeeper in a rural commune halfway between Hong Kong and Guangzhou observes how peasants have scarcely enough coupons for cheap cotton, let alone anything synthetic. One of the best ways to improve people’s lives, he declares, would be to increase the availability of Dacron.

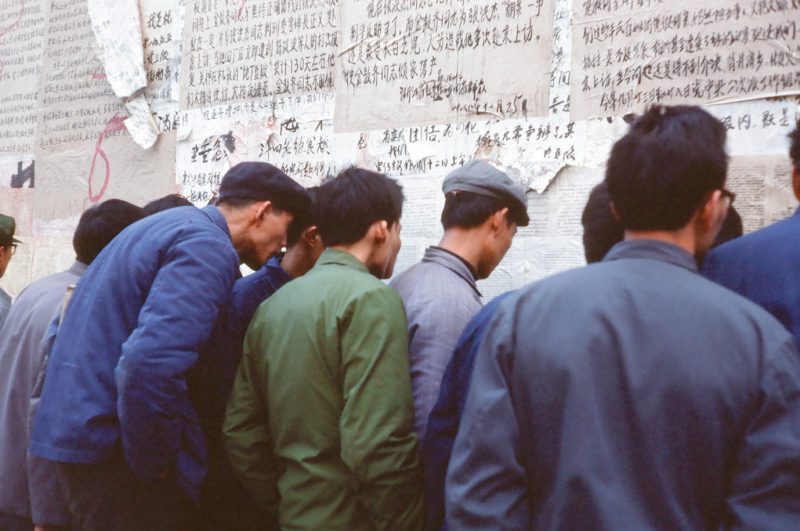

Deng’s first major charge is to decentralize and decollectivize the Chinese economy, starting with the colossal task of breaking up Mao’s agricultural communes. Then he strategically dismantles Mao’s personality cult, reappropriating Mao’s description of Stalin to suggest that, like the fallible Soviet leader, the great chairman was only 70 percent correct. Under Deng’s direction, a new constitution is drafted in March of 1978, which allows for some free-market labor and gives the people “four big rights”: to speak out freely, air views fully, hold great debates, and write “big-character posters” (large, handwritten posters used for protest, propaganda, and mass communication). The public responds by eagerly venting its desires, stories, and grievances on what becomes known as “the Democracy Wall”—thousands of big-character posters tacked up near a bus station in Beijing. These posters tell the stories of individuals tortured by the police, and give peasants’ accounts of hunger and starvation. They call for things like “freedom to travel,” “modernization of lifestyles,” and the need for “learning from other countries.” Similar posters appear on walls throughout the country; Deng calls this “a good thing.”

In December of 1978, at the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), China officially adopts an open-door policy and normalizes relationships with the West. The first experiments with a socialist market economy go into effect, and groundwork is laid to establish special economic zones in various southern coastal cities that will offer labor, land use, and tax incentives that encourage investment by foreign companies producing goods for export. Among the first companies to move in will be textile factories relocating from Hong Kong.

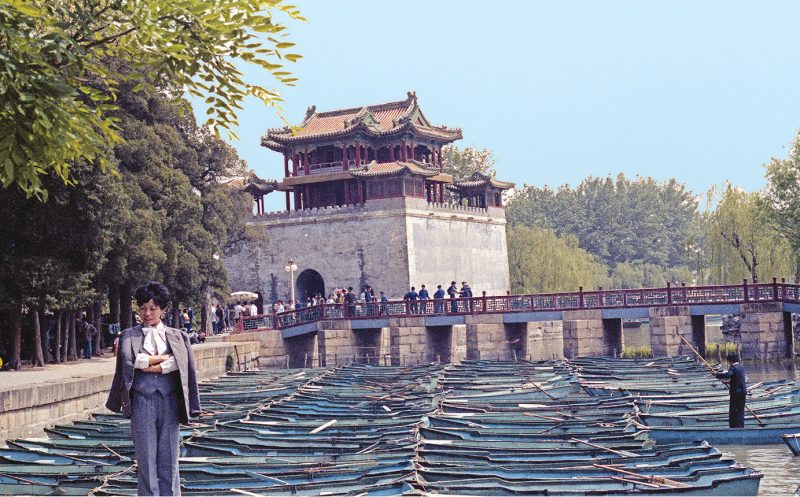

In January of 1979, Deng visits the United States to nurture new relations and learn about US manufacturing techniques. At a rodeo in Houston, the vice premier accepts the gift of a plaid shirt and dons a ten-gallon hat.

A subculture, meanwhile, has begun to emerge. One autumn evening in 1978, Orville Schell, who at this time is the China correspondent for the New Yorker, is hanging out at a seedy Beijing bar called the Peace Café. Wang Zaomin, a young PLA soldier by day and amateur pimp by night, enters the scene dressed like an exquisite corpse: he wears an “English-style trench coat rakishly buckled at the waist, and a crumpled felt fedora,” as Schell describes in his book Watch Out for the Foreign Guests! China Encounters the West. “His upper lip sports a fuzzy moustache not yet ample enough to need trimming… From the chin up he looks like a gangster. From his neck to his knees he seems like an Englishman who has just stepped out of his neighborhood pub into the London fog. But below his knees, where his army pants emerge to meet his khaki sneakers, he looks Chinese.” Compared to his fellow barflies, still in their typical blue jackets and Mao caps, Wang looks “utterly alien.”

Wang Zaomin is what would come to be called a liumang, a deeply connotative and even incriminating classification that is difficult to translate. Sinologist John Minford finds rough equivalents in “hoodlum,” “loafer,” “hobo,” “bum,” or “punk”; essayist Zhou Zouren leans toward “picaroon,” from the Spanish picaro (“rogue”). A literal translation of liumang is “wandering commoner,” one who has lost his physical or spiritual home, and perhaps this interpretation lends the most insight: the liumang of the late ’70s and early ’80s are an emerging culture of “waiting-for-jobs” youths. After the communes are broken up, many citizens who had been sent to work for the revolution in the countryside are abruptly discharged back to cities, where employment is scarce. The liumang are a new generation of delinquents—often the younger brothers and sisters of Red Guards, too young to have fully participated in the Cultural Revolution—coming of age in this unstable clime. They are riffraff and fringe-dwellers, cruising around on Pigeon bikes and 90 cc mini-choppers. They are bored, dismissive, and “blatantly out of step with or in opposition to the normal order and the moral precepts of the society,” as cultural critic Yan Jingming puts it.

The bad boy, Joseph Heller–ish Wang Shuo is a sardonic novelist and screenwriter whose work perhaps embodies the vision of the liumang best. His characters are crass and fast-talking vagabonds who peddle on the black market, make it a principle to have no principles, and mock authority at every turn. “All of the impetus for openness and reform comes from hooligans,” Wang will tell the New York Times in 1993. “Their craziness is what makes society tick.”

Take, for instance, twenty-year-old Hong Ying. In 1982, she doesn’t wear panties under her skirt. She cuts her hair in audacious styles banned in hairdressers’ shops. She wanders from one house party to the next, dancing to disco beats with the lights off, stomping her heels as if to break the floor. “It was almost as if the key to continuing my vagrant lifestyle were dancing up a frenzy until I wore myself out,” she later recalls. Hong Ying is determined to turn her back on her past—the poverty of her youth, the totalitarian demands and indifference of a family and a society that she does not fully understand. One night Hong Ying leaves the dance floor drunk and vomits in the street. She takes a piece of paper from her pocket to wipe her mouth and finds it is a mimeographed poem from an underground magazine: “Before the disaster struck, we all were children, / Only later did we learn how to speak about it.” She feels as if this poem has been written specifically for her, and its power solidifies within her as a passion to use literature to reengage with the world and give a voice to the marginalized in Chinese society. Hong will go on to publish ten novels and many poems, becoming one of China’s most internationally well-known authors.

The bad-boy Wang Shuo, too, will find fame. In the late ’80s and early ’90s, his books become best sellers, and most of his stories and novels are made into films and television series that alienated youths can latch onto or identify with in the post-Mao culture of continual flux. Just as the liumang are a far-reaching group, so, too, is their influence. In the coming decades, many become artists and writers who will inspire new movements and shape the work of subsequent generations, despite frequent censorship. Others become entrepreneurs, among the first to find ingenious ways to profit in the new economy and propel it forward. The liumang may be outliers, but their ideas certainly permeate and spread; they dream and travel and dodge authority, waiting for society to catch up.

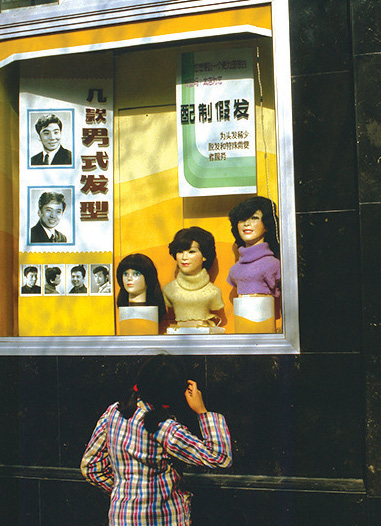

So as China opens its doors to the West, and as Deng is smiling at cowgirl ambassadors in that (in)famous and symbolically potent hat, strange new tribes of liumang are sprouting up from the municipal underbrush. With them comes an array of uncanny and controversial fashions that Schell sees as “indicators of Chinese society in the first stages of a cataclysmic change.” Tough young men teetering in sandals with high heels. Hand-sewn bell-bottoms bearing makeshift labels declaring Levi’s in ballpoint pen. The cast-out tags of imported clothing plucked from the gutter and worn on a string ’round the neck. Color. Patterns. Dacron shirts with floral motifs. Sideburns. Slim mustaches. Jeans. Shag cuts. Perms galore on both women and men. And ubiquitous dark sunglasses with the sticker of their maker still on the lens to show (sometimes falsely) that they were made abroad.

These trends seep in from newly revived contact with relatives in Hong Kong and Taiwan, foreign travelers who attract crowds of onlookers wherever they set foot, and from the thrilling introduction of imported movies and TV. The Japanese film Manhunt, imported in 1978, popularizes the trench coat and long hair. The 1980 TV show Man from Atlantis, an American sci-fi adventure series (and a stateside flop in ’77), stars an aquatic hunk with light-sensitive eyes, making big sunglasses an instant hit. The sunglasses are even nicknamed “Mark sunglasses” (Maike jing) after the lead, Mark Harris (Patrick Duffy)—a play on the term “blind glasses” (mang jing), the primary use for shades before. Also in 1980, bell-bottoms appear on actress Shao Huifang in Spectre, a mainland-made film about a woman fleeing the Gang of Four. Though bell-bottoms became outmoded in the United States about five years earlier, these new-to-China groin-and-thigh-hugging slacks, with their quirky silhouette and a scandalous zipper in front (traditional Chinese zippers were found on the side: on the right for women, the left for men), create an emotional shock that is seized upon by the boldest youths.

State-owned stores steer clear of such novel threads, so many styles are ingeniously and idiosyncratically copied on sewing machines at home or described in detail to daring tailors. What can’t be made domestically is often procured under the table—the special economic zones of Shenzhen and Guangzhou benefit from their proximity to Hong Kong and become key sources of unofficial goods. Indicative of the rise in smuggling is the huge jump in the value of items caught by customs: from RBM 2.27 million in 1978 to over 100 million in 1981. Deng’s foreign-investment initiatives are also taking hold, and thanks to the influx of factories producing goods for export, Zhengcheng township becomes the “blue-jeans capital” of Guangzhou (and eventually the world; by 2010 the river there will be stained indigo from the production of over 200 million denim garments per year). The surplus from these export factories is sold to domestic buyers, then resold alongside secondhand imports and shop-soiled clothes in (often unlicensed) stalls at the street markets that are popping up from nowhere into the new socialist market economy, where entrepreneurial vendors eagerly trade anything, everything.

Hairstyles, the most accessible fashion statements, spread like a fever. As early as 1977, salons with permanent-wave machines open their doors in Shanghai. Li Xiaobin, a photographer famed for his street-fashion images of those years, recalls that before the fall of the Gang of Four, “only an artist with an official letter of certification could have his or her hair permed… the society was thirsty for beautiful things.” Even a conservative schoolteacher in Nanjing gets a perm at her boyfriend’s request—and this is a girl who was known to wear long sleeves well into spring because she was too timid to be the first to change. As women in the West are beginning to wear masculine power-suits, many women in China start to appear in makeup, short skirts, colorful sweaters, floral dresses, and heels. “The sluice gates of fashion… are wide open,” writes China correspondent James P. Sterba in the New York Times in the summer of 1981, “and in the last two months, one of China’s long unanswered questions has been decisively answered: Chinese women have knees.”

During these years, “change in clothing, like in politics, was proceeding at a pace of two steps forward, one back,” writes Antonia Finnane. By the time Deng returns from his nine-day trip to the United States, he no longer considers the Democracy Wall posters unthreatening to his command. If at first he had encouraged the populace to speak out, it was only to let them criticize the Gang of Four, which in turn had bolstered his power—but the posters quickly began to denounce him as well. One asks for The Fifth Modernization—Democracy and criticizes Deng Xiaoping by name. Furthermore, just before Deng’s departure, Fu Yuehua, a woman who claimed she was raped during the Cultural Revolution by a party secretary, had led a demonstration in Tiananmen against hunger and oppression—the first organized protest march in Chinese Communist history. Soon after, a group of unemployed youths storm the gates of the Central Committee, and Deng has no choice but to crack down with a round of arrests. Fu Yuehua is put on trial, and though at first her case is recessed for further investigation due to her candid, even graphic testimony, the judge later dismisses the rape charge and she is jailed for libel and disrupting the public order. Wei Jingsheng, the ex-member of the Red Guard who wrote (and signed) that Fifth Modernization poster and published an underground newspaper called Exploration, is also thrown into jail, along with thirty other Democracy Wall activists.

On September 10, 1980, Deng and the National People’s Congress deal another blow: they officially remove the “four big rights” from the constitution.

But on the southern banks of the Yellow River, in the city of Sanmenxia, an adolescent boy, Liu Yang, steals his father’s military uniform and converts the pants into bell-bottoms by flipping them upside down and sewing in a new crotch. His school forbids long hair on boys and requires straight-legged slacks, yet this sartorial culprit flaunts his homemade “trumpet trousers” and lets his hair grow unchecked. Yang’s liberal mother lauds his tailoring skills and indulges his creative flair, ignoring the provincial city folk who consider his rogue appearance the telltale sign of a huaidan—a bad egg.

It is the summer of 1981. Five hundred miles to the southeast, teenage factory worker Lijia Zhang feels as if the government controls even the heat. (Workers at the rocket factory in Nanjing get the day off if the temperature reaches 40 degrees Celsius, but it miraculously hovers at 39.) Zhang sits under a fan one afternoon listening to a speech by her work unit’s political instructor on what she calls “the colorful trash of capitalism [that] was creeping into China’s gray kingdom.” To Zhang, the speech is like an old grandma’s foot-binding cloth: long and rancid. People are nodding off. “Since the reform and opening up,” the political instructor warns the group, “a handful of young people have become deluded by the prosperity in the West and have begun to worship capitalism. Unable to distinguish between fragrant flowers and poisonous weeds, these young people pick up capitalist trash like ‘trumpet trousers’ and rotten music. We must resolutely defend the ‘four cardinal principles’ of socialism and firmly oppose bourgeois liberalism!”

The political instructor then announces the factory’s new dress code: no high heels. No bright lipstick. No hair hanging past the earlobes of men. And the width of pant legs must measure between fifteen and twenty-two centimeters (not too tight, not too wide). As he speaks, a giant poster behind his head incongruously portrays Karl Marx with wild, bushy hair flowing freely to his shoulders.

Within the PLA, many leaders remain fervent Maoists who are not eager to give up their beliefs. This loyalty to Mao and growing grudge against Deng come to a head in 1981, with the onset of a new propaganda campaign against “bourgeois liberalism” and “the worship of capitalism.” Statements attacking literature, film, clothing, and other aspects of culture are disseminated through PLA-controlled media outlets, supplying anti-bourgeois fodder for ideologues at state-owned factories, such as that political instructor soap-boxing to Lijia Zhang. At first, some independent newspapers refuse to publish the hype, but soon they’re on board, too.

“Is it possible for a young man in long hair and bell-bottoms to save a drowning child?” reporters and gossipers ask. Debate over this scenario becomes widespread. Old-folk vigilantes in cities like Shanghai and Beijing take to the streets with scissors to shred the aberrant slacks, echoing the behavior of the Red Guards some fifteen years before. Little Zhi, Lijia Zhang’s crush, a too-cool coworker at that rocket factory in Nanjing, is nabbed by plainclothes security officers and kicked out of the factory until he chops off his shoulder-length locks. Bell-bottoms and jeans are banned from campuses across the country in the fall of 1981, and the papers try scare tactics to keep youngsters from “aping” Western trends: articles claim the snug fits of Western pants cause chafing, infection, and infertility.

A shift in the structure of the Chinese Communist Party is what boosts the PLA propaganda and in turn pushes newspapers to join in on the criticism. The shift happens at the Sixth Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee of the CCP in June of 1981, when Hua, the ineffective Mao-impersonator, is replaced by Deng’s protégé, Hu Yaobang. Deng meanwhile becomes chairman of the CCP’s Military Affairs Commission, which puts the PLA under his command. Though he gains significant power with these changes, they require serious compromise. In order to win over his critics in the PLA who claim his policies lack ideology, Deng must now adopt a more conservative stance. He begins to side with the PLA in public debates, giving speeches on how liberalism and leftist tendencies must be opposed. He denounces writers and artists who express opinions against the government or appear to be pro-bourgeois, demanding that they self-criticize publicly or else be sentenced to jail like those who wrote on the Democracy Wall. The newspaper China Youth Daily begins to backpedal: it self-criticizes its former views on fashion experimentation and individualism, warning youths to avoid the distraction of frivolous and showy getups when they should be studying and leading the country toward modernization.

In 1982, twenty-three construction workers at the Sixth Construction Company in Shanghai cut their long hair and make headlines as model citizens in the Xinmin Evening News. “We never heard any compliments on our long hair… if one has a bad outward appearance, having a beautiful heart is out of the question,” they tell reporters. That same year, Fashion, a magazine covering foreign style, harshly criticizes the import-obsessed: “There are some girls who are so concerned with being trendy… they imitate Hong Kong girls from head to toe… This kind of adornment breaks away from reality. The new trends sought after by these girls are not the kind of fashionable beauty that belong to our society, nor are they natural or harmonious.”

Reality and practicality, the legacy of Deng’s “seeking truth from facts,” are the refrains of the day, combined with growing undercurrents of cynicism and alienation—the fallout of the repudiation of the Gang of Four and the dissolution of Mao’s demigod status. A public-opinion survey of a factory in Tianjin asks, “What is your ideal?,” eliciting an emblematic response, published in the Tianjin Daily: “I find the revolutionary ideals hollow. Only visible and tangible material benefits are useful.” The ambition and education necessary to achieve material success become prized traits in China’s new free-market socialist economy, and the mainstream epitome of an exemplary civilian is a studious, clean-shaven young man with short hair, a white shirt, and loose pants. Fatefully, this is the exact outfit the Tank Man will wear seven years later, on June 5, 1989, in Tiananmen Square.

Beijing, 1983: a leading hair salon announces it will no longer give men perms. Across town, a woman is barred from entering a municipal office because her long hair is loose instead of pulled back. In a more important municipal building, behind closed doors, the high-ranking CCP officer Zhao Ziyang (who will become the leader of the party in four years) quietly slips out of a Western blazer and back into his Mao jacket.

That year, jean-clad kids with ghetto blasters can be found even in the sticks. But in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan, a hotel employee is sentenced to seven years in prison “for illegally producing ‘obscene’ music tapes” that contain romantic ballads by the permed-haired, painted-lipped, high-heel-wearing Taiwanese pop star Deng Lijun. In Nanjing, a movie star named Chi Zhiqiang is arrested and sentenced to four years in prison for dancing with people “face-to-face,” watching banned movies, and engaging in several one-night stands. In Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi province, an organizer of underground dance parties named Ma Yanqin is accused of sleeping with several of her dance partners and is sentenced to death. The official charges are promiscuity and liumang zui, “hooliganism.”

In the summer of 1983, the Ministry of Public Security launches a brutal yanda, or “strike hard,” campaign, to regain a “balance of awe” over a country with a rising crime rate and a populace it feels is slipping out of its control (a statistical analysis of officially reported criminal cases lists the 1981 crime rate at a thirty-year high, and in 1983 crimes by youths made up 60 percent of all crime). “We can’t allow these criminals to carry on undaunted,” Deng tells his minister of public security, Liu Fizhi. “The ‘Strike Hard’ campaign will strengthen the dictatorship; that’s what dictatorship is. We’ll protect the safety of the majority; that’s what humanitarianism is.”

Deng’s idea is to “round up a big batch of criminals in one fell swoop” in big cities every three years. A directive is released by the Central Party Committee on August 25, 1983, that defines the seven types of people who will become the primary object of the campaign. Topping the list are “‘hooligan’ gang members,” followed by “criminals who fled from place to place.” Practically overnight, thousands upon thousands of so-called “criminals” are jailed and rapidly funneled through a decentralized judicial system, resulting in a conservative estimate of 6,000 executions by the end of the year. Other reports count over 1 million arrests and 24,000 death sentences within six months, and there is mention of a secret Standing Committee document that lists 960,000 executions during the campaigns. Within such a context, a catchall charge like hooliganism is terrifyingly vague.

In October of that year, the related Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign is launched, defining spiritual pollution as “the spreading of various decadent and declining ideologies of the bourgeois and other exploiting classes, and the spreading of sentiments of distrust regarding the cause of socialism and Communism and the leadership of the Communist Party.” The government feels a need to regain control not only over criminals but over intellectuals as well. The campaign starts with an attack on “pornography.” In Fuzhou, it is reported that twenty-seven criminals are executed after watching pornographic video tapes; in Shanghai, a play by Jean-Paul Sartre is shut down; in China Youth, a worker complains that his boss confiscated a book containing a reproduction of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus. This is accompanied by a silencing of literature that brings up unwanted theories of humanism, alienation, modernism, and realism. Poets and other dissidents come under attack, and both the director and the deputy chief of People’s Daily are forced to resign for publishing an article suggesting that Karl Marx’s concept of alienation might not apply only to decadent capitalism but to Chinese socialism as well. The campaign swiftly becomes an excuse for hard-liners “to condemn whatever they do not like,” writes foreign correspondent Christopher S. Wren in the New York Times in December of 1983. The central government bans movies and pop music, and writers are castigated for what Wren labels “unseemly individualism.” At a local level, dress-code signs go up in municipal buildings, women get into trouble for using cosmetics and perming their hair, and youths are attacked for dancing and wearing stylish clothes. The Foreign Broadcast Information Service reports that at the provincial headquarters in the city of Lanzhou, policemen are forced to “read good books and sing revolutionary songs” as an antidote to “wearing mustaches and whiskers, singing unhealthy songs, being undisciplined, and not keeping one’s mind on work.”

Around this time, Lijia Zhang is nominated to be a model worker at the rocket factory in Nanjing, but her name is mysteriously withdrawn because (as she later learns) her work-unit leader thinks her naturally curly hair is permed, and he doesn’t like her flashy coat.

But the sluice gates of fashion will not close.

Yu Qiuyu, a professor at the Shanghai Theatre Academy in the early ’80s, hears a conservative warning: “Imperialism came and called us coolies, now it wants us to wear jeans. From now on it will call us goat boys and horse drivers!” Yu refuses to take the comment lying down. “I was youthfully insolent, and knew too well the deceptive witchcraft of this group of far-leftists,” he writes on his blog over twenty years later. “So I mobilized a group of the youngest professors in Shanghai to wear jeans to resist them.” The protest silences critics, and the group becomes known as “the cowboy professors.”

Liu Yang—that precocious tailor who stole his father’s pants—perms his hair in 1983, dyes it blond, and enrolls in the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. In five years he wins first, second, and third places in the first China Youth Fashion Design contests. Ten years later he’s a star fashion designer who needs policemen to escort him through swarms of fans. His designs range from eccentric, handwoven minidresses that look like wicker baskets to black-silk evening gowns that might be mistaken for pieces by Yves Saint Laurent. He creates ready-to-wear lines full of midriff-baring hoodies and shredded jeans, and debuts an haute-couture blue polyethylene skirt that functions as an aquarium: a live goldfish literally swims in the skirt around the model as she walks.

In 1984, Deng, with the push of Chairman Hu, finally aborts the Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign due to growing concerns about losing foreign investors: a significant number of Chinese officials have been avoiding international deals for fear of being “contaminated” by Western contacts. Meanwhile, two young liumang, now nouveaux riches, happily gulp their beers and drag on cigarettes at a nice restaurant in Beijing. They sport mustaches, plastic sandals, sleeveless undershirts, and matching cream-colored sharkskin pants. Later that year, Chairman Hu officially opens the hatch: he wears a Western suit on domestic TV. By 1985, it is not uncommon to encounter a peasant on a country road, clad in a Western suit and tie, riding a bike loaded with live chickens, ducks, and produce. A few years later, a bearded eighty-year-old in Shanghai will walk into a park to air his songbird. In the bright winter light, he will wear a colorful new ski parka and pre-faded jeans.

The year 1984 marks the end of the first post-Mao fashion cycle of many. The social pulls and tugs will continue for the next ten, twenty, thirty years. Calls for freedoms will rise, be suppressed, and rise again. Look at the photos. Pay attention to the cut of the collars, the color of the lips, the prevalence or absence of jeans, the shifting slogans on T-shirts, on walls, and you might just be able to discern whether the tide is going out or coming in.

Qingdao, 2012. Face-kinis are all the rage on the beach. The following summer, hairy stockings meant to deter perverts are the latest fashion trend. The world has come to expect such novelty and ingenuity from the Chinese. But turn your head a moment to look at that woman carrying not one but two Louis Vuitton bags. “It’s the logo-bots vs. the individuals on the Mainland,” jokes Timothy Parent, a fashion consultant in Shanghai. Some analysts predict that by the end of 2015 Chinese buyers will account for half of global luxury spending, and high-end sales are expected to triple in the next ten years. “Just as the Chinese went to an excess in politics and class struggle during the Cultural Revolution, I think you could say they’ve gone to a similar excess in embracing consumer culture,” says Orville Schell. “It’s complicated, but what was lost in the process of the Cultural Revolution was the ability to completely trust your own judgments and, particularly in regard to valuation, what you could say about aesthetic things… When the Chinese began to emerge out of the uniformity of the Cultural Revolution and into a more global, universal world and tenor, people weren’t quite sure what they should want or aspire to.” Enter the dictatorship of the brand.

And yet…

Those Qingdao face-kinis recently inspired a high-end French photoshoot, and Vogue China has gone from scrounging to find one or two high-quality domestic designers to having trouble editing them down to a choice few. There are innovative young designers, like Beijing-based Dooling Jiang of the conceptual-minded brand Digest, who are taking a step back from the luxury-marketing machine. “At first [customers] might be fooled by the luxury brands,” she told Chinese fashion advocate and designer Erik Bernhardsson. “But after they’ve bought ten pieces, they might discover that there’s no substance, only an image. So they’ll look for something else… I think a new generation is growing up, so I have the confidence to wait for a new kind of system… We [the ’80s generation] all hate the old system.” (The wait, in fact, may not be long: a recent market study reported the first-ever negative trend in China’s luxury spending for 2014 and predicted that changing consumer dynamics will favor less-established brands.)

Dooling doesn’t follow the fashion seasons; she is more interested in creating a new language of design than in mimicking or pushing an idea of luxury that comes from the West. Like the liumang of the late ’70s, Dooling positions herself on the fringe in order to single herself out. But unlike theirs, her experience of the West is not a TV fantasy. She has been there, and has come back.

The aspirational attributes of fashion—fashion as mode of action, as a refusal of stasis, as the statement “look at who I can become”—galvanized those reform years even as they paved the way for the superabundance of Gucci and Louis Vuitton. Looking at similar evolutions of fashion under socialist regimes and in their aftermath—such as denim in the numerous Soviet black markets, which involved vigorous postal traffic, speculative alternate economies, smuggling by diplomats, and chains of complacent customs officers—one wonders if fashion is not, as scholar Djurdja Bartlett has written, paraphrasing Marx, “the spectre that haunts socialism.”

That spectre is perhaps what a young girl, JuanJuan Wu, saw one afternoon by a lake near her parents’ house. She was so stricken by the image that she had to avert her eyes. “I remember how sensational it was to see a woman wearing jeans for the first time. I was amazed by the body lines that showed through,” she says. “Who would dare to wear something like that? We all wore loose-fitting trousers in those days. The first time I looked at her, I distinctly remember blushing—almost as if unexpectedly seeing someone naked in public.” Incapable of looking directly at the woman a second time, yet unable to keep her eyes away, she watched the woman’s reflection rippling in the lake.