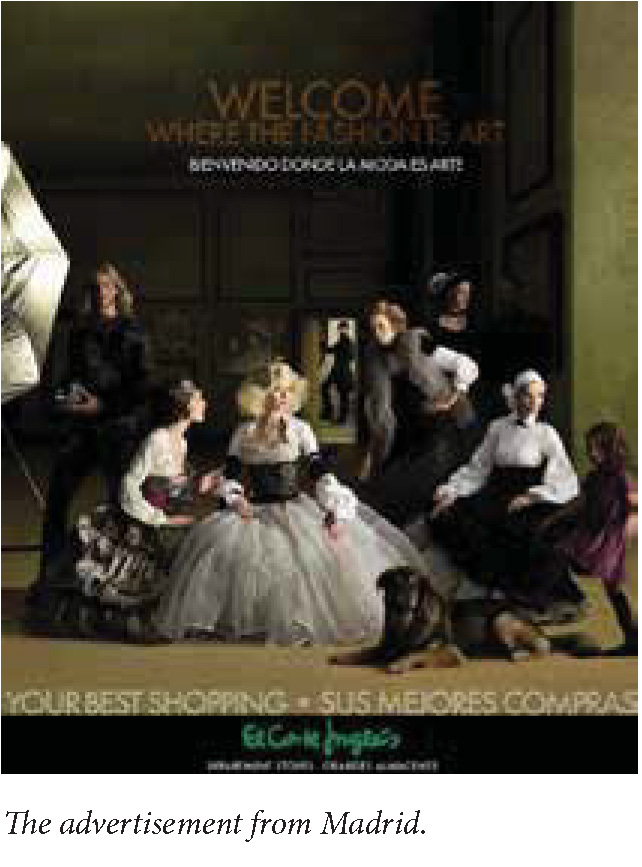

Take a look at this entirely captivating department-store ad, ubiquitous a few seasons back on the streets of Madrid, a sly pastiche riff on one of the city’s other premier attractions, arguably the greatest masterpiece in Madrid’s greatest museum, the Prado—Velázquez’s career-defining masterpiece of 1656, Las Meninas.

It’s an interesting thing about pastiches, because, as often happens with the genre, the copy helps reveal some of the deeper splendors couched in the original. Note how, in the ad, a photographer-dandy stands in at the same spot occupied by the painter in the painting, gazing intently, along with the rest of his crew of costumed models, into his own reflection in a wide facing mirror, it would seem, camera at his waist, getting set to snap the very image we now see before us—maybe even doing so at this very instant, with the image in the ad being the result.

For that matter, such, at first blush, appears to be the narrative conceit behind the Velázquez painting as well—but in the case of the painting, things quickly become more complicated.

For one thing, if that silvered rectangle behind and to the painter’s left in fact contains, as it appears to, a mirrored reflection of the king and queen, then maybe we are being invited to inhabit their point of view as they stand for their own portrait, with the rest of the courtly retinue gazing upon them (maybe the mirror is reflecting not them so much as the big painting of them the painter is in the midst of conjuring into being as he gazes upon them); or maybe it’s just that the royal couple happens to have happened upon the court painter busily in the act of rendering a group portrait of their daughter, the Infanta, flanked by her variously attentive retinue, hence their reflection in the distant mirror and the painter’s momentarily having been pulled out from behind his canvas to acknowledge their presence. Or maybe everybody in the painting is looking at a huge painting of the royal couple, leaning against the wall behind where we as viewers would be standing, and that’s what’s being reflected in the distant mirror.

But, looking more closely, none of those can be quite right. For one thing, the reflective optics don’t quite align; indeed, maybe that silvered rectangle in the background isn’t even a mirror at all but rather an earlier painting of the royal couple. (I mean, obviously it is a painting of the royal couple, a localized slather of pigmented muds spread over a portion of the wider canvas, but whether it’s meant also to represent a painting within the painting is a different question.) The fiction of the painting further seems to imply that, like the photographer, what the painter is looking into is a mirrored reflection of the scene before him, which he is in the process of rendering onto that huge canvas angled over to our left side of the painting, a canvas that, come to think of it, would in that case be the very painting we are now looking at.

But hang on, nor can that be right. Because that’s not how painting works. One of the important ways in which painting is different from chemical photography—which, remember, didn’t exist during Velázquez’s time, even notionally—is that painting is precisely not the world apprehended in an instantaneous blink. As he painted Las Meninas, Velázquez would have been standing more or less where we as viewers now stand (as we look at his painting), and, more to the point, the scene before us would at no moment have been a scene before him. Rather, during the months and months of the painting’s composition, Velázquez might have spent a few days working on the dog, and then another few days laying in the kid to the dog’s side, the boy teasing the endlessly put-upon dog with that little kick (and during those days, the kid would doubtless have been leaning on some sort of footstool and not onto the dog’s flank; if nothing else, the actual dog would not actually have sat endlessly still for such tomfoolery). A whole other sequence of days would have been given over to portraying the Infanta’s dwarf, and I doubt the Infanta would have stood still for that. And so forth. Furthermore, anyone viewing the finished picture would have known that that’s how it was made, and hence known how to read it: as a composition unfurling across time. It’s only we, living in the wake of the invention and subsequent rampant spread of photography, who are saddled with the fantasy of the immediate, the very fantasy incarnated in that pastiche department-store ad.

I’m hardly the first person to have become entrammeled by the enigmatic vantages embodied in Velázquez’s masterpiece.

Consider, for example, Foucault’s famous treatment of some of these same perplexities near the out-set of his 1966 Les mots et les choses, subsequently translated as The Order of Things—how he locates in Velázquez’s confounding image the very moment when the classical gaze (with its simple-hearted representation of “a window upon the world”) starts to question itself, everything becoming riddled with doubts and second thoughts, nothing anymore to be taken for granted: the upsurge, in short, of the modern.

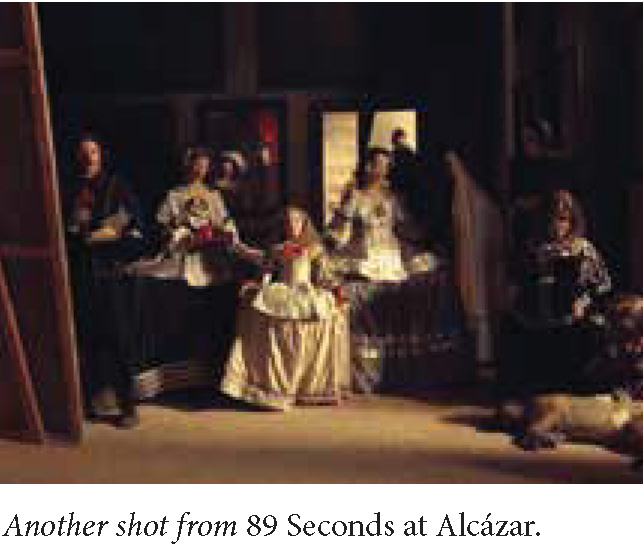

Or, more recently, British-born American artist Eve Sussman’s marvelous 2004 art-film fantasy, the beautifully flowing single-take ten-minute repeating loop enigmatically entitled 89 Seconds at Alcázar, in which elaborately costumed, vaguely (naggingly) familiar seventeenth-century-style courtiers and hangers-oncaper and flit about a large, gloomy, hangerlike space—children and a dog, an elegant painter and the clownish dwarf (and, wait a second, damn if that isn’t Peter Dinklage avant le  Lannister!), nuns and nursemaids and royals—until suddenly the whole thing snaps momentarily into place as that very Meninas image, and already everything is coming all undone, the dog plodding away, the children chasing after the dog, the nursemaids chasing after the children—like herding cats, we find our-selves thinking—all of which combine to suggest… what, exactly?

Lannister!), nuns and nursemaids and royals—until suddenly the whole thing snaps momentarily into place as that very Meninas image, and already everything is coming all undone, the dog plodding away, the children chasing after the dog, the nursemaids chasing after the children—like herding cats, we find our-selves thinking—all of which combine to suggest… what, exactly?

That that’s how it must have been, Velázquez just happening to have glimpsed that brief fleet-flitting decisive moment as the inspiration for his entire canvas, how thank goodness he had a Polaroid camera at the ready, tucked away in the ruffles of his cape, such that this, too, couldn’t have been at all like what actually happened.

See what I mean about the vertiginous opportunities for reflection, and reflections upon reflection, afforded by pastiche?

The same sort of reflections, at any rate, arise out of a consideration of contemporary photographer David LaChappelle’s recent pastiche tribute to seventeenth-century Dutch floral paintings. (Almost impossible to tell them apart, except note the gleaming cordless phones at the bottom of LaChappelle’s rendering.)

Now, LaChappelle had to gather flowers at various stages of decomposition, all of them bunched together and appropriately ruffled and bedewed with studious precision, all of them laid out just so, and now wait a minute, just one more adjustment—OK, there, right: now!—for his instantaneous photo shot. That is, unless—as nowadays is becoming more and more often the case—he Photoshopped the final image, layering in one flower one day and another the next, in which case he would have been engaged in an activity much closer to that of his seventeenth-century predecessor. (David Hockney has lately been commenting on the fact that, what with the rampant recent spread of Photoshop, for the first time since 1839 the hand of the photographer is reentering the frame and the often quite gaping 150-year divide separating painting and photography is thus rapidly beginning to close back up.)

The point at any rate is that during the seventeenth century, painters never actually attempted to portray fully brimming floral arrangements along the lines of the one ultimately offered forth in their finished painting (such an actual bouquet would long have wilted to compost before they could have finished their painting).Rather, like Velázquez, they slowly built up their burgeoning still lifes one blossom, one bulb, one branch at a time, all the while layering in ever-deeper significations (all those creepy crawlers and flitting flyers, for more on which see Harry Berger Jr.’s revelatory 2012 monograph,

Caterpillage: Reflections on Seventeenth-Century Dutch Still Life Painting, wherein the good professor suggests that contrary to their placid pastoral reputations, such paintings may afford some of the most violently roiling depictions and occasions for meditation on such mortal violence that any visitor nowadays is likely to encounter during his museum walk).

So I’m glad we sorted all of that out. On the other hand, when I happened to be lecturing on some of this stuff at the Spencer Museum of Art, at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, a few weeks back, Stephen Goddard, one of my hosts and the museum’s keeper of works on paper, turned unusually drop-jawed as I projected a slide of LaChappelle’s 2012 still life with cordless phones. Talk about pillows of air! I mean, I know it’s an uncanny image and all, but it’s not that uncanny. Afterward, how-ever, Goddard, an amateur photographer himself, pulled me aside and escorted me to his back office, where, revving up his computer, he proceeded to draw up an image of his own, a still life he himself had contrived back in 2008: He told me he had never publicly shown it. And, really, I don’t know what the hell to make of that.