Tim’s Vermeer—Vermeer’s Music Lesson—Marker’s La Jetée

This being the film issue and all, I thought I’d try my hand at a piece about arguably the greatest filmmaker of all time—great-grandfather, at any rate, to all the rest of them—that being, of course, Johannes Vermeer of Delft.

The animating occasion for this meditation: the recent release of Tim’s Vermeer, the magician-skeptics Penn and Teller’s documentary film about their Texas-based inventor friend Tim Jenison and his remarkable experimental investigations into precisely how the seventeenth-century Dutch master might have been able to render all those astonishing paintings. And I should say at the outset that Jenison, for his part, comes off as a wonderfully ingenious and thoroughly congenial fellow. And who knows? He may even be right.

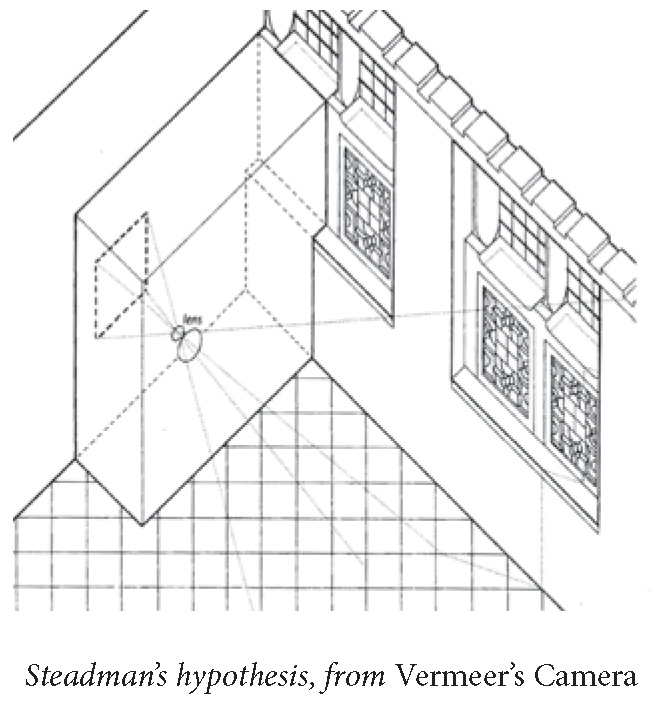

He’s hardly the first to have become convinced that Vermeer must have been using some sort of optical devices. David Hockney (who also shows up in the film) devoted many pages to the likelihood in his 2001 book, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters, and Hockney in turn frequently cited the meticulous investigations of Philip Steadman, who in his 2001 book, Vermeer’s Camera: Uncovering the Truth Behind the Masterpieces (and in subsequent BBC documentaries, also referenced in the Penn and Teller film), laid out the basis for his own conviction that Vermeer must have been using a camera obscura, which is to say an entire dark room, or at any rate a narrow closet, slotted off the side of his studio with a pinhole lens facing the scene before it.

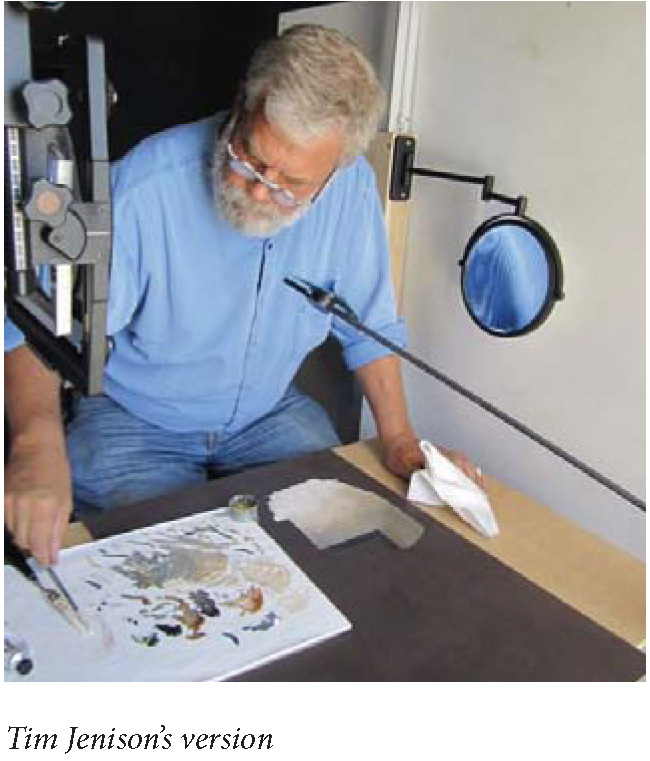

But Jenison does move this line of speculation considerably for-ward in several beguiling ways, notably by suggesting that Vermeer might have used a circular, flat mirror, maybe an inch or two in diameter and held out at a forty-five-degree angle from the tip of a stick mounted atop the horizontal canvas, so as to help him get the color details of the scene before him so precisely right (by gazing at the edge of the image reflected in the mirrored circle and then beyond that onto the patch of canvas being painted down below and mixing the pigments down there until the two images matched). Even more intriguingly, Jenison winds up arguing (based on months and months of trial-and-error efforts of his own) that Vermeer may not have had to use an entire dark room after all: rather, drawing on some of Hockney’s most suggestive intuitions, he demonstrates how a con-cave curved mirror affixed to the far wall, and focusing the image of the scene before it onto that flattened circular one, could have worked just as well, in fact substantially better, and could even have been deployed in broad daylight.

But beyond such inspired insights, at least in Penn and Teller’s telling of the tale, things take an ever more peculiar turn. For Jenison becomes the proverbial man obsessed, and Penn and Teller ever more uncritically entrammeled by his obsession, presently making claims for its results that Jenison himself might never have advanced on his own behalf.

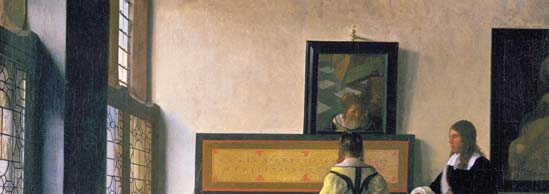

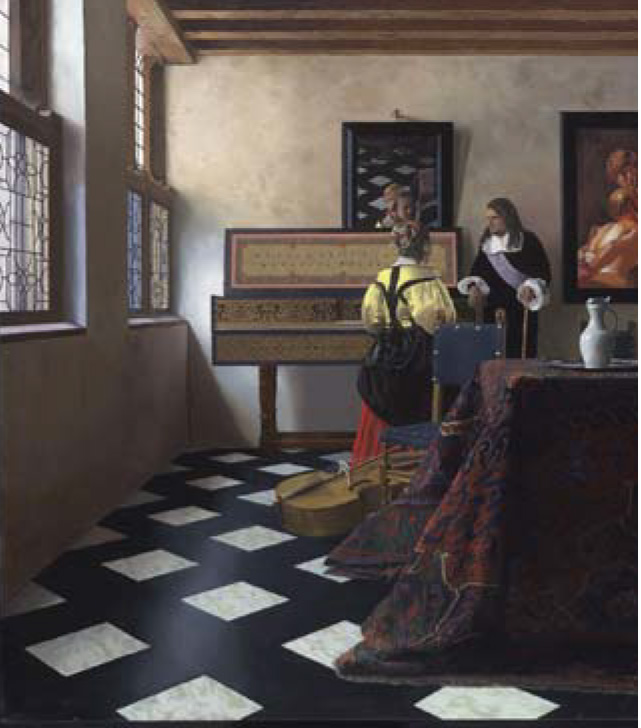

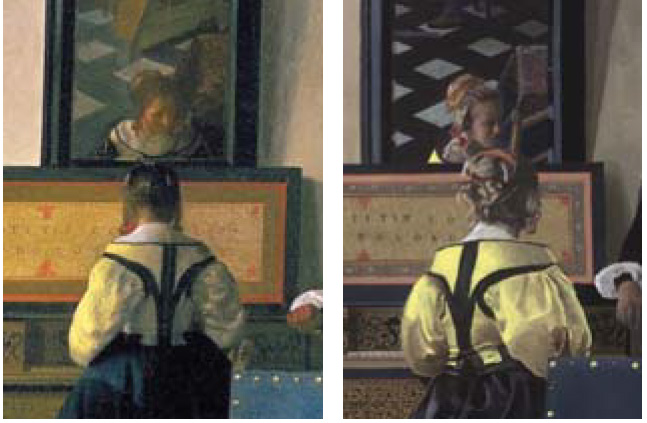

Jenison decides that he—a man with virtually no prior painterly training—wants to render a “Vermeer” of his own. There’s a kind of mad tautological folly to the whole ensuing endeavor as Jenison takes a favorite Vermeer painting, The Music Lesson (the very same canvas Steadman had focused upon), and then, inside his San Antonio studio hangar, contrives to project outward from the painting’s own evidence a full-size, three-dimensional version (complete with floor tiles, leaded windows, a white porcelain pitcher on a carpet-draped table, an ornate harpsichord, framed paintings on the wall, and two elaborately costumed stand-in mannequins) of what he believes Vermeer himself must have been facing as he undertook the painting. He then begins his own painstaking, painterly capture of the contrived scene—across hours and hours (and hours and hours), deploying all the optical devices he imagines Vermeer himself to have used (indeed, it is during this phase that he makes that second breakthrough of his, regarding the curved mirror)—and sure enough, the resultant painting ends up looking a whole lot like the Vermeer original. (As how, in principle, could it not?)

Which is fine as far as it goes, except that Penn in his voice-over and Teller through his directorial prod-dings now begin pushing things well beyond that. Enthralled by the single-mindedness of Jenison’s process—and in no small measure reverting to the gleefully smart-alecky disdain for all established authority, which is their notorious default style—they start implying, first, that Jenison’s painting is every bit the equal of the Vermeer, and, furthermore, that since  Jenison is a rank amateur with no prior painterly experience, given the right optical devices and the requisite gumption, pretty much anybody could do it—the sort of claim that Hockney, for his part, never came close to making.

Jenison is a rank amateur with no prior painterly experience, given the right optical devices and the requisite gumption, pretty much anybody could do it—the sort of claim that Hockney, for his part, never came close to making.

And yet, of course, Jenison’s “Vermeer” (which he ends up hanging with eminently justifiable pride of place at home, on the wall opposite his bed) looks nothing like the original, really. Or rather, what it looks exactly like is what a crisp, focus-perfect, modern-day photograph of the entire composed scene that formed the basis for the painting might have looked like back then and there in Vermeer’s original studio (if that was even how he worked, keeping all of the elements frozen in place like that for the months on end it took him to bring the final painting into being—which, alas, is pretty unlikely).

exactly like is what a crisp, focus-perfect, modern-day photograph of the entire composed scene that formed the basis for the painting might have looked like back then and there in Vermeer’s original studio (if that was even how he worked, keeping all of the elements frozen in place like that for the months on end it took him to bring the final painting into being—which, alas, is pretty unlikely).

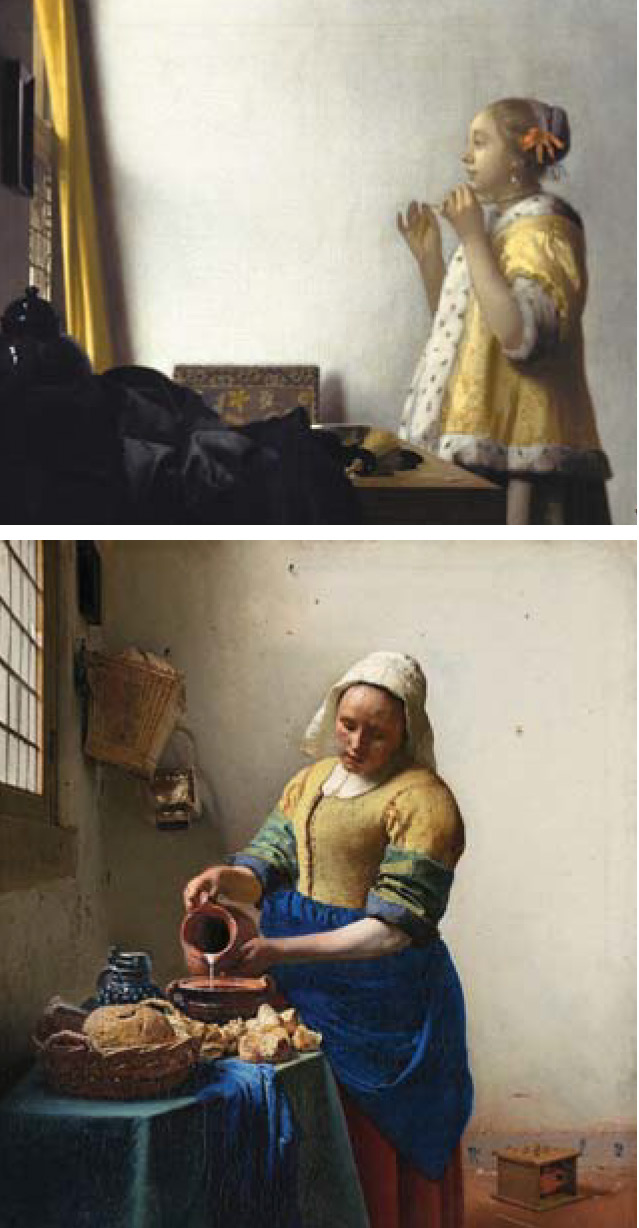

Consider the two canvases. Because the whole point is that Vermeer’s canvas doesn’t look like a conventional, modern-day photograph in any way: it is subtly out of focus throughout, everything softened ever so slightly from the optically exact, an effect that might, paradoxically, have been realizable only by using (or rather ever so slightly misusing) optical devices. The fact is that when we look at the world, everything we look at is in focus as we look at it, and it’s only by way of a projection of some sort that we are able to witness that focus of our attention out of focus. Time and again across his lifework (and virtually uniquely among the old masters), Vermeer delighted in recording the oddities afforded by such projections—the bubbles of light, the slight ambiguities, the way that, for example, in The Lacemaker, everything is out of focus (either too near or too far) except for the very thing the lace-maker herself is focusing upon—the V of stretched thread that forms the focus of her concentration.

Such exquisite oddities might in turn help explain the almost-total and otherwise-unaccountable eclipse in Vermeer’s reputation for almost two centuries after his death: he wasn’t rediscovered till the 1860s, which is to say in the wake of the invention and subsequent ubiquitous cultural proliferation of chemical photography (with—at the outset, anyway—its own distortions caused by the lens’s still-shallow depth of focus). Before this, Vermeer’s paintings probably looked “wrong,” whereas now they looked uncannily right and indeed more right than just about anyone else’s.

Beyond that, just look at the respective treatments of the central incident in the two canvases, Jenison’s and Vermeer’s.

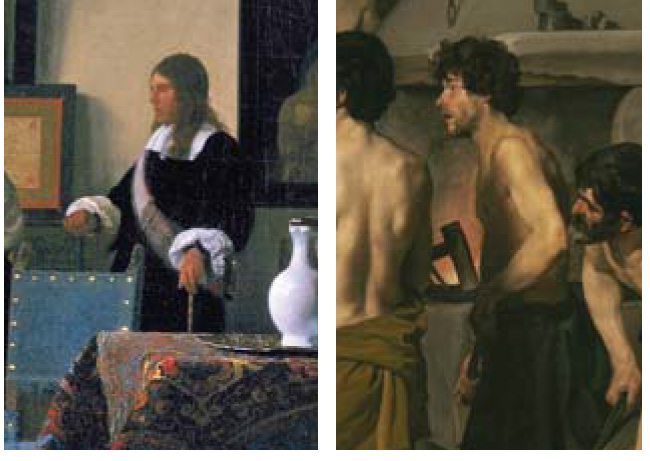

Since Jenison was confining himself to making an optically exact reproduction of the modeled scene before him, he had to choose whether to represent the woman as she appears “in life” or in the mirror hanging above the harpsichord, and in choosing the former, “corrected” Vermeer’s seeming mistake in making the mirror version pivot away from that of its real-life referent. But that pivot is the whole point of the picture. Jenison’s girl has stopped playing and is simply looking head-on at the man, who in turn is looking back at her head-on. It’s an entirely pedestrian moment: a conventional exchange of views. Vermeer’s girl, on the other hand, is still at her instrument, her eyes still on the keyboard, which she has been concentrating on playing, and may only just this moment have stopped playing—we can almost hear the last note sub-siding into silence—as, interrupting herself, she now begins (or so we can make out in the mirror) to pivot her gaze toward the man, who is hushed in astonishment, lost in his own reverie, a pillow of air, of in-held breath lodged in his mouth, taken by surprise, almost unprepared to return her shy glance. Compare, in this context, the look of Vermeer’s young man with that of the stunned youth upon the god’s epiphany in Velázquez’s Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan, from thirty years earlier.

Or make up your own story. (Alternatively, did he just interrupt her with some instructive admonition and now she is turning toward him in flustered confusion?) It’s magic—Vermeer’s scene allows multitudes—and that magic is the magic of cinema. Time and again, Vermeer does this sort of thing. For almost the first time in the history of painting, we have a painter consciously injecting duration into his canvases, the time of time passing. Others before him have of course portrayed people frozen in stillness, but that is because those people were posing: they’d been told to keep still, and there is an inevitable stiffness to the result (as in the early days of chemical photography). Vermeer often chooses instead to portray his women in the midst of doing things (pouring milk out of a pitcher, focusing on a V of thread, holding up a string of pearls, testing a set of scales), albeit things that force them momentarily to stand  still in the midst of time as it passes: again, we are witnessing a movie.

still in the midst of time as it passes: again, we are witnessing a movie.

Or else, as in Girl with a Pearl Earring (this having been Edward Snow’s thrilling insight in his A Study of Vermeer), the girl has just turned toward us and—one beat, two beats, three beats—is already starting to turn away, and both the turning toward and that imminent turning away are contained in the time of the picture—a sense of duration that in turn achingly implicates the rest of us: likewise frozen in place, Actaeon-like, we become hap-less voyeurs (the sort of thing that happens with—that feels like—real life across the passage of time, precisely as opposed to what it feels like to look at a mere photographic still shot—or at a Jenison).

Vermeer is the poet of absorption: the women are in themselves; we are in them. (This, precisely, as opposed to obsession.) And this in turn is where the slight lack of focus comes in. For that softness stands in, as it were, for memory. What we are invited to experience before one of these Vermeers is not so much things happening, or even just things happened upon and beheld, but rather the lingering hold that certain moments, once happened upon and beheld, continue, tollingly, to exert over us.

All of which is why if you want to see a truly great film about Vermeer—a film by someone who truly got him and in fact seemed at long last to be able to return his gaze, as if through a time-mirror, centuries after the fact—forget about Penn and Teller and Jenison and even Hockney with his speculations. Go instead to Chris Marker; go to La jetée.

All of which is why if you want to see a truly great film about Vermeer—a film by someone who truly got him and in fact seemed at long last to be able to return his gaze, as if through a time-mirror, centuries after the fact—forget about Penn and Teller and Jenison and even Hockney with his speculations. Go instead to Chris Marker; go to La jetée.

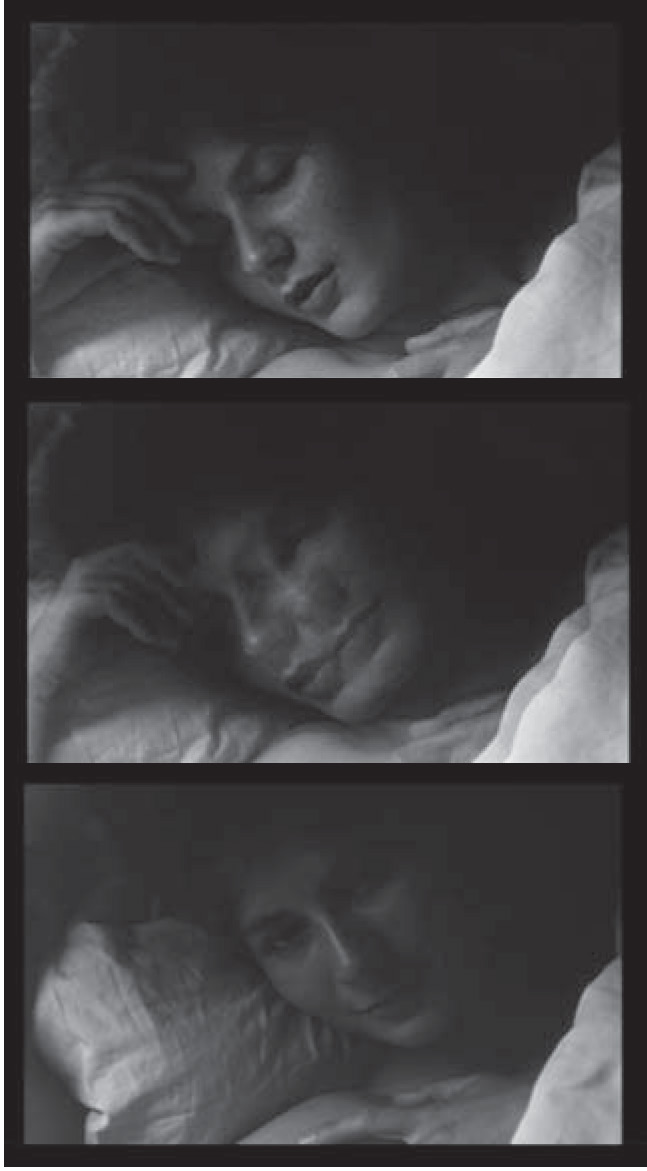

Marker’s 1962 short film (only twenty-eight minutes long and yet one of the towering triumphs of the French New Wave, if not of all cinema) relates an ordinary Möbius time-travel tale (one that was to launch a thousand imitations) by way of a hypnotic voice-over spread across a meticulously cadenced sequence of still images: one black-and-white photograph after another after another, and nothing but still photo-graphs, except for

one almost-instantaneous moving-picture sequence in which the beloved object of regard, a woman asleep in bed (the camera wedged close in on her shoulders and face), rolls over, momentarily opens her eyes, and blinks, twice.

After which the heartbeat pulse of still images resumes. The effect is almost subliminal: you may not even be sure it happened, but it is completely devastating and devastatingly memorable.