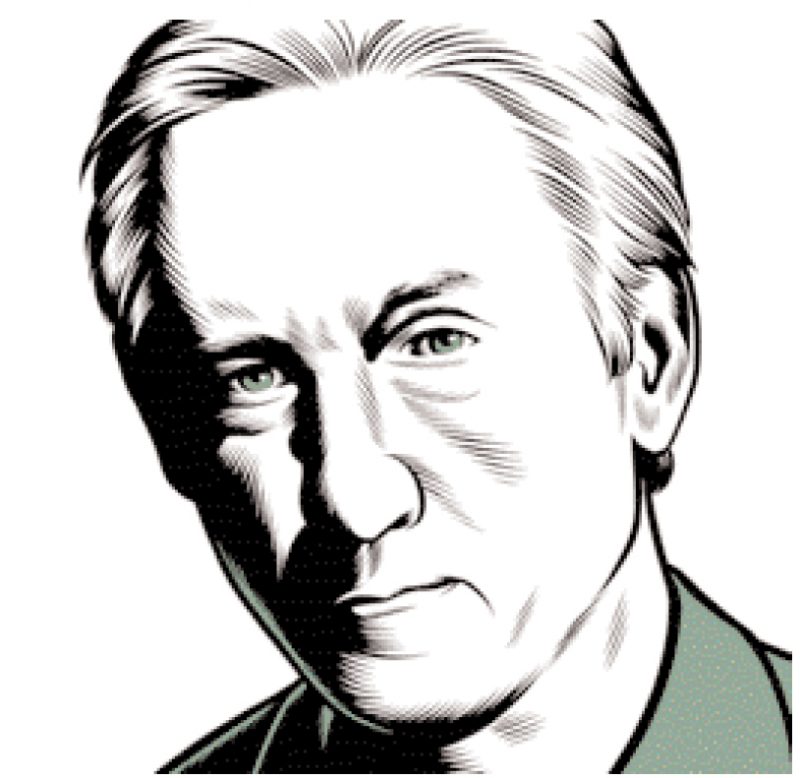

Ed Ruscha is an L.A. artist. In fact, he’s the L.A. artist, although the sixty-eight-year-old has always been resistant to easy labels (“I don’t write those kinds of histories for myself,” he says in a deep, muscular voice that betrays a hint of the Oklahoma lilt of his upbringing). His crucial series of photographic books, where he shot, among other things, twenty-six gasoline stations (remember this number) and every building on Hollywood Boulevard (and repeated this project in 2004) elides the usual photographic sentimentality because the structures are recorded with the cold, detached focus of impassive scientific observation. Ruscha, though, is primarily known for his paintings, which are no less unnerving in their chilly, deceptive straightforwardness. His word paintings—perhaps his most famous works—often turn single nouns, adjectives, or verbs into jarring, confrontational environments set in uneasy color surrounds. What is desire doing written in a milky liquid studded with blueberries (Desire, 1969)? Why is the word dimple, served up in clean, even red letters, suddenly violated by a C-clamp crushing down on the final e (Dimple, 1964)? Why is space written in zooming yellow 3-D block letters, crammed up at the top of the canvas, while a solitary pencil at the bottom is allowed so much legroom (Talk About Space, 1963)? On these canvases, the elementary words fight against all of their multiple meanings—in physical, emotive, connotative, and denotative form. Nearly half a century later, the paintings still hold their disturbing visual-linguistic currency. Ruscha’s lexicon still aggravates (I was gasping for contact swirls over an orange spiral), humors (brave men run in my family is printed against a ship at sea), and mystifies (baby jet letters hover over snowcapped mountains)—because we’re still speaking his language. Most recently, Ruscha has continued work on a series of bare industrial buildings set against swirling acrylic skylines. Perhaps the one thing that connects all of his work is an ongoing interest in the unreal spectacle of public space, which belongs simultaneously to everyone and to no one.

Last November Ruscha met with me on Manhattan’s Upper East Side in the lobby of the Carlyle Hotel, just before a series of paintings he’d created for the Venice Biennale were to make a second appearance at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Ruscha drank tea and talked more about Los Angeles than perhaps he wanted.

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in