During the first few minutes of the screening, someone behind me whispered: “Is this for real?” It is one of my favorite questions, because it usually indicates that something interesting is taking place, or about to. Like all rhetorical questions, it is redundant—there is nothing that isn’t for real—and its primary semantic thread is measured incredulity: you are, for a second, destabilized, attempting to decide what is and isn’t scripted, performed or not performed, constructed or not constructed.

The film was a low-budget documentary screened as part of the Prelude festival of new theater in the fall of 2007, and its subject was David Levine’s Bauerntheater, or “farmer’s theater,” which had premiered in Germany earlier that spring. The film begins with an image of the stage: a large, fallow field, located near a farming village just outside Berlin. We see an actor being hired—David Barlow. A script is rehearsed—Heiner Müller’s play Die Umsiedlerin—but we soon learn that not a word of it will be used, save for the name of a single character, a potato farmer named Flint. We see rehearsals in a warehouse in Brooklyn. Barlow/Flint stomps around inside a large, shoddily constructed trough filled with three hundred pounds of dirt in order to practice, again and again, the gesture of plowing and planting potatoes. Serious attention is paid to proper dress, and correct planting technique. Later, we see the actor being flown to Berlin for the performance. He arrives on the field, the stage. He goes into character, and the performance begins: for the next thirty days, for ten hours a day, five days a week, he plants the field.

Is this for real? Is it acting if you have no lines, no theater, no stage, no ushers? “Is it still ‘acting,’” Levine asks in his introduction to the Bauerntheater catalog, “if you’re doing manual labor? Is it manual labor if you’re ‘acting’?” And finally: “What does it mean to spend more hours of a day as someone other than yourself?” Much of Levine’s work interrogates conceptual terrains to a point where they momentarily annex each other. Labor isn’t just foregrounded. It’s literalized so that it becomes a metaphor for just about everything we do: rising out of bed, brushing our teeth, going to work, or, if you’re a beginning artist, sending out your work to galleries, magazines, cultural institutions.

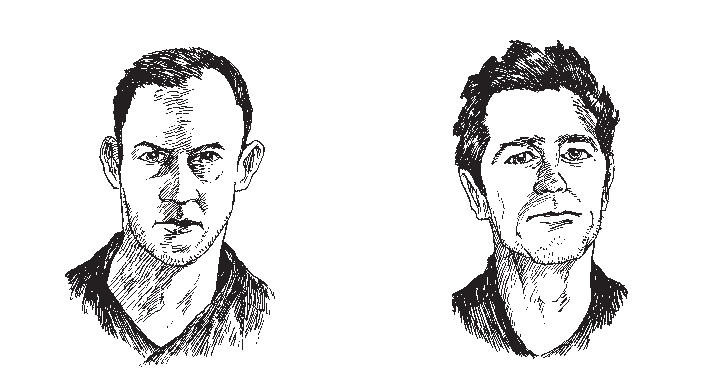

In July the Berlin gallery Feinkost will premiere Levine’s Hopefuls—an exhibition of Levine’s ongoing attempt to salvage discarded unsolicited actors’ head shots and cover letters—and this exhibit will travel in the fall to Cabinet magazine’s Brooklyn project space. An upcoming piece, Venise Sauvée (opening in...

You have reached your article limit

Sign up for a digital subscription and continue reading all new issues, plus our entire archives, for just $1.50/month.

Already a subscriber? Sign in