On the way were still more beers, the night being young in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, and Tim’s blood stanching where the cobra had bitten him. He wanded a good finger over the restaurant’s menu pictures and told me, “If it was you, dude, you’d be dead in this Applebee’s.”

If it was anyone else on this earth, they’d be dead. The African water cobra that had tagged him two hours earlier is so rare a specimen that no antivenom for it currently exists. Yet cobra bite and lagers notwithstanding, Tim looked fresh; he was well on his way to becoming the first documented survivor of that snake’s bite.

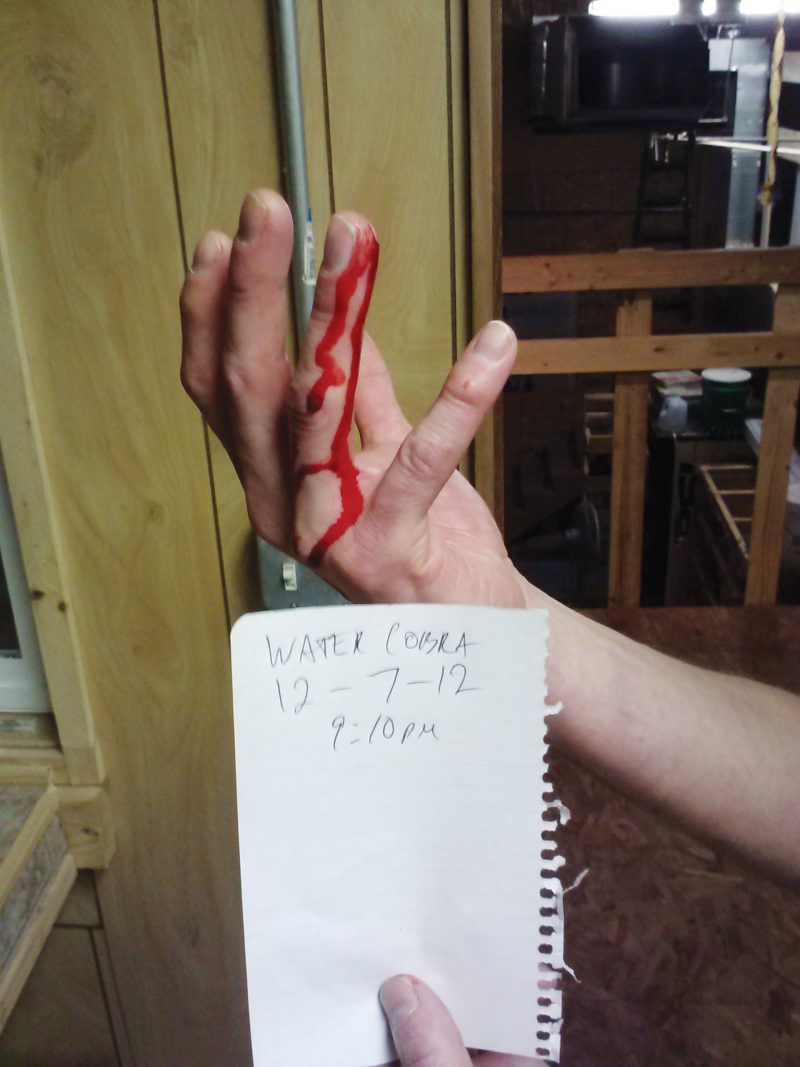

“Which reminds me,” he said from across the table, taking out his phone so I could snap a picture of his bloody hand. “For posterity. After tonight, every book is fucking wrong.”

It was on my account that he had done this, willfully accept the bite. Even though we’d only shaken hands that bright winter afternoon in the salted parking lot of a Days Inn. Tim Friede, the man from the internet who claimed to have made himself immune to the planet’s deadliest serpents. I’d come to test his mettle, to goad him into an unprecedented ordeal: five venomous snakebites in forty-eight hours.

Around us, young people were getting unwound in a hurry. The hour was fast approaching when the restaurant would flip off the apple portion of its lighted sign, clear out the tables and chairs, turn the edited jams to eleven, and allow for boner grinding on the floor space. Our server returned with the beers, and Tim looked up at her with his serous blue eyes, smiling, and said, “You never did card me. You have to guess.” She demurred. He continued: “I could be your dad.”

While Tim fumbled for an in with her, I considered the swollen hand he propped next to his head. Two streams of blood had rilled down and around his wristbone, reading like an open quote. He was a dad’s age, forty-four years old, but he appeared both strangely boyish and grizzled. He had an eager smile of small, square teeth. His hair was a platinum buzz. The skin over his face was bare and very taut; it looked sand-scoured, warm to the touch. Scar tissue and protuberant veins crosshatched his thin forearms, which he now covered by rolling down the sleeves of two dingy long-sleeve T-shirts. His neck was seamed from python teeth.

The snake that had done his twilight envenoming was Naja annulata, about six feet long and as thick as elbow pipe. She was banded in gold and black, a design not unlike that of the Miller Genuine Draft cans we’d bought and then housed on our way to Tim’s makeshift laboratory. When we walked in, the snake was shrugging smoothly along the walls of her four-by-two plastic tank. She was vermiform mercury. And she greeted us with a hiss, a sourceless, sort of circular sizzle, what one would hear if one suddenly found oneself in the center of a hot skillet. Kissing-distance past my reflection in the glass, the cobra induced a nightmare inertia of attraction and revulsion. She had not spirals but eclipses for eyes.

“I love watching death like this,” Tim had said, leaning in, startling me. “Some nights I watch them all night, like fish. Mesmerizing.”

The cobra was one of a $1,500 pair he’d just shipped in, Tim preferring to spend much of what he earns—working the 10 p.m.–to–6 a.m. line shift at Oshkosh Truck—on his snakes. The thing nosed under an overturned Tupperware container while I checked her CV on my phone. Her venom was a touch more potent than arsenic trisulfide. Tim unlatched the front of her tank, reached in, and was perforated before he knew it. The cobra flew at him with her mouth open and body lank, like a harpoon trailing rope.

“Ho ho, that’s just beautiful,” Tim said, withdrawing his hand. There were two broken fangs stapled into his ring finger.

He picked up a beer with his other hand, cracked it expertly with his pointer. I glanced around at all the other caged ampersands—mambas, vipers, rattlesnakes—and I smiled. Rosy constellations of Tim’s blood pipped onto the linoleum, shining brighter than old dead ones.

*

A little while ago, I was searching the web for the man who best embodied the dictum “That which does not kill me makes me stronger.” I was looking for someone who thought he’d succeeded in fortifying his inborn weaknesses, who believed he had bunged the holes left by God. I discovered Tim among the self-immunizers. They’re this community of a couple dozen white, Western males who systematically shoot up increasing doses of exotic venoms so as to inure their immune systems to the effects. Many of these men handle venomous snakes for business or pleasure, so there’s a practical benefit to their regimen. A few prefer instead to work their way from snakes to scorpions to spiders, voiding creatures’ power over them. Most seem to be autodidacts of the sort whose minds recoil at the notion of a limitation deliberately accepted—something I sympathized with, being myself an unfinished, trial creature. On their message boards, Tim talked the biggest medicine.

Their practice of self-immunization has a great old name: mithridatism. It comes from Mithradates VI of Pontus, a.k.a. “the Poison King.” In his lifetime, Mithradates was the last independent monarch to stand against Rome. He tried to unite Hellenic and Black Sea cultures into a neo-Alexandrian empire that could resist the Western one. For a moment, he was successful. Rome was forced to march against and to attempt to occupy the Middle East because of him. The Roman Senate declared him imperial enemy number one. A ruthless general was dispatched to search and destroy. Mithradates went uncaptured, hiding out in the craggy steppes.

Machiavelli deemed him a hero. Racine wrote him a tragedy. A fourteen-year-old Mozart composed an opera about him. A. E. Housman eulogized what was most remarkable about Mithradates:

They put arsenic in his meat

And stared aghast to watch him eat;

They poured strychnine in his cup

And shook to see him drink it up.

Like any despot, Mithradates inverted humanity’s basic psychic task and made insecurity less, not more, tolerable. He trusted no one, and in anticipation of conspiracy and betrayal, he bricked up his body into an impenetrable fortress. Each morning he took a personal cure-all tablet that included things like cinnamon, castor musk from beaver anuses, tannin, garlic, bits of poisonous skinks and salamanders, curdled milk, arsenic, rhubarb from the Volga, toxic honey, Saint-John’s-wort, the poison blood of pontic ducks, opium, and snake venom. His piecemeal inoculation worked so well that, when finally cornered, Mithradates was unable to poison himself. According to Appian’s Roman History, he begged his guard to murder him, saying, “Although I have kept watch and ward against all the poisons that one takes with his food, I have not provided against that domestic poison, always the most dangerous to kings, the treachery of army, children, and friends.”

The official recipe for his mithridatium was lost. But from Nero onward, every Roman emperor ingested a version of the Poison King’s antidote. Some had thirty-six ingredients, others as many as one hundred eighty-four. Charlemagne took it daily, as did Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. The Renaissance poor had their generic versions. Oliver Cromwell found it cleared his skin. London physicians prescribed it until 1786. You could buy it in Rome as recently as 1984. It was believed to kill the helplessness in your constitution. It’s the longest-lived panacea.

*

Tim is adopted. A cop raised him. Asked about his childhood, he offered: “I grew up fighting in the streets of inner-city Milwaukee.” He once tried to reach out to his biological parents after one of his children was born dead, strangled by the umbilical cord. “I thought it might be some kind of genetic thing,” he told me. “But I never found out. I couldn’t get an answer out of them as to why they didn’t want me.”

What he’d wanted for himself was to be a Marine, a Special Forces agent, but he broke his ankle in a car accident two months before basic training. He took a year off, re-enrolled in basic, re-broke the ankle. He could never be Special Forces if he couldn’t jump out of a plane, so he did the next best thing and became a high-rise window washer.

Ten years of window washing put him up to injecting snake venom. “Why?” He explained, “Because when you wake up feeling no pain, then you’ll know you’re dead.” He began by injecting a dilution of one part Egyptian cobra venom and ten thousand parts saline solution into his thigh, every week for a year. Then he upped the potency to one to one hundred, including in the mix Cape and monocled cobra venoms. From his journal of that time:

9-17-02

Small rise in fever, but started to eat and drink. No painkillers yet, but I’m barely hanging on. No one was allowed near me.

9-18 to 9-23-02

To sick to take notes, just don’t care.

9-24-02

This is the first day of puss release, thank God. 3:00 p.m., puss release with great pressure. Urine is clear, no painkillers, no antivenom, no hospital. 6:00 p.m., had second puss release. Couldn’t walk, needed to crawl.

He was left with a six-inch-by-six-inch scar on his leg and an immune system with twice as many venom-specific antibodies as most people have regular ones. He’s since repeated the procedure with mamba and rattlesnake venoms. He takes booster shots every couple of weeks, and he has begun immunizing against the inland taipan, the deadliest terrestrial snake. “There’s no standardized guide to this shit. Everybody’s different.

I sort of wrote the handbook on self-immunization,” Tim said, referring to a self-published PDF available on his website for twelve dollars.

“I’m separated from my wife of fifteen years because of this. I didn’t change oil or cut grass or really be a husband or father. I was researching venom twenty hours a day. I had

a thirteen-hundred-dollar mortgage. One day I came home and my wife had taken the kids, and she had left.” With her, he’s maintained a kind of relationship; it’s his kids, Tim admitted, that he’s lost touch with. “My wife was supportive, but I never needed her. Oh, she’d said, ‘The snakes or me’ before I lost our house. I was sleeping in a tent. My two kids are fifteen and six. But self-immunization is my entire life.”

*

Snake venom is this cocktail of ribonucleases, nucleotides, amino acid oxidases, and so on that, once injected into prey through hollow fangs, immediately goes to work disrupting cellular function. It breaks down tissue proteins, attacks muscles and nerves, dissolves intercellular material, and causes metabolic collapse. The stuff is usually classified as either neurotoxic (if it attacks the nervous system) or hemotoxic (if it goes for blood components), because even though most induce both neuro- and hemotoxic symptoms, each venom tends to induce more of one kind than the other. Meaning, the damage a venom does is species-specific. Snakebite is thus like lovesickness in that each time, you’re wrecked special and anew.

But there are generalities within the two categories. For instance: a potent, primarily neurotoxic venom will effect a quick death. Immediately after the bite, though, comes a lightness of being. Then an acute sense of hearing, almost painfully acute. Chest and stomach cramps next. Sore jaw. Tongue like a bed of needles. Inflamed eyes; lids closing involuntarily. The soles of your feet feel as if they’re on coals. Numb throat. Blurred vision. Then every fiber explodes in pain. From head to toe you are under a barrage of agonizing spasms. Head, neck, eyes, chest, limbs, teeth—searing, aching. The pain feels like a filament burning brightest before it pops. Then your vision splits. Everything splits. Then your muscle contractions are disabled. Your body paralyzes gradually and methodically, as though someone were going from room to room, turning out your lights. Your central nervous system is not able to tell your diaphragm to breathe. You fall down the tiers of a sleep that feels just and due, a reward.

In North America, only a few snakes—corals, elapids, and Mojave rattlers—are neurotoxic like the old-world killers, the cobras and mambas. The vast majority of venomous snakes here—the copperheads, the water moccasins, and the rattlers—are hemotoxic. Though their bites are less likely to kill, their venom, even if survived, often causes chunks of tissue or whole limbs to fall away. It dissolves you. But first you feel a flame bud and lick at the wound. Your skin tickles, pricks, and burns, as if in the process of crisping. Your lymph nodes distend and your neck balloons into a froggish sac. The venom is going from door to cellular door, pillaging. Blood from ruptured vessels escapes into your tissues. Your afflicted limb swells, hemorrhages, and enlarges to monstrosity. You sweat and go dumb. Your blood pressure plummets like a barometer before a storm. You see double, go into shock, and barf up everything. It then feels as if red-hot tongs have plunged inside you, to seek out the root of the pain. This is a living death. You witness yourself becoming a corpse piece by piece. You are barely able to piss, and what does come out is ruby red. You twitch and convulse. Your respiratory system is no longer strong enough to pump the bilge from your lungs. The foam you cough up is pink. And hours to days later, cardinal threads fall from your gums and eyes until, beaten by suffering and anguish, you lose your sense of reality. A chill of death invades your being. Your blood is thin as water. If you die, you die of a bleeding heart.

None of the above, I should say, is Tim susceptible to. He’s been treated with enough neuro- and hemotoxic venoms that his Swiss-army immune system will respond to a single bite by loosing the requisite antibodies to ghost through his blood, disengaging toxins like keys in locks. He’ll swell up, but he’ll be OK—if there’s one bite. It’s multiple bites that might overwhelm him. Still, he’s worked hard to do this: reconcile himself to the old, grand foe.

*

Sifted flurries began to fall on the drive from the restaurant to the place Tim’s rented since separating from his wife. We took my rental car because his rusted-out Intrepid had no heat. Try as we did, we could not figure out how to change the Club Life satellite radio station.

“Here’s one for you,” Tim said, doing an economical frug in his unbelted seat. “Venus and venom come from the same root—love, in Latin. Venenum. Venom used to mean ‘love potion,’ but over time came to mean ‘poison.’”

I skidded us off the highway onto a lightless dirt road. I flipped on the brights and blinked several times to see if there was in fact more past the windshield than unspooling mud and velvet nada. The sputtering heater worked intensely when it worked. The rattle from the backseat meant the diamondback was up.

“Somebody’s getting hot to trot,” Tim said. He’d picked up the snake from a friend around the way. She was going to be the last one to bite him this weekend.

“What I’m saying is—” I began, and then stopped, having forgotten what I was saying.

“Snakes and love,” Tim said. “Love and snakes.”

“You fell in love with these beasts because why?” I asked. “They aren’t pets. A snake doesn’t know what a damn relationship is. The thing doesn’t know your ass from Adam.”

“No, no,” he said. “With snakes it’s cut-and-dried. They’re like, ‘I want to kill you, and you’ll have to survive. I’m a badass motherfucker, and you need to be a bigger badass motherfucker.’ And I’m like, ‘You’re going to kill me every single time, and I love you.’ It’s the best relationship I’ve ever had.”

We jounced past huge barns pushed back from the road. They were hung with one high, bright light, and I felt drawn to each even as I thought of anglerfish and their bioluminescent lures. “But, bro,” I said, “how can you still love them once you’ve become immune to them? You’ve inured yourself to their serpentine wiles. Now what? It’s like—like the difference between being in love and then being in a committed marriage.”

“That’s a good analogy,” Tim said around the Marlboro he was lighting. The diamondback bumped its head along the seams of its plastic Bed Bath & Beyond container. She was not in time with the 4/4 radio beat. “But the snake is ten times the woman for me than the women are. Besides, this shit right here has to be a one-man show. You can’t depend on that snake-woman, because she don’t give a shit. She just wants to eat and shit and kill you in defense.”

Tim told me which unpaved byway to look out for, and we rode on in silence but for the electronica/serpent mashup. With his swollen right hand he handled his cigarette ineptly, inserting and then removing it from his mouth the way an intern might a thermometer.

“But how great is it to be a human and do that? Beat that?” he said, and turned to point into the backseat. “To be one of the only people in history to beat you?” And this is where I did not ask: is it really evil that tempts? Or is the temptation more about thinking you’ve found a shortcut to utopia? I was actually very curious about what Tim would answer. Because, to me, the desire to divinize oneself has always been the most tempting thing in the world.

“Yuh-oh,” Tim said into the backseat.

I heard the rattling afresh, and then Tim muttered something, and then the plastic lid on the case snapped shut.

“The venom,” Tim said, “it gives me something I need. If I had the time and the money, I’d become immune to everything.”

I pulled the car around hay bales and dead tractors and parked next to an unfinished guesthouse on the edge of a llama farm. Somewhere in the night, a windmill lamented oil. We put the beers and the whiskey in the cold-storage shed and went on inside.

A fox pelt and an ankle trap were nailed to the wall of Tim’s foyer. There was no furniture. On the floor in the living room/kitchenette lay a sheetless full-size mattress. Drifts of books on animal tracking and mixed–martial arts. Whey protein and fifteen-pound weights on top of a fridge that didn’t work. A bran of roaches and plaster flakes, all over. Many delicate bones were laid out to dry on paper towels by the sink.

Tim put the rattlesnake case on his mattress. In the light I could see she was gravid with babies. Her poison head tracked me but not Tim as he approached a stereo and cued a skipping CD of Scandinavian heavy metal. We lisped beers and poured Gentleman Jack into them.

I crunched across the floor and picked up an old textbook on venom. I flipped to the middle where there were color photos of hemotoxic snakebite gore: carmine fissures and scabby limbs. Tim walked over, pulled a bookmark from the later pages, and unfolded it. It was a letter addressed to him from the textbook’s author. “Dr. Findlay Russell told me that I’d never be able to survive pure venom,” he said, handing me the letter. Then he told me about antivenom.

Antivenom is no new thing. We’ve produced it for well over a century. Back then, producing it was a simple if crude, painstaking, and resource-intensive process; it remains so today. Take an animal—usually a horse or a sheep because of their blood volume, but a shark works, too—and inject it with small but increasing amounts of milked venom over the course of several months. The animal develops antibodies in its blood. The animal’s blood is then extracted and purified and made into a serum. The serum is injected into a victim of snakebite, and the purified antibodies ride in on hyperimmune plasma like cavalry over a hill. It works similarly to a vaccine, except the immunity it confers is short-lived. The antibodies are on loan, and their introduction doesn’t spur the production of one’s own immune cells.

The problem, Tim continued, is that even with antivenom available throughout much of the world, 125,000 people still manage to die from snakebites every year, most of them in Asia and Africa. This is because antivenom is a very particular drug. It must be stored at a constant temperature not exceeding 46 degrees Fahrenheit. It must be administered by a doctor under controlled conditions. And, in most cases, it must come from the species of snake that did the biting. This all presupposes things like reliable electricity, clean needles, expertise, and the money needed for five to twenty-five vials of antivenom, which in our country cost about fifteen-hundred dollars each.

“The cure is in the snake,” Tim said. “People are stepping on the cure. The cure is in me. And I want to develop a vaccine from it. I want to be the first person in medical history to develop a vaccine with no degree.”

Tim walked into the other room and waved at me with his bitten hand. It looked like a cheap prosthetic, the fingers curled and fused. When I shifted my weight to follow, the diamondback coiled into her S-shaped strike posture, rattling.

This other room was carpeted and clean. Tim had hung it with streamers of shed skin belonging to every snake that ever bit him. Inside a curio cabinet against the far wall were antique snakebite kits, tinned bunk that had never saved one life: chloroform, chlorinated lime, carbolic acid, injections of ammonia and strychnine, tinctures of devil’s dung, potassium permanganate, which was rubbed into sliced-open fang punctures as late as the 1950s. Kits like these were popular especially in Australia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. There they were hawked by traveling showmen who performed sideshow acts with deadly species. These men received so many defensive bites in which only trace amounts of venom were injected that, unbeknownst to them, they built up immunity. They thought they were being saved by the nostrums they’d cooked up in the bush and applied after every bite. They sold them, people bought them, they still died.

Tim showed me a photograph of one such showman, Thomas Wanless. In the photo, he’s crouched in a dirt patch with a tiger snake clamped onto his forearm. Tim’s marginalia read, “NO ONE HAS TALKED TO ME MORE THAN THIS.”

Around us were turrets of books stacked on homemade shelves: God: The Failed Hypothesis, old leatherbound volumes of Darwin, Calculus for the Practical Man, The Immune Self, evolutionary biology, a history of self-experimentation entitled Who Goes First? I pointed out one called The Beginner’s Guide to Winning the Nobel Prize.

He said: “I mean, if I do it, I do it.”

Tim does not have a college degree. He does not have any formal training in medicine. “As much as school could help me, it’s such a crock of fucking shit,” he said. More than anything, he wants a university to agree to study him, to find out exactly what’s going on in his body, how it might be reproduced in an easily injectable form, maybe even underwrite the funding for the vaccine production agreement he has with Aldevron, an antibody research outfit.

But universities don’t and won’t, because of liability issues. They can’t in any way be affiliated with a layman whose only test subject is himself. (When the History Channel asked to feature him on an impressively ridiculous segment a few years ago, his one stipulation—that the network arrange for the University of Wisconsin to study him—was not met.) “If they backed this, and then I died, or I somehow led to other people’s deaths? Well, what’s that gonna cost them?”

Tim won’t personally help anyone who wants to start self-immunizing. “Liability. All you gotta do is make one calculation wrong, and then my shit’s done, too,” he said. What he does to himself isn’t technically illegal. Even the Food and Drug Administration has given him the OK. It’s just that this is not how objective research is supposed to be done.

“Bullshit,” Tim said. “Mice, rats, sheep, equines—but no humans? There’s no other recourse. Only humans know what a thing feels like.

“Whatever, though.” He picked up a framed picture, a former friend who had become the director of a reptile zoo and had gone on something of a smear campaign against self-immunization.1 The glass was webbed from the center out, suggesting a punch. “They may got seventeen degrees, but the one thing they don’t got is their hand in the cage. I just don’t see why they have to cockblock me on this.”

Why would anyone try to stop you? I honestly wondered. “Jealousy. They’re jealous of my ability to not get killed. And they hate me because I’m proving the books wrong. I’m proving them wrong. But that’s the history of self-experimentation and immunology.”2

So, having given up on academia, Tim petitioned the government of Sudan for money. He took out a two- thousand-dollar loan to fly there this coming summer.

“Sudan,” I said.

He told me a Sudanese immigrant he works with on the production line is going to introduce him to the minister of social affairs. Was supposed to have already, actually, when she was visiting Kentucky. But Tim’s coworker’s rental car broke down on the drive from Wisconsin. “Now, instead, I’m going to stay in Sudan for a week, get bit by mambas to buy confidence.”

“That is crazy,” I said.

“This is crazy? You just took a flu shot last week.”

“I’ve actually never had a flu shot.”

“What I have to have is a short nap on a long couch,” Tim said. I went to fix us a couple more boilermakers.

When I returned, Tim took me on a tour of what he called his “peer reviews.” They were printed-out Hotmails from scientists and one Nobel laureate. He’d framed some. Others he’d taped to the wood paneling. They were all polite and vague. “You are probably one of a few people who have immunity against snake venoms”; “I appreciate the studies done on you and there is no criticism.” Each was a printout of the whole screen, not just the text, so there were a lot of perimeter ads for penis-enhancement pills and Wedding Crashers.

“This is as bad as it gets, with a good ending,” Tim said, cheersing with a hand that was rooted with dried blood. Already the swelling was ebbing. “Write this down: if you can’t do it yourself, well, then, what the fuck good are you?”

*

No man has lived through a wider variety of venomous snakebites—if not more bites, period—than Bill Haast. “I’ve been bit more than one hundred seventy times and maybe almost died twenty or twenty-five times,” he said in a 2007 interview, four years before his death, from natural causes.

“I don’t count the little bites.”

In his personal museum, Tim keeps a photo of himself with Haast, the most renowned modern mithridatist. (“I had to fill his gap,” Tim said of the man.) Haast started self-immunizing in 1948, when he injected one part Cape cobra venom and one thousand parts saline solution into his left forearm with a number 25 hypodermic needle. He took a booster every three months and eventually upped his dosage to a drop of raw venom. Then he added Indian and king cobra venoms to the mix. No one could say what might happen to his liver and kidneys. One zoologist wrote to tell him that he wouldn’t “give a plugged nickel” for Haast’s life in three years. But there were no harmful side effects, no severe reactions except for some boils caused by Haast’s refusal to use sterile solutions. By the time he was ninety-five years old, he was injecting himself weekly with a brew of venoms from thirty-two snakes and lizards. “I could become a poster boy for the benefits of venom,” he told the Miami Herald. “If I live to be one hundred, I’ll really make the point.” He lived to be one hundred.

After stints as an engine tester, a bootlegger, and a cashier in a prohibition chophouse, Haast operated the Miami Serpentarium from 1946 to 1984. There, he charged the curious to watch him milk venom from cobras, kraits, rattlesnakes, all of the dread host. He didn’t have a high-school diploma, but he donned a white lab coat when doing extractions. Using no protective equipment, he handled up to a hundred snakes every day of the week. On Sundays he’d release a fourteen-foot king cobra onto the front lawn and spar with it, feint and duck its strikes until he’d grabbed its head and subdued it. (It often bolted for the audience, there not being any issues of liability in those salad days, and he’d have to yank it back to him by its fist-thick tail.)

The Serpentarium was the culmination of a boyhood dream: to encourage venom research by making it easy for scientists, especially those in the United States, to obtain all sorts of snake venoms from a reliable and knowledgeable source. “This venom has got to be useful,” Haast said to his tearful second wife after he was laid up in the hospital by another bite. “It can’t affect every nerve in the body like this and not be useful. It must be. Someday, someone will find a use for it.”

Haast tried. He was leading a promising study on the effects of neurotoxic venom on polio when Jonas Salk discovered a vaccine. In the ’70s, Haast and a Miami physician were using a venom-based serum called PROven to treat more than six thousand people suffering from multiple sclerosis, when the FDA shut them down, citing improper testing.

Scientists and academics did not much love him. “It is hard to evaluate the significance of Haast’s work because so little has been published,” wrote one of his customers, a leading venom researcher. “He has certainly demonstrated that a human being can recover from a hell of a lot of snakebites.” But the self-immunizers Haast begot cherish his work, most of all his long-out-of-print biography. (Tim referred to it as “my Bible.”) In it, Haast is described as “a sometimes unapproachable and stubborn man” who “doesn’t waste motions or time,” who “hopes and plans for the best but expects the worst and is ready to accept it.” He was “strongly individualistic with an almost innate sense of pride. He could never bring himself to ask anybody for anything, least of all to beg or plead.”

Haast was made an honorary citizen of Venezuela after he flew deep into its jungle and saved a snakebitten boy’s life with a transfused pint of his hyperimmune blood. In all, he donated blood to twenty-one victims of snakebite; all of them survived. A letter from one, the director of the Des Moines zoo, read, “Each morning when the sun comes up, I think of you.”

He ate meat on even-numbered days and seldom consumed refined sugar. He was fit and nimble till the end, and unusually youthful-looking. He claimed never to have been sick a day in his life, to have known neither the flu nor the common cold. He didn’t even take aspirin. And he lives on as the self-immunizers’ alpha, the apotheosis of how a man wins hard liberty and authors his destiny.

Haast’s own hands, though, were gnarly. An eastern diamondback bite curled his left hand into a claw. A Malaysian pit viper ossified his right index finger. A cottonmouth bit the tip of his pinkie, which then turned black, lost feeling, and had to be clipped off the bone by his third wife, Nancy, who used rose pruners to do so. Nancy is writing Haast’s updated biography, his first wife having left him before the Serpentarium opened, and his second having departed, saying, “I can’t stand it. I can’t stand it. I love you, Bill. I love you. But I can’t stand it anymore.”

*

It wasn’t a full-blown hangover I had, more like a subcutaneous chafe. I could feel another sour me ruffling against seams that would’ve split had there been one more drink last night. By noon I was on my way back to Tim’s lab.

What little snow there was had stuck, the day swaddled in clouds. The lab was in the old industrial rind along the south shore of Lake Winnebago, in a disintegrating crematorium. Tim was waiting for me amid piles of rubble outside. He had on the same dirty shirts and loose jeans. An open Pabst was in his hand. He introduced me to his best friend, Corey, who works with him at Oshkosh Truck. Corey is brown-haired and haunted. His wide-set eyes seem clear on their surface but marred below, like resurfaced ice, and he wore both a black T-shirt and a trapezoidal mustache. He handed me a beer.

Inside, half a million dollars’ worth of crossbred reticulated pythons spooled in rows and rows of tanks. They belonged to Tim’s friend Gavin, who runs a tattoo parlor while mongrelizing new colors and patterns of snake on the side. Their bodies were taffied muscle, and they moved slowly if at all. The musk in here was hearthy, like wood chips and spoor; sedative, until one got wind of the antiseptic tang of chemicals used to clean up after a thousand digestive systems turning hard-to-swallow prey into boneless shit. This was where Tim slept after his wife left him.

We went upstairs. Under low pipes and cobwebs were many old sofas, and two plastic tubs with an alligator in each. “These were a gift to Gavin, from this guy, before he went to prison,” Tim said. I asked what was going to happen when they outgrew the tubs. He pointed to a picket coop of unsound construction.

In the opposite corner, a doughy man in Sunday shoes was using both hands to rustle sheets of dead skin off a beaded lizard. Tim led us on past, and we entered the lab proper, a climate-controlled shed with room enough for eight tanks. Tim pays Gavin three thousand dollars a year in rent; cheap, compared to the five thousand he spends on the rats stacked everywhere in plastic drawers.

The lizard man’s wife clutched a baby to her breast and followed us in. When she crossed the threshold, the newly interned western diamondback roused herself, admonishing, and the wife decided to watch from the other side of the shack’s one window.

Then a guy named Dan arrived with Tim’s Mojave rattlesnake. The Mojave was smallish and decorated with tan chevrons. Here now, the most dangerous species on the North American continent.3 This Dan placed on the floor, to kneel and poke at with a boldness I thought unwarranted.

Dan resembled nothing so much as a debased tax accountant. Five-five, wire-frame glasses, a dome Bic’d clean, but no front teeth. He regularly fed quarter-sized plugs of Skoal through the slot in his mouth. “She’s a sweetie,” he said, swimming his finger in front of the rattlesnake’s furrowed brow. She lifted her front third off the ground. “She’ll sit on the hook juuuust fine.” Tim was crouching behind the Mojave, talking to me, when she turned and struck at his thigh. “Got only denim,” Tim assured us.

Dan went to get everybody more drinks. Tim decided to take out the pregnant diamondback and practice with a new set of snake grippers ordered specially from Georgia. When he unlatched the box, the snake flowed straight up and out, a djinn from its lamp. She was ornery. On the linoleum, she seemed almost overwhelmed by the forest of legs she could snatch at. Tim tried one of the bigger grippers, speared her behind the head, but the diamondback wormed easily out from under it. She writhed and lunged about like a downed but sentient power line. Using a smaller gauge, Tim pegged her, picked her up, and held her out to us spectators as she yawned, her pink gullet bracketed by fangs that winked drops of venom. Everyone in that room was, deep down, an introverted misanthrope who had never quite lost his adolescent fascination with the death act, snake on rat, who maybe still gazed upon it with a sort of jealousy.

Dan returned with an armload of Steel Reserves and another woman. “I asked you if there was gonna be pussy,” he said to Tim. “All I found…was this.” Her name was Megan. She was a slim woman with a bulb nose and inky hair kept bundled in a red kerchief. Lacy with tattoos, she exuded a pheromonal benevolence. She was Corey’s fiancée, and the night janitor at Oshkosh Truck. But before that, when she was jobless and adrift, Tim had loaned her money, provided her with a place to stay, and put her in charge of his rats. His wife once briefly kicked him out after she found Megan’s colors mixed in with his in the wash.

During quiet moments the night before, he had brought Megan up. “Do I want to see her and hug her and kiss her?” he’d asked at the Applebee’s, apropos of a text message from her. “Of course I do! Do I want her to hold my hand and support me? Yes!” But he waved it all away and explained that love had been the downfall of his immunizer heroes. His mentor “fell off and got foggy” because of a woman. Bill Haast burned through two wives before he found someone who accepted her role in his ecosystem. “Megan knows that tremendously well,” he’d said. “As far as what I need or don’t need.” What he didn’t need was a woman worrying about him, about the risks he accepted voluntarily, begging him to stop. That it might be her who is consigned to the anguish he’s inoculated against had not crossed Tim’s mind. “I’m not some vulnerable idiot,” he went on.

“I know what I’m doing. Meg is horribly special. But I guess what it comes down to is I have to cut a few people out of my life to save a million.”

He slid open the water cobra tank. He withdrew both snakes without incident. They entwined around his right hand in a Gordian knot, and he said to Dan, “There are always girls here.” He propped his smartphone on the windowsill to record a video of the bite. One cobra, having recently shed, looked like she was mailed in good green glass. Tim put her back. He wanted a heavily venomous bite, and snakes are more temperamental when they’re shedding.

The other one was skin-shabby. Tim gripped it by its neck and rubbed it around his left arm, trying to encourage a bite. It remained flaccid and pliant as he brushed it first down and then back up, muttering, “Come on,” apologizing that “it’s not usually like this, I swear.” This was practice for his trip to Sudan, where he’d have to stand and deliver in front of strangers. He pushed the rope of the snake for two more minutes before dropping it to his side and sighing. “Performance anxiety.”

It would have to be the black mamba, then. We took a beery recess while Tim mentally prepped. The black mamba is the snake, according to him. The fastest on the planet. Terrifically aggressive. Unwelcome in zoos. Well over ten feet long, and the gray green of guns, B-52s, all your finer life-taking instruments. The “black” comes from its mouth, which it opens when threatening, and which isn’t pink but obsidian. Without antivenom, the mortality rate of a “wet” black bite is absolute. Two drops—that’s all it takes.

“Let’s, ah, let’s just see,” Tim said, badly missing the garbage can with his tossed empty. He watched as I started then stopped taking this down in my spiral ledger. I looked at him expectantly. “Brotherman, there’s no black mamba on earth with venom enough to kill me.” He made an expansive gesture with a new beer in hand. He embraced my spotlight. “I control them,” he said. “I control death.”

A freight train trundled across the far bank of windows, and the sun didn’t set so much as slowly back away. Tim drank his beer to foam and said, “We go.” He slipped his hands inside welding gloves. He opened the tank and hooked the mamba. He threw down one and then the other glove before taking the snake behind her head. She vined herself up his other arm, tonguing his ardor. She unhinged her abysmal mouth. “She’s opened up!” somebody went.

I thought I could hear a faint but continuous B flat.

Tim held his palm away from his hip as though reaching for another’s hand. The mamba’s gorgon eyes shined with an intense bigotry of purpose. Her exhalations seemed to jelly the air. Tim pursed his lips, tensed, and lowered the open mouth to his forearm. Then the snake nipped him. She nipped him twice, in quick succession, fangs through skin making the same small popping noises as air holes forked in microwave-safe shrink-wrap. Tim’s arm immediately petrified.

“That might’ve been the worst one ever,” he said, carefully unwinding the mamba and dropping her into her tank. He noted the bites on a Sports Illustrated bikini calendar and had me take a picture of them. People cleared out of the lab. He watched Megan go feed the rats through the shed’s window.

“I’ll never be that lucky,” he said to Corey.

“Man, shut the fuck up,” Corey responded. He talked thickly, as though there were a hand around his throat. “You ain’t even divorced yet.”

Six inches away from Tim, at eye level, a monocled cobra hammered the door of its tank, again and again, wishing to interject. “What I’m going to do is go for married chicks,” he said, rotating his forearm, which was now a bloody delta.

“Oh, at Oshkosh Truck, it’s mad easy,” Corey said. “I’ve already had a couple.”

Tim leaned forward and jabbed at Corey with his bitten arm. “Ay,” he said, fixing his eyes. His smile unfastened his face, and for just one instant he looked ancient. “When you getting married, dog?”

They both forced laughter. “If it was gonna happen with you, it would’ve happened a long time ago,” Corey said.

Tim’s false laugh pushed Corey’s out of the room. Dan came back in, accidentally defusing the situation. He was exponentially drunker, with a giant lizard held to one shoulder. He petted it and said in mommy talk, “He’s just a big baaayyy-bee,” whereupon the beast lifted its tail and sprayed a rich fecal foam across the laboratory floor.

“How about that Mojave?” I en-ticed. Tim was by then checking his Facebook messages on his phone. “Hey, should I bring the wife over?” he wanted to know. From downstairs Megan shouted, “Noooooo! She fuckin’ hates me!” She ran up into the lab, a tottering smile on her face, and reminded Tim to take a picture of the swelling that was pushing past his elbow.

“Nah,” Tim said, eyes on his phone. “The wife isn’t coming over, because she says she’s baking. Bitch’s baking? Bitch, you don’t bake.”

Megan sidled up to review the photo, her birdy hand alighting on his shoulder blade. She stepped on Tim’s foot not accidentally but as though flooring him.

“Nine-by-nine-inch swelling,”Tim said. “Now I just need a penis bite. A solid nine all around.” He didn’t betray the awful pain he was feeling, his nerves vised tighter and tighter by his own expanding self.

A little later, good and drunk and sitting Indian-style, we watched the uncaged Mojave thread itself into a spring of stored energy, the position of last resort. Tim did some sleight of hand and collared it. “No dinner and a movie necessary with this one,” he said, and plugged the Mojave into his forearm. It rattled excitedly as it drained itself. Tim’s face gaped into an ecstatic rictus.

When he pulled the snake off, tartarous venom mizzled onto me. “There’s the money shot,” Dan went. This was Tim’s fourth deadly snakebite in twenty-four hours’ time. I scrawled, “To sin is to cheat with order.” Tim saw me writing and said through a grimace, “All right, hold on now, we still got the diamondback tomorrow.”

After that, things got convivial, if hazy. Beers were drunk at a ferocious pace. A gun was brought out, maybe? Tim and Megan went off in the dark somewhere. With the winking meekness of a moonlighting vigilante, Dan explained how he forewent his usual rules and restrictions when selling cobras to undesirables. I poured up large-bore whiskey shots and rather hoped for pandemonium. When the couple returned, it was agreed that the afterparty would move to Tim’s place.

*

I stopped at a gas station to get us some Millers and Tombstone frozen pizzas. When I finally blundered into Tim’s farmland shanty, I found him supine on his mattress with his inflated arms in the air. His wrists zagged at right angles, and his hands hung plump. He looked as though he’d been long planted with his own wilted grave posies. Only Corey and Megan remained; they stood against the wall, looking down at him.

“Who else is impressed by this swell?” Tim asked, a lit cigarette balancing on his lower lip. His face barely chinned above his engorged neck. He was not able to turn to anyone. The holes in him had been squeezed shut.

“This is the sickest I’ve ever seen him,” Megan said.

“That’s what she said,” Tim quipped in response to his own question. Megan asked him to take off his shirts before he swelled up too much. I put a pizza in the oven. Corey’s face contracted into a pitying squinch. What was he going to do, call 911 and tell the Fond du Lac paramedics to bring three kinds of foreign antivenom?

“Shit’s too soft,” Tim said when I brought a slice to his mouth. After swallowing, he went, “There’s room enough for you on here, sailor,” and pointed to the other side of the mattress with his eyes. My face went blank. “I suppose you’re too good for the floor, too?” he asked.

Corey excused himself, saying that, after all, he’s got three kids and a Packers game tomorrow. Megan threw a blanket over Tim, who looked to me. The swelling was creeping still farther, and the blue in his wet eyes seemed unnaturally bright. I slipped into my coat.

You can love a snake, but the snake’s got no way of showing it loves you back. Selective pressures have made it so; the creature lacks the faculties. It probably never had them to begin with. Lucky thing, its existence was never a problem it had to solve—whereas a man like Tim was born a freak of nature, being within it and yet transcending it. He was tasked with finding principles of action and decision-making to replace the principles of instincts. He had to develop a frame of orientation that granted him both a consistent picture of the universe and a basis for consistent living. Thus did he choose to build himself up: his creation is one that does not care and will never cease. Seen this way, self-immunization not only makes sense, it’s the only logical response to his world.

“I am gloved in fire,” he said.

Last one out, I flicked off the light and took the beers with me.

*

The next day came and went. I sent Tim a couple of texts from my hotel room while four inches of snow fell. I wanted to see a fifth bite. When he didn’t respond, I began to consider the attendant legal problems. It’d all been his idea, I argued, freely chosen. I was just there, observing.

Late in the evening, I stopped by. I found Tim huddled over a portable electric heater, only the one light on. Inflamed under his same clothes, he appeared soft but also rigid, like something that had been stuffed and mounted. He’d been lying in bed since I left. “Just staring at the ceiling,” he said. “I came close to crying, and there were a couple uncool moments when my eyes started closing on their own.”

“Do you think you could still pull it off?” I asked.

“If I didn’t have to work tomorrow. Or if you thought you could throw some money my way.”

I patted myself down, shrugged, and said that was against the rules. Tim’s right arm had been cocked Napoleonically, but now he absentmindedly pumped it with his other hand, loosening his elbow. “What you have to understand,” he said, “is you have to become the snake. The snake—they call it a ‘recessive’ step when you lose something through evolution. But the snake improved itself by getting rid of legs, extra lungs, everything.”

He asked me to pass him the fifth of Jack Daniel’s hidden among the bottles of generic painkillers on his countertop. He unscrewed the cap using only his palm. “Had you ever even seen a venomous snake before this?”

I had. One Christmas morning, in an overgrown strip of backyard. I was stalking trash, shooting it with the compressed-air rifle I’d just unwrapped. I stepped softly through rusted bike frames and skirted the Braille of hamster graves. I was about to set sights on a bleach bottle when my body froze. That’s a cliché, but it’s absolutely true: I was arrested by the cold and tingling sensation of the familiar gone strange. I suddenly knew I was in the presence of a ghost.

Amid the litter at my feet was the candy tilde of a coral snake. How long had it been there? Was it offering to bite me? I considered what that might be like, getting digested from the inside out by a creature that could never comprehend in me a full human being. I felt the urge to put my life in its hands, to see just what the outcome would be. I bent to the snake in the grass.

I had no doubt that Tim would take a fifth bite if I coaxed him. But there’d be time enough for that. After all, Tim’s been doing this here, alone, for quite a while, and he’ll be doing it for a long time to come. “To sound arrogant—and I hate to say it—but I don’t think anyone’ll ever be able to go through what I go through,” he said. “Or want to. Not in a million years.”

I looked down and ruffled through the ink-bloated pages of my pocket ledger. It was just shy of full. A self that is its own antidote—there’s something to be hellaciously proud of. The cheap paper hissed with crinkly sibilance as I flipped to its cardboard backing. With that, I was gone.