At the beginning of “Nightmares,” the penultimate song on the second of Starlito’s three full-length mixtapes from 2012, the twenty-nine-year-old Nashville rapper distortedly intones, “The last three books I read were The Power of Habit, Hop on Pop, and Dream Psychology.” What follows is a claustrophobic detailing of Starlito’s nightmares—an overzealous PO, no “pot to piss in,” stuck on a label full of “extra middlemen”—atop a terrain well summarized by his recent reading list of pop science, Dr. Seuss, and Freud.

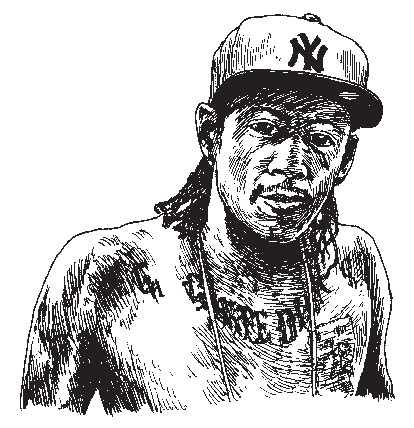

Starlito’s sound has come to be defined by his husky and lithe vocals, embrace of sample-driven soft-rock beats, and complex wordplay. He made a short-lived attempt at traditional commercial success in the middle part of the last decade (while on Cash Money Records, he made a cameo as Lil Wayne’s teammate in Birdman and Wayne’s basketball-based “Pop Bottles” video), and he has spent the past few years self-releasing music and charismatically mapping his psyche on record.

—Joshua Bauchner

THE BELIVER: On “Believe It or Not,” one of the songs featured in your twenty-two-minute music-video suite called For My Foes, you open by saying, “’80s baby approaching thirty / So OCD I might tell you the soap is dirty.” The video ends with you in the bathroom, water running over a pile of bars of soap in the sink: Irish Spring, Lever 2000, Dial.A lot of rap talks about stress, unhappiness, and even depression, but this is at once a pretty explicit and very mundane take on that trope. Why write a song about soap?

STARLITO: “Believe It or Not” is over the Frank Ocean track “We All Try,” and my whole verse was inspired from a line in the original: “I don’t believe my hands are cleanly / Can’t believe that you would let me touch your heart.” I don’t believe; I can’t believe: it’s two different forms of disbelief, which inspired an entire verse about my hands not being clean. I’ll be honest: I was, in a way, just following Frank Ocean’s lead. As I say at the end, “These bars is about soap, / I’m making this all up, / believe it or not.” I don’t think that song actually deals with my mental health issues as much as some of the other music, but in general it’s important to me to portray an honest experience in my music. I think that’s the best art, and the best hip-hop. So that’s part of it—just trying to give it to the listeners straight. Then there’s another part of it that is self-actualization—music as my sanctuary.

BLVR: It’s strange that you say, “I’m making this all up,” because the thing I...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in