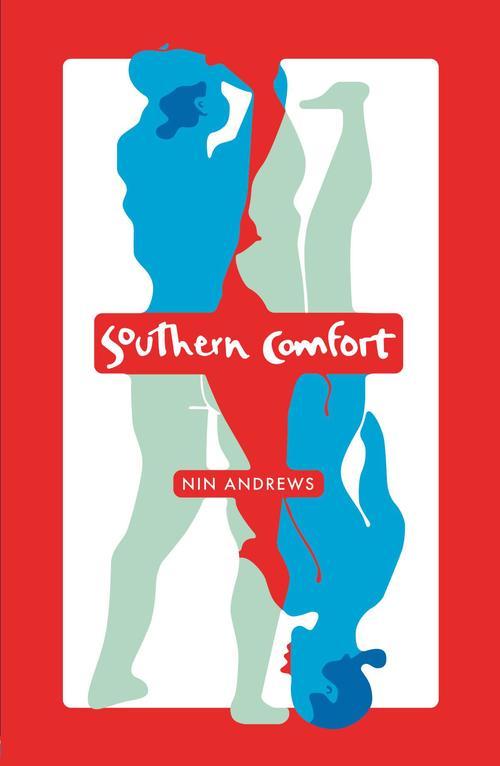

Southern Comfort is, possibly, a collection of poetry about Nin Andrews’s upbringing in the South, or about Andrews’s invented history of a young woman’s memories of her Southern youth, or, perhaps most likely, a mixture of both. The reason the provenance of the poems arises immediately is because the work arrives frequently as prose poems that can affect a reader first as autobiography before they fully register as poetry.

From “After the snake bit him”:

Jimmy liked showing off where the fangs went in. You can’t blame a gal when you grab her from behind, he’d say. Like the snake had to be some kind of gal. I just smirked, tossed my ponytail, and walked away. That was the year I wouldn’t muck the stalls or toss horseshoes or listen to his talk about what he did with this girl or that. Instead I rode my fat-tired bicycle into town and had my hair permed in a thousand curls. All I ever cared about was how I looked….

Born to “a Southern father and a Northern mother,” the dust jacket says, Andrews is a devilish, wily writer who throughout her career has played with the persona she seeks to present to the world, and with readers’ expectations of which of her poems’ anecdotal details are “true.” The woman who writes, in Southern Comfort, “I’m with Elvis so many nights. I can’t help it. I’ve been with him so long. I feel him deep inside me like an ache or pang I can never get rid of ” (“Elvis”) is the same woman who wrote the poem “Dear Confessional Poet” (in 2007’s collection Sleeping with Houdini ), which begins, “How else can I say it? I hate what you do. You and your entire school…” The poet who wrote The Book of Orgasms (2000) and uses a poem such as “The Portable Pussy” as, simultaneously, a cheap tickle and a deep pleasure, frequently presents herself in interviews and photographs as an apple-cheeked, earnest, butter-not-mouth-melting sort. In the recent, uncollected “Learning to Write the MFA Poem,” Andrews suggests she was taught to write “a certain kind of poem,” “these MFA poems / which I despise… because I was taught how to write them / by this asshole professor (he was such a creep) / who was abusive to women, mostly / fucked with their heads if not their bodies, you know the type….”Few current writers are as aware...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in